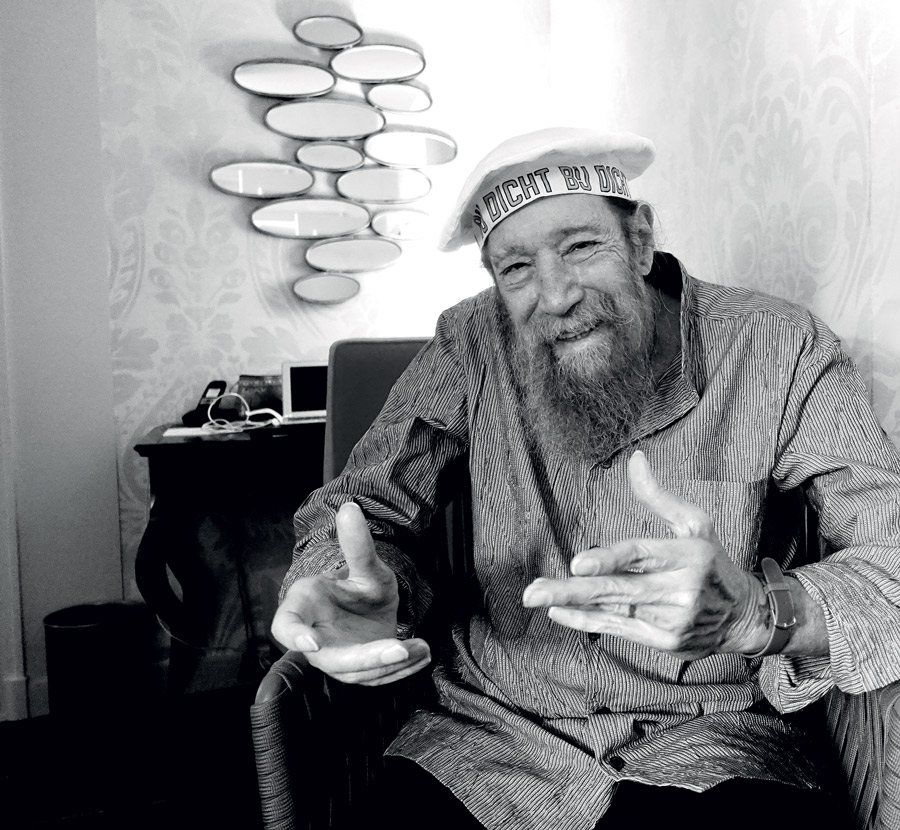

Photo by Frank Perrin.

A MEETING BETWEEN DAN GRAHAM & FRANK PERRIN

By Frank Perrin

Exploring the relationship between private and public space, interior and exterior, functionality and aesthetics, American artist Dan Graham has created works spanning a range of media – installations, videos, sculptures, photographs – that question our relationship to architecture since the 1960s. A diehard rock fan, he began his career as a music critic, before making his first artworks on paper – like Homes for America, a kind of report that lies midway between journalism and sociology. His famous “pavilions” – metal and glass structures in undulating shapes – arrived in the late 1970s, offering an unprecedented sensory experience that invites viewers to see themselves in the works and admire a not so distorted a reflection of reality.

Frank Perrin: Twenty-five years ago, Armelle and I published your text Punk Political Pop in our magazine Blocnotes.

Dan Graham: It seems that the biggest interest in France is not my connection with punk, but my connection with Kim Gordon! I was asked to do a lecture and there was only one question: “Is it true you had an affair with Kim Gordon?”

We’re very happy to have you back in Paris for a new show at Marian Goodman Gallery. The title of your new pavilion is Neo-Baroque Walkway. The Baroque is a very surprising influence for you. What could you say about this link with the Baroque?

