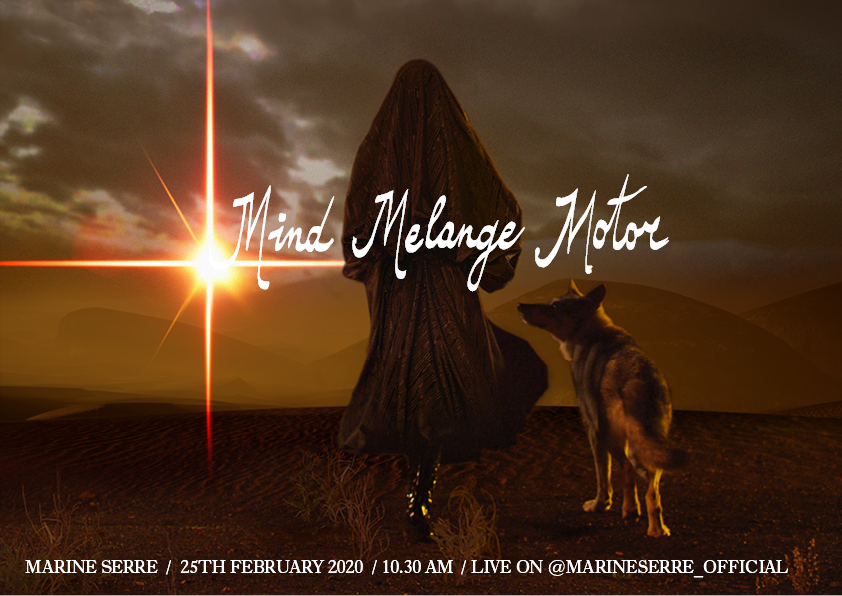

Marine Serre - Total look

A MEETING WITH MARINE SERRE

By Alice Butterlin

Fresh out of fashion school at La Cambre, French designer Marine Serre first made waves at the Hyères Festival, and then in Paris where she won the immensely competitive LVMH Prize. In just two years, Marine Serre pulled off the incredible feat of successfully launching her own eponymous brand. Her first catwalk show was a revelation, crystallizing a style that blends a futurist aesthetic with an incisive reflection on the future of consumption. At Marine Serre, eco-responsible productions methods are more than just the icing on the cake. The designer manages to join functionality and sophistication with attractive green fashion. From the outset, she has focused on upcycled garments as a crucial building block of her collections, as shown in dresses made from used scarves and sheets or handbags crafted from soccer balls. For Marine Serre, the revolution is here.

You won the LVMH Prize a year and a half ago. How did winning the award help you to advance your business?

Winning 300,000 euros in prize money when you weren’t expecting it changes everything. Looking back, it’s clear to me that I would not have accomplished so much so fast without it. From developing the Green Line to finding new methods of production, these are all things I was only able to think about after winning the prize. Without it, I would have had to wait till I had made enough sales to give me some investment capital. Prize money is like a shot of vitamin C or Red Bull for designers. (laughs) But you still have to know how to manage everything because things move so fast. There are a lot of positives, but also some issues that are hard to manage. When I won the prize, there were three of us managing the brand (my sister and my boyfriend), and I was living in a tiny studio. I had a bed and maybe one table. Everything changed in just a year and a half. Now we have twenty people working in a 1,300 square foot office. I knew what I wanted to do so I invested all the money into my business. I was determined to make it work. There were only six of us for the first show and I was still working for Balenciaga.

Have you found your groove now?

I’m getting there. But it’s definitely better than having two jobs. The toughest thing for a designer is to stay calm when you only have six months to make things perfect. You have to be pragmatic and make quick decisions. It’s even harder if you don’t know what you want to do. Once you have your idea, it’s just a lot of hard work, like any startup. I love my brand but I never expected to win the LVMH Prize.

How do you usually start working on a collection?

Well, I never do sketches. I have a small team who knows me well, so it’s easy for us to communicate. I have a lot of developers working on the Green Line and Red Line, since all the pieces are so difficult to put together. About 30% of the fabric is recycled. I also work with many different sourcers. I’ll tell them something like: “We need to find sheets like this”. And they get the job done! We also have a lot of production and development challenges because we work in such an unusual way. Factories are always puzzled when I ask them to make dresses out of used scarves. It’s a new process so they just have to trust us.

