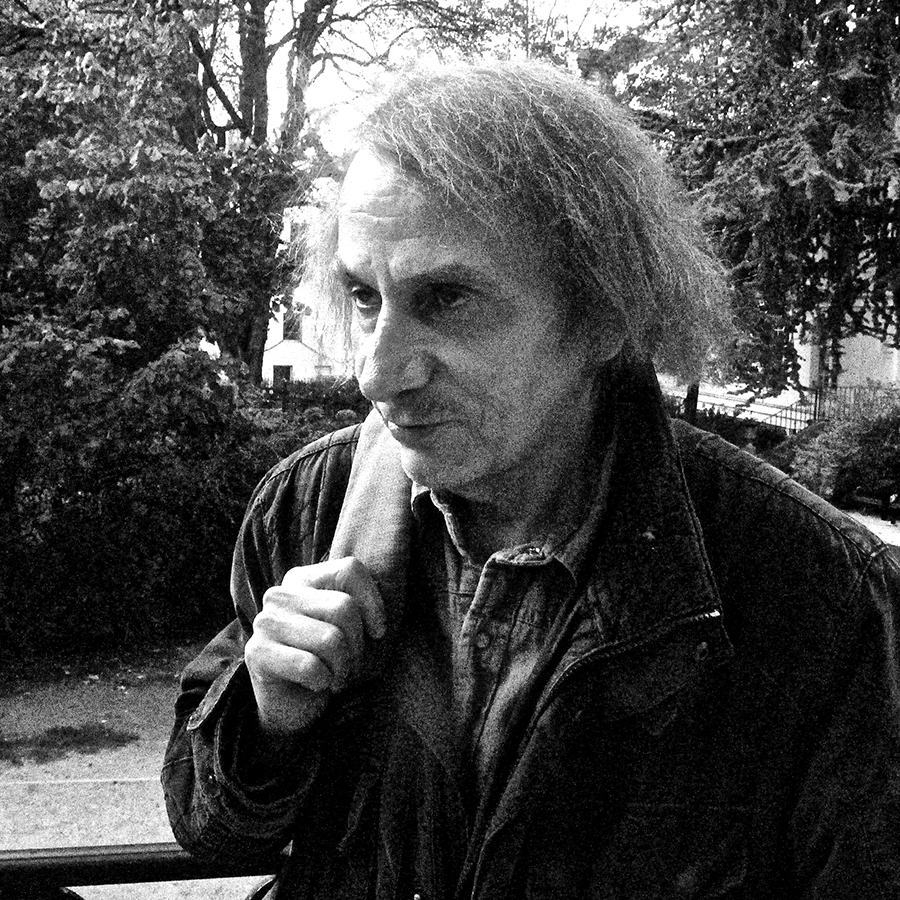

Photo by Quentin Hourie.

A MEETING WITH MICHEL BLAZY

By Lise Guéhenneux

Since graduating from the Beaux-Arts de Nice in the early 1990s, Michel Blazy has shown his work primarily at the gallery Art : Concept. Many are familiar with his work with plants and his use of materials seized from the flow of contemporary consumer life. By taking the notion of experimentation as a gateway into his practice, the artist moves beyond images to shed light on how he understands experimentation and the fertile grounds where it can emerge today.

How do you see the notion of experimentation in your practice?

It is tied to the nature of my work, which has been performative since the beginning, meaning that it happens during the exhibition. I do research work in the studio, but then I take the duration of the exhibition, the temperature of the space and its moisture level into account. I’m not going to show the same pieces in winter and summer. At the last FIAC, I showed the Buisson lentille piece, whose evolution is only visible over short periods of time of just a few hours.

Do you sometimes raise plants or objects in the outdoors part of your studio on Île Saint-Denis?

Some pieces are still living after the exhibition and so I keep them. The series of pieces made of rusty pipe sections with maples (sans titre) growing inside can live for a very long time if they are properly cared for: maple can live for over eight hundred years. Each room has its own lifespan. Then there are experiences that can be reproduced anytime, because the experience is the part that interests me: the time spent in the company of the work, watching it, taking care of it.