First of all, I kind of discovered how important John Chamberlain’s work was for me and also for Donald Judd. We both wrote about Chamberlain’s work. Chamberlain and I are both Aries, and I’ve written a text about his great conceptual art. I also love the piece he did for a show at the Guggenheim, where he put couches in the lobby of Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture and you could look down and see people almost in a drugged state. Some people identify my work as having to do with memoir, especially with Homes for America. But that work really comes out of Judd’s writings. Judd wrote an article about the neoclassical city plans in Kansas City. And then he moved to New Jersey, which has a highway culture. That’s why his favorite artist was De Chirico and his paintings of the city plan of Torino.

This link between the suburbs and De Chirico is fantastic.

I think Judd’s greatest work was his writings. The first thing he wrote about Chamberlain was that his work is about built-in obsolescence, which also was the basis of Homes for America. But then he said Chamberlain’s work has the structure of the Baroque. There’s an Irishman who buys and sells hotels, in southern France, and mixes the entrances with a kind of fake rococo and baroque. It’s maybe just as silly as Detroit’s 1950s cars being fake elegant. Originally, this piece I did here was a proposal for one of those entrances. He also has a sculpture park. Sculpture parks are where my work usually winds up. I always say they work best as a fun house for children and a photo opportunity for parents. I kind of miss being in those very large shows like Documenta or the Venice Biennale that attract huge family groups. I also have seen some of the worst baroque architecture ever in Salzburg, so sometimes I like to take some of the worst to make something else of it.

A good dialectic.

Also, you see the piece in this room of the gallery: The Skateboard Pavilion. It was originally done for a show called International Garden Year, which happens every three years in Germany in Magdeburg. The city has a central park redesigned by young architects, and artists do works of art for their meetings points. This was one of my meeting points. I thought the pyramid in the center of these cities was somewhat a fascist symbol of power, and also used for corporate architecture. Skate parks were never done in city parks, so I thought if you went up in the air, it would be like a kaleidoscopic feeling inside a fascist monument. A lot of my work is about historical overlays. In that I feel very close to Isamu Noguchi, because I don’t understand what modernism is. It seems like some kind of empty word. The idea of the walkway or museum entrance is an ideal situation. The work I’m finally going to realize for the Whitney, called Portal, should have been the entrance for Documenta, but I’ll never be in these shows anymore. These entrances into European structures and condemnations of how awful baroque churches can be is maybe why I called this “neo-baroque”. I like the idea of pitching my work by saying it’s a fun house for children and photo opportunity for parents. I hate Rem Koolhaas’s architecture, but his first book about Coney Island was very inspirational. Like a piece I did for the roof of the Dia Foundation, Rooftop Urban Park Project/Two Way Mirror Cylinder Inside Cube, ƒthis is the idea of what happens in bad sculpture parks or even city parks. A lot of my work was very similar to George Seurat’s The Circus. The circus is a working-class form of entertainment, where people look at the spectacle and they also look at each other looking. And the reason I love Paris and New York is that I love to watch tourists, either looking at other people or looking at me looking at tourists. The other interest in this piece is that it works very well outside, because the sun constantly changes what happens. It also changes as you walk around it. And I just realized this work would work better outside than it does inside.

I also wanted to know about the film downstairs, since your Céline collaboration with Phoebe Philo presents another structure, produced for her fashion show in 2017. What kind of experience did you want to bring to the audience with this structure?