Your process ensures that every piece is unique. When using vintage fabrics, how do you make sure you will have enough material?

We buy everything before the show. But it’s true that there is always a risk of running short. We worked with scarves for the first show and we bought enough to make sure we could fill orders from showrooms. I remember we sold sixty or seventy pieces of a certain djellaba model, which is a lot because they sell for 2,500 euros each. It’s so nice to see people buying the collection. I’m interested in marketing items that are more affordable than couture, but still have a fine artisanal quality. All our recycled jeans are made from pants we recut and upcycle.

When did you get started with upcycling?

My school in Belgium had a big influence on me, as well as my internship at Margiela. When you don’t have a lot of money, you upcycle used materials. There’s something almost instinctual about it. For my fourth-year collection at school, I used old blankets and tarps to make trench coats. I had no idea at the time that it would turn into the Green Line. It was just a way of seeing things that came naturally to me. Every fabric ultimately works the same way, whether it is used for another purpose or not. I’m fortunate enough to have my own brand today and to be able to control so much more than just the silhouette. Just before the “Manic Soul Machine” collection, which we showed at Paris Fashion Week, I asked myself a lot of questions. Why was I there? Sure, I won the LVMH Prize, but there are so many other talented designers. I wanted to find out what could set me apart from the others, and what I wanted to build. These are very basic but also very complex questions because we have so little time today to ask ourselves what it is that we are doing and why we are doing it. I wanted to be honest with myself. Making radical choices has become the rule for my brand. I’m insistent on the fact that the Green Line is all upcycling and overstock. It’s not organic cotton or recycled materials. The Green Line is about clothes for the apocalypse. When we can no longer create new garments, we will be forced to salvage what we already have. Why would I wash more denim for a new pair of jeans when I already have twenty tons of jeans just sitting around?

It’s clear that upcycling is not just a gimmick for you, but a powerful way for you to imagine your collections.

I did a lot of thrifting when I was younger, so I have a soft spot for garments with a lot of history. I like pieces that endure; I’m not here to make trendy clothes. If I buy a washed denim jacket, I’d rather it be made from twenty-five pairs of old jeans. It lends extra value and cachet to the piece. Everyone wants to make green fashion, but it’ important to ask what that means.

Let’s talk about your time at La Cambre in Brussels. It’s a school that pushes students to design the wildest and most original pieces possible. Did you like that experimental approach to fashion?

Yes! I decided to study at La Cambre because the curriculum focused on working in 3D. I don’t like sketching clothes; I need to see the volume of the body. Even Stockman mannequins seem too rigid to me. I like to drape fabrics directly over a real body. Studying at La Cambre means five years of research. My graduation collection was so successful because I had spent seven years finding my style. I already understood my place in fashion when I started “Radical Call for Love”. At first, I didn’t feel comfortable saying that I worked in fashion. I told my friends I was a designer, but that could also mean designing chairs. I’ve always loved clothes and I kept a collection of exceptional pieces, but the fashion world intimidated me. Soon I realized that fashion is a medium of expression that I could use to convey a message. It’s not just about skirts. That realization opened my eyes and showed me that I didn’t have to follow the trends. During the first year at La Cambre, everyone learns how to make the most eccentric forms possible. They encourage students not to pay too much attention to what’s going on in fashion, so we can forge our own original vision. And the technique you learn there gives you absolute creative freedom. Brussels is also an eclectic city, apocalyptic even. (laughs) It’s not a fashion capital so we learn to make a different kind of fashion. And since La Cambre is an art school we are exposed to many other disciplines.

Groups and collectives are becoming more common in fashion and art. Working together has become a real asset. Did you see any groups forming while you were at school?

Yes, some of my friends formed groups. My brand came together so quickly after winning the LVMH Prize, and Marine Serre was not necessarily the name I wanted to give it. I just told them my name and then it was already written on the screen, even though it wasn’t even a brand yet. During my last show, a lot of my friends walked the runway, created prints for the jeans and took photos. I like including my friends in my work. It’s super important not to work alone. Designers never work alone; they are always influenced by the people around them. But there is a cult of personality surrounding designers and that means that one person is always in the spotlight. My sister helped me and my boyfriend still works with me every day. Everyone working with me today is part of my brand.