Do you conceive of this experiment “that can be reproduced” in an almost scientific way?

No, by repeating the experiment, I’m not trying to reproduce an identical form, nor do I try to control all the parameters of the experiment. At first, these are experiments I do in my studio under certain conditions, which I then transport to another biotope or situation. I watch as the experiments progress. I get to know the reactions of the piece in these different circumstances, as wel as its properties.

So your practice is based on this observation?

Yes, and this observation guides my actions, as I try to develop as much as possible what I have put in place, even though I do not fully understand it. Without knowing the reason why, I’ve worked to answer this question: “How can I use the minimum to make something that will stand up?”

Even when you work with inert materials?

Their shape also changes according to the number of visitors or humidity. The aluminum cube or the pieces with toilet paper (Mille feuilles) are made of only one material, without adding glue or anything else. They are attempts to understand the material, to produce a minimum gesture so that the material can organize itself. What I’m trying to do is provide support. An example that I often give and which still applies is that of the gardener, who provides support through simple actions but does not grow the plants from nothing.

A kind of caregiver?

The gardener is there to encourage things as much as possible, to try to understand them. I am fully a part of that relationship. I also believe that experiences work for us and give us shape. Anyone who buys one of my pieces does not buy an image, but an experience in which they take part. My works are often transmitted in the form of a protocol. I accompany the first realizations because it remains the most efficient form of transmission. There are parts that are more or less easy to redo. For example, the Pluie d’air noir piece that is currently at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris[1] is fairly complex… You have to blow into a small pipette where you have put a small amount of hot glue, producing a bubble that falls with its weight and solidifies as it falls, suspended at the end of the material that connects it to the instrument that collected it. This is one of the most complicated pieces; most are less technical than that one.

Can this stage of transmission slow down your experiments?

No, especially because I’m not very skilled myself. I don’t have any know-how; I do very simple things. Also because I hate using heavy tools that make noise. That’s why there are usually no tools, just manipulations or gestures that do not belong to sculpture but to gardening, cooking and everyday life: cutting, folding, mixing, cooking, coating, tearing etc. These are all gestures we are used to doing.

I remember an exhibition in 1997 (Gothique at the Château de Val-Freneuse) which we prepared together, you accelerated the growth of mold for the opening. So you’re playing with one of the drivers of your practice: space-time.

Yes, rooms with peeling walls (Murs de pellicule), for example. Visually it is a bit of an acceleration of time because I use a material like agar-agar that will crack in a day, whereas resistant paints take fifty years when left outside to collect moisture.

Do you want to represent this notion of time?

From the start, when I tried to make things with my hands, because of my lack of skill but also because I’m attracted to fragility. Even back at school (at Villa Arson), I made pieces that would not last very long, sometimes not even long enough to show them to the teachers! Or things would just blow up just as I was talking about them! In fact, what interested me was the lifespan of things, and so I became against objects manufactured to resist the passage of time.

So time plays a role in the direction you take with regard to the object?

At the beginning of my pieces, it was the material that constituted them and generated their life span. Today’s consumer goods are perverse because they are made of materials that stand the test of time just to give us the illusion of being durable, but mostly they are designed not to last. The materials of a mobile phone are made to last more than four thousand years, but the phone itself will only work for two or three years. From the outset, I took an interest in time by setting up both physical and temporal frameworks within which my work can unfold.

Yet often it overflows, like the foam in Jordi Colomer’s film The American Soup (2013). The foam quietly invades the entire kitchen while everyone is talking next door. So there is the story of frames and, at the same time, of events that put them to the test.