First I have to say, for my latest show in France, I did a piece for an alternative space in Marseille called MAMO (Marseille Modulor) which was located on the rooftop of La Cité Radieuse of Le Corbusier. The piece was called Tight Squeeze and it had an undulating sea pattern repeating and cascading against the sunset and Le Corbusier’s forms. When I was asked to do a runway, I basically ripped myself off. It’s the same piece, but I was very happy there were columns. Artists love galleries that have columns. We hate these antiseptic rectilinear cubes. So the fact that there were columns helped. It was done instantaneously, but I was kind of thrilled. Actually, it was a great temporary situation. As to how it worked, I don’t know. I was very seriously ill in the hospital, so I was not there. I was surprised to see it was actually on the internet. I have to say a lot of my best ideas come from fashion second hand. My work for magazine pages came from the ideas of paper dresses, which I read about in Time magazine by the way. Also, I almost did a staircase for a Dior men’s fashion store here, but it didn’t work out because there was a big column I couldn’t work with. I was very thrilled to meet Hedi Slimane, and he did an absolutely great photograph of me. I’ve realized a lot of ideas picked up by almost everybody in the general public come from fashion. In my neighborhood in New York, there’s a place called Resurrection, which has original fashion pieces from factories, like a museum. I would really like to go there, since I guess my hero is André Courrèges. I just like to participate in things I never thought I’d participate in. And also, I think people liked it on the internet, so I thought it would draw a nice parallel to have it downstairs. But most people can see it anyway on YouTube. A documentary was made about me by The Louisiana Museum in Denmark, where I start talking about childhood influences. But it also has a good image of my work at the MAMO, and there is a connection with children which I mention. My mother was studying educational psychology, and I remember as a child I was frightened of playgrounds and even other children. (laughs) But I also go back to the late 1940s. At that time, America believed in communitarian socialism, which we exported to a great architect Itsuko Hasegawa in Japan, whose work I admire a lot. I think at that period of time, Aldo van Eyck, the Dutch architect, and also Noguchi designed playgrounds in the United States. Somehow, I’m sliding into that aspect of urbanism from that time period. I’m also very astonished when I see these pieces, because I guess I’m kind of a child spectator looking at it. I’d like to do semi-collaborative work with architects or people who design parks. I guess all these exhibitions I’m in with terrible architects and pretentious things is actually a good situation. I don’t know if it would be better or not, but it will be discovered. I’m actually happy with the piece. This could be like astrological fascism, but Chamberlain was an Aries like I am. I was very close to Sol LeWitt and Sol was afraid of him, because we got drunk and apparently Chamberlain attacked Sol. But if you go to Marfa, Judd idolized Chamberlain. I think every work he did was a new idea. So at times there may be great intelligence disguised underneath what people misunderstand as an artist’s trademark. It was actually Lawrence Weiner, who was a great friend of Chamberlain’s, who kind of got him into Chamberlain.

Lawrence is a genius. The last interview I did with an artist was with him in his hotel for a show last December. I love him.

I also like the idea of things that are like stage sets. To go back to the runway, in a way that’s a stage set for a show. I don’t do theater, but I’m aware that there are great people doing theatrical things, like Robert Wilson. I also see my pieces often in sculpture gardens, so I think I was very lucky to do this runway show.

How does a fashion show fit into your work? Some are moving and mechanical, while others are seated and stationary. It’s a very interesting situation.

Well, I can give you a good example. There’s a small article I wrote many years ago. Andy Warhol did this film of people in bleachers watching a play. The idea is you look back and look at people looking. I know among young artists there’s a real interest again in performance. I would also look back to a period in America that people have forgotten, when people were doing theatrical things, like the Wooster Group. I know the Tony Oursler work now is inspired by Soap Theatre. These are things that impressed me and that I forgot about, but I make use of in some ways. I would say I’m an opportunist. The opportunity came around and I just decided very quickly. I don’t even know if it worked, because I wasn’t there. I have my other great heroes: Ray Davies from the Kinks, the Yardbirds… The music being done now is kind of a synthetic copy of some of the greats. But I can see how it actually works in terms of fashion presentation. So as much as I hate the music, I kind of love listening to it. There are a lot of coffee places around New York. There’s a place called Grumpy’s, where the baristas play the music they like. One woman put some folkloric music about troubled emotional situations. I asked her if that was from her teenage period, and she said: “No, it continues”. I don’t really understand what young people are listening to in music. It seems to be not as pure or as basic. But maybe it’s the unbasicness of fashion music that does the job.

In your film Rock My Religion, you show how rock’n’roll is a kind of new rising religion. Don’t you think nowadays that fashion is the new religion? The times have changed. What do you think?