You chose a powerful symbol, the crescent moon, for your logo. From the beginning, you seem to have grasped the importance of logos in today’ world. What do you think about the wave of logomania that has swept over fashion shows?

I think it’s over. (laughs) Everyone needs to identify with something, and logos are clear and identifiable. It’s like belonging to a religion or being a vegan. You are what you are. Having a t-shirt with a certain logo can make you feel like you belong to a certain group or school of thought. I created the crescent moon print as part of the “Radical Call for Love” collection, and it was in reference to the attacks on November 13, 2015. But I decided to keep the logo for other reasons. It’s one of the world’s oldest symbols, as a symbol of a Greek goddess of femininity, so it doesn’t belong to me. It’s a symbol you find everywhere and it means something different depending on where you are. For example, in Japan it’s associated with Sailor Moon. It’s also similar to soccer jerseys and all their symbolism. There are some pieces where I didn’t include the logo, though not for any specific reason. There is a connection between religion, fashion and sports that is worth exploring. Logos are important in all these areas.

In your collections, you seem to have a firm grasp on how women live today, by offering very practical pieces with a lot of different compartments. Are you thinking about everyday life when you design your clothes?

Yes, and being a woman designing for women is certainly an asset when you’re trying to create wearable pieces. There is obviously a very practical and technical aspect to my clothes, which comes right from my own body. We try on all of our own pieces so we can see how they feel. Futurism is on everyone’s lips lately, and my slogan is “futurewear”. But there is a world of difference between the futurist aesthetic and actual garments designed for the future. I don’t make clothes inspired by science fiction; I think hard about how the composition of garments will evolve over time. For example, I need to take a bottle of water with me whenever I take the subway, so I built a special pocket for that purpose in the Survival Jacket, which also has a slot where you can keep your Navigo tap card. These are important details that make people want to buy the jacket. These are clothes we wear every day, so they have to be super practical.

How do you include an element of fantasy in such practical clothes?

As a young brand, it’s important for me to spend time on the finishing touches. We set our standards very high in that regard. It takes time to find the right lining or the best topstitching. It’s a challenge. At the time, I made the Survival Jacket because, as a woman, I didn’t like always having to carry a purse. I kept wondering what guys used as purse. (laughs) Where was their hidden pocket? (laughs) My designs often come from very basic ideas that end up creating my brand’s aesthetic.

How do you see catwalk shows evolving in the future?

I used an unusual casting process for the last show. We can also ask ourselves why we do catwalk shows. I think they’re important because it’s a chance to introduce your work to buyers, journalists and people who might support your work. I could always open a showroom or put photos online, but I’m not interested in that kind of thing. Catwalk shows provide a chance for a group of people with similar tastes to meet up and talk. It’s fascinating to see over six hundred people pack in to see a fifteen-minute show. If you were also asking if catwalk shows are still relevant, I would say they are. But you have to do something radical with them. I want people to have a fun and memorable experience. If you only see the show on a screen, you don’t get to feel all the energy and you forget everything very quickly.

Are you working on any especially interesting projects?

We’re working on the projects announced last season for the different lines: the red line, the green line and the white line. The red line consists in pieces made from dead stock and used or vintage pieces in a couture spirit. We want to continue with these lines and develop them as much as we can. We are also moving in to our new studios in April. We found a great space that will also allow us to produce some of the green line pieces in Paris. There is a ton of preliminary work we have to do before we create any fabrics or thread any needles. We get a lot of used jeans and scarves we have to sort, wash, fade and redye. It’s important for us to keep the entire design process under the same roof, so we can control every aspect directly and not lose our values. We’ll have all our employees with us in our new space. You mentioned groups before, and that’s where our brand is heading. From installation and graphic art to music, we want to bring everyone together. In the long term, we want to think of ourselves more as a factory than as a fashion house.

Marine Serre – total look

Marine Serre – total look

Marine Serre – total look

***

Photographer: Naguel Rivero

Stylist: Andrej Skok

Model: Anna P. @Tomorrow is Another Day

Make up: Yasuko Sudo

Hair: Akemi Kishida @Atomo Management

Photo assistant: Gabrielle Vigier

Stylist assistant: Aurelia Mamadou