Indeed, for the trip to Nantes (Sortie de fontaine), two years ago, I had worked with a team of technicians on the fountain in the royal square so that it seemed out of control: the jets spat, shot out of the pools, the pools overflowed and flooded the square. And again, during my exhibition Le multivers at the Lodge in Brussels last year, I designed a “Salle des débordements” in which I gathered all the pieces that were overflowing, as well as all the bins that were overflowing. I designed a foam piece: La fontaine de 18 h, consisting in putting a bottle of beer in the freezer for two hours so that once out, it foams and overflows for twenty minutes. And I had placed this piece in front of another made of a saucepan filled with snails on a carpet (sans titre). Since the smell of alcohol attracts snails because they eat decomposing matter, once the pan was opened, they overflowed to go to the beer, leaving traces on the carpet. These are controlled overflows, representing the overflow because I am not really overwhelmed.

Isn’t this interplay between the representation of overflow and overflow itself also a way to experiment in a more critical or political space?

I myself have been overwhelmed by exhibitions. For example, I remember an overflow in 1997: fruit flies had invaded the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, which was not planned. Since there were other works in the museum, a guard took the initiative to swat them. We are constantly making things that are beyond our control; this is the sad history of our civilization. The danger is to imagine controlling them. If you put yourself in the position of the master, you have to expect to be overwhelmed at some point – this is also true politically. On the other hand, if you view the thing in front of you as something you have to make do with, then you can enter into other types of exchanges and experiences. It seems to me that this is also what generates the appeal of the “artist’s life”; it’s not about being an engineer and mastering everything.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

Circling back to experimentation, although education is cheaper in France, many art school students today take out loans to pay for their studies. Not to mention the USA where art school costs 15,000 euros a year. With 60,000 euros in debt, there is no room for the unknown. You are immediately thrown into project culture of quantifying everything until there is no room left for anything that does not come directly from you. So you impose your will from beginning to end. When I left school in the early 1990s, even though I have been exhibiting at the gallery Art : Concept since 1991, I was able to show my work and make it in places that were not directly related to sales. Today, if you are a young artist and you make work only for fairs and galleries, it puts a lot of strict limitations on you. Of course there will always be many excellent things in these settings, but the setting itself limits, standardizes and “shapes” art. Too many artists produce work for art fairs, which is not a space for experimentation. Experimentation still exists today, but not in the dominant venues of contemporary art. Instead it has moved to the margins and unofficial venues. It occupies other lands, sometimes far from the capitals, in collectives that pursue life experiences that are far-removed from the art market…

Exhibition view : Michel Blazy, We were the robots, Moody Center for Contemporary Arts, Houston, TX, 2019.

Photo : Nash Baker

Courtesy of the artist & Art: Concept

Exhibition view: Cachou hibiscus, 2012-2017 VC

Cachou Lajaunie box, hibiscus, soil, water, variable dimensions

Photo: Claire Dorn

Courtesy of the artist & Art: Concept, Paris

Exhibition view: Téléphone (2015)

Phone, plants, soil, water, variable dimensions

Photo: Claire Dorn

Courtesy of the artist & Art: Concept

Exhibition view: Pull Over Time (2015), detail

clothes, sneakers, sound and image equipment, plants, water, variable dimensions

Photo: Blaise Adilon / Biennale de Lyon

Courtesy of the artist & Art: Concept

Exhibition view: Le Mur de Pellicules et Fontaine de mousse, 2012, variable dimensions

Exhibition view : Plus de croissance, un capitalisme idéal, Ferme du Buisson, Noisiel, 2012

Photo : Aurélien Mole

Courtesy of the artist & Art: Concept

Exhibition view: Sculpture: Bar à oranges, 2012, detail

mix media, variable dimensions

Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Courtesy of the artist & Art: Concept

Exhibition view: Mille feuilles, (1993-1994)

Pink toilet paper, variable dimensions

Exhibition view: A pied d’oeuvre(s), Monnaie de Paris, (2017)

Photos : Martin Argyroglo

Courtesy of the artist & Art: Concept

Exhibition view: Le lâcher d’escargots (2009)

snails, brown carpet, variable dimensions

Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Courtesy of the artist & Art: Concept

Pluie d’air noir (1996)

***

Interview by Lise Guéhenneux