I always looked at things from an anthropological point of view, not a sociological one. First of all, I’ve always been a feminist. The works of Margaret Mead were available for me to look at as a child. I also grew up in a period in America where Eleanor Roosevelt was my mother’s idol. Instead of writing about rock music or doing work that related to feminism, I wanted to discover a feminist heroin for a film. I never really liked Patti Smith’s music that much, but Thurston Moore had the keys to my place. I had the keys to his place downstairs, and he had files on Patti Smith. I ransacked his files and Patti Smith’s fanzine had a lot of personal information in there. I created a kind of character and I thought maybe rock was her religion. Also, it was before anybody talked about sampling. With a cheap video camera, I was able to document early hardcore. And I noticed there was a huddle situation in hardcore that was a lot like American football. Which is very similar to what Simone Forti was doing in her film called Huddle. I was always interested in the idea of male bonding. I was also interested in Shaker history. For the film, I went up to Manchester which is where the industrial revolution began. I was able to document the industrial site there. And guess who’s from Manchester? A great hero of mine at that time, Mark E. Smith from The Fall. The film is what I could have written as an article. When I did it, I was deeply depressed, but I remember I really wanted to finish it. So I took a Greyhound bus to a place near the Shaker Village, and I think I walked about thirty miles and videotaped it. I used very cheap editing equipment – I never thought it would survive. I also think it was so Protestant that when I showed it in Catholic countries like France, I thought nobody could possibly like it. I’m surprised it somewhat endured. When I got into art, all the artists were writers. Andy Warhol was a great writer, although he was dyslexic. He may have wanted to be a writer. I wanted to be a writer. I read Walter Benjamin and Lizzie Fielder, an American literary critic, and a lot of French novels. Rock My Religion is a kind of rock’n’roll criticism of music during a certain time period. The next video I showed, the Rock’n’roll Puppet Show “Don’t Trust Anyone Over Thirty” is actually a period piece. It’s set in 1970, because that’s the year the hippies moved to the country, and the year of the first Neil Young album, which has my favorite song. And my favorite group, The Seeds, are featured. The idea to do a puppet show – I think Rita Ackermann has similar ideas – was I thought grandparents and older parents could take their children to see what it was like during that particular moment in hippie history. In terms of my being a hippie, artists at that time were all fellow traveler hippies. It was their culture, but we observed the culture. We didn’t actually participate in it directly. I created composite characters like Neil Sky. By the way, it’s a copy of a film called London Streets, a Hollywood film for kids about a rock’n roll star who becomes president and lowers the voting age. He also puts people over thirty into concentration camps where they’re given LSD in the morning. Of course, I rewrote the script, but I thought I could get away with it because the people who wrote operas also ripped off popular narratives. It exists not only as a video, but I brought it out as a book with a DVD published by Walther König. My puppets are doing very well, whereas my art pieces are unsellable lately. I think it’s because I don’t have a trademark.

I was thinking yesterday during the opening, while looking at your baroque corridor and the two vintage photos, you always do two pictures and two walls. You have a very meta structure with opposition and dualism. How do you see that?

I’m borderline schizophrenic. One of my favorite writers – Philip K. Dick – was, so, that’s a good position to be in. When I was a teenager going to school, I hated school, so I read Nausea by Sartre, as well as parts of Being and Nothingness. Maybe I learned an awful lot from that small section about the gaze as a child. I see Lacan as an academic hack. He also took a lot from my mother’s teacher, an educational and Gestalt psychologist. Also, from a feminist point of view, I guess men are voyeurs. With my father, I made a telescope out of a kit. I formed a telescope club where we’d take fellow students, including rather beautiful women I was very shy around, to the Princeton observatory. I also remember aiming a magnifying glass to kill ants. I then found out that’s not a male thing, women also do it. These kinds of things happen when you’re at a certain age, like twelve and a half, and maybe hate school. I describe myself as an anarchist. In Europe I had a great liking for French socialism and Norwegian socialism. I have to believe and non-believe in certain things. I don’t think artists work for an ideology like that. People do sociological critiques, but I don’t really trust that. It’s so academic. I’ve always been anti-academic.

Do you still find interesting things in underground culture?

I never thought any of these things were really revolutionary. I just like observing a culture and I’ve always loved media. I grew up with magazines and Homes for America was actually a parody of Esquire magazine, where they would have a sociologist saying terrible things about suburbia and have photographs of suburbia. In a way I was making fun of that. I remember there was one period in the art world where everybody wanted to get rid of the idea of economic value. Lichtenstein thought he could use printed matter as his value painting. My solution since I wasn’t really an artist and had no way of making art was to use a magazine page as something disposable. Side Effect/Common Drugs is based on “Mother’s Little Helper”, but also it was a way to make a Lichtenstein or Larry Poons and also be disposable. It had a lot to do with magazine pages themselves. For my piece Detumescence, I had advertised for a clinical medical writer and said write about what happens to the male after tumescence, and write it in clinical language. It was like making a hole inside the magazine. This was actually before what they call conceptual art. It had a lot to do with what I loved about magazines, the fact that they were disposable. I was also very influenced by what Rolling Stones did. I thought Side Effects/Common Drugs could be in a women’s magazine. My father used to read Ladies’ Home Journal and there was a column “Tell me doctor” that he read. (laughs) Of course that culture’s over right now. Everything I do has a lot to do with my age group. I’m realizing that artists my age are very interested in radio. I know Chris Williams is doing radio dramas. I think Jack Goldstein’s very great work had a lot to do with sound effects that were used for soap operas and radio. Mel Brooks’ first character was a 2000-year-old man which was a radio program. I listened to the radio in the bedroom, listening to disc jockeys away from the parents. I’m not looking for things that are underground, I’m just reflecting exactly my age group. I’m not necessarily influenced by other artists. But also I’ve discovered – since I believe in astrology – that I’m becoming more Capricorn. All my favorite artists are Capricorns. My favorite artists are from the nineteenth century: John Martin, Thomas Eakins. The interesting thing about John Martin is he began proto-cinema. He actually painted on glass and the French were very influenced actually by some of his early works. He also illustrated the first science fiction novel, Mary Shelley’s The Last Man. The work I’m interested in now are period pieces. A good example of a period piece movie is Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. It depicts exactly 1969 in LA and it also has a great soundtrack. The Sharon Tate character discovers Paul Revere & The Raiders’ new album. At the very end of the film, there’s also my favorite song from the Mamas and the Papas, “Twelve Thirty”. I remember the Mamas and the Papas started the song with, “I Used to Live in New York City”. In my latest greatest hits I put on a song from John Phillips (the Wolf King of L.A.), John Phillips’ first album, called “Holland Tunnel”, a story about a suburban commuter going through the Holland Tunnel to a boring job in NYC. He was a very strange character, John Phillips. At the end of his life, after the Mamas and the Papas dissolved, he sold drugs with his daughter on the Sunset Strip. They also lived together as a couple. I was turned on to that last album by Rodney Graham, he said it was a favorite album of his. So I guess my hobbies like rock music, which are shared by other artists, is the basis of my real interests. That’s also why I love Ed Ruscha. His photography is basically a hobby. Although I’ve never met him, I like his attitude toward art.

I would say your work is a language first of all, and Ed Ruscha’s work is also a language. More than form, it’s really a verb or language. There is a lot of connection.

One thing I have to say is that I learned a lot from Flavin. Dan Flavin and Sol LeWitt were guards at the Russian Constructivist show at MoMA. I’m interested in that hybrid of different areas. Finally, Flavin believed in homage. I think a lot of my work, and even Bruce Nauman’s work, is homage to other artists we admire. Somehow you don’t see that a lot in artists for art magazines, but I think it’s quite important. I also discovered something I hated: French impressionism is maybe more important to me than I thought. Sometimes things you hate become important.

Of course, that’s part of the process.

What I hate now is art being trademarked. That’s why I’m fairly unsuccessful. I think I’m very lucky to have a show here, and also to be working with Johanna, who’s an absolutely incredible producer. I think everybody needs a producer. I didn’t want to overload the show with too much, so maybe it works.

Is the notion of experimentation important in your work?

A lot of my work is a critique of the previous work I’ve done, which I think doesn’t work. I don’t know if that’s experimentation or not. I think things are hard to read because they’re hybrids. I think that comes out of Russian constructivism. The idea of literature being a part of it… When I came into art, I wasn’t an artist – I knew nothing about art. My dealer John Gibson decided I should do art, and I realized I could get air tickets and see the world. Everybody says my work is avant-garde, but I think it’s closer to a kind of hybrid. I think Judd wanted to be a writer and Flavin thought he was like James Joyce. He actually did a diary column for Artforum. Ed Ruscha was a chief layout designer for the first Artforum. I didn’t have any of those talents, but I think the idea of professionalism in art and trademark product – which I can see why a lot of artists went toward – are kind of traps. I also unfortunately have made a lot of enemies. I have a great dislike for Duchamp, mainly because I think he’s so typical of formality. I discovered how wonderful Courbet was when I had a show at the Met, and Duchamp was afraid of Courbet. I don’t understand why these critics make so much of him. Although he had great friends, so he must have been highly intelligent to pick such great friends. I shouldn’t mention his name, but I think Daniel Buren has really over simplified Flavin, and there’s no sense of humor there. In other words, he’s kind of a political animal. Also, when I was teaching in France, all the students seemed to have imbibed a Cartesian logic. They never wanted to talk about their emotions or personal memories. So I guess every area has its trap. The trap in Holland is also over-rationalization. But I’m lucky to have been a teacher in all these countries, so I can figure out what’s good and bad there.

Has it been a long time since you came to Paris?

The first time I was in Paris was when Ileana Sonnabend wanted to show me. I turned her down because I was very loyal to this little gallery in New York that sponsored me, the John Gibson gallery. Later I realized, Ileana really liked my work and she was a more important figure than I thought. But I wasn’t interested in any kind of success or becoming a well-known artist. The I showed with Galerie Durand-Dessert because my friend John Hilliard showed there.

I remember we have a friend in common, Roger Pailhas. Do you remember him and Jean-Louis Mauban? They produced the Children’s Pavilion.

Well, first of all, to be honest, the first Children’s Pavilion was Jeff Wall’s idea. The real idea for the Children’s Pavilion was because I was in a show called Chambre d’amis, curated by Jan Hoet in 1986, which was a brilliant show. Jeff Wall saw that and decided to do the Children’s Pavilion. I thought it was a fantasy. But over the years, I actually redid the architecture and it was almost done for the year 2000 in the city of Blois. But it was a fantasy situation to begin with. Jeff Wall by the way was a very good teacher. My very close friend Rodney Graham owes a lot to him as a teacher.

What is your personal background?

I grew up in a professional-class Jewish family, in a kind of army barracks area after World War II, and I feel very close to Catholic Italian-Americans and Polish-Americans. The high part of my life was meeting Ray Davies of the Kinks and having a conversation with him. Another high point was meeting great architects whom I admire and to share my architecture books and information with them, but not trying to be an architect myself. There are some good French writers. I think Roland Barthes is really genuine, and he was a real writer. I don’t like Foucault because I think he’s too sociologically reductive.

Do you like Deleuze?

I never read him. But I heard that Derrida was a very nice person and good to his students. Sol and I used to love Michel Butor, and Sol hated Robbe-Grillet because Judd liked Robbe-Grillet. I saw some of Robbe-Grillet’s films and the last film was about Delacroix. All that period was so important because everything was translated in Evergreen Review by Grove Press. I guess I picked up an awful lot from France, but I don’t believe in such a thing as French philosophy.

Dan Graham, Neo-Baroque Walkway, 2019

Two-way mirror, stainless steel, powder coated steelplates

90 1/2 x 272 7/8 x 95 1/4 in. (230 x 693 x 242 cm)

View of the exhibition, Dan Graham: New Work, Galerie Marian Goodman, Paris, 2019

Courtesy of the artiste and Marian Goodman Gallery

Photo credit: Rebecca Fanuele

Dan Graham, Skateboard Pavilion (1989),

two-way mirror, micro concrete and MD, aluminium, graffiti,

94x127x127 cm (detail)

Courtesy of the artist & Marian Goodman Gallery

Interview by Frank Perrin.