Paul Smith - Wool suit, silk shirt

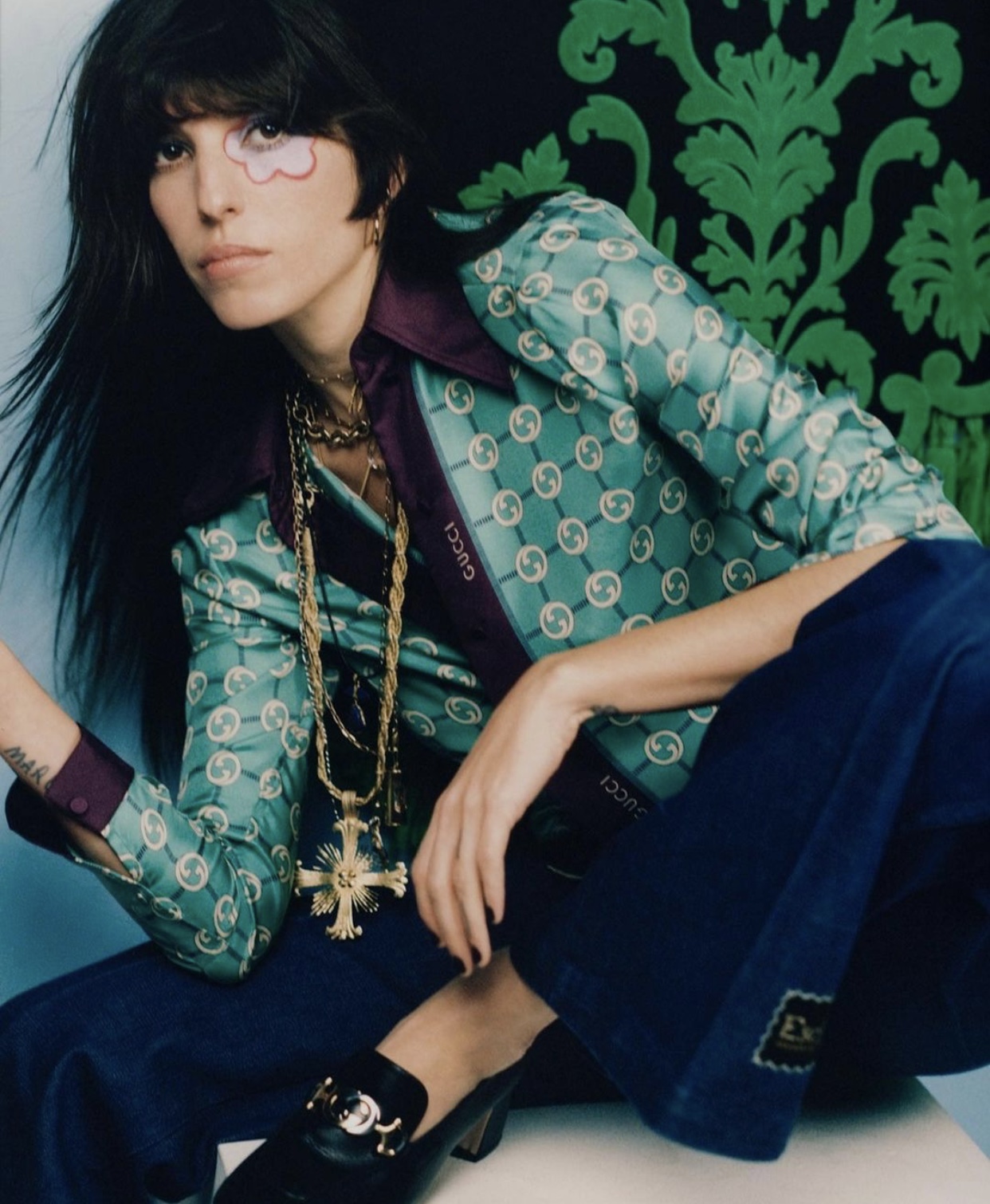

A MEETING WITH HELENA HAUFF

By Alice Butterlin

Dark, ragged, grimy and brutal, the gnarly tracks of German techno producer Helena Hauff have kept the planet’s dance floors pumping for over six years, from tiny underground clubs like Golden Pudel in Hamburg to the world’s biggest music festivals. Known for her sets mixed exclusively with her impressive vinyl collection, Helena Hauff cuts an exceptional figure at a time when USB drives stuffed with MP3s have widely replaced turntables and wax. But when she’s behind the decks, it’s sure to be an unforgettable night with her discerning selection of bangers ranging from acid house to industrial techno and EBM. And when she steps into the producer role, she loves nothing more than to flow with her analog instruments in jam sessions that lead to cold, pulsating albums perfect for on and off the dance floor. We sat down with her during her recent trip to Paris for the Peacock Society festival, where she played b2b with DJ Stingray, the Detroit producer connected with the legendary duo Drexciya.

This issue is devoted to dreams. How much does your subconscious guide you when you make music?

I’m a very rational and logical person. I’m not interested in the supernatural, superstitions or horoscopes. I’m more down to earth than spiritual. I used to be deep into physics, and even studied it for a while. If you can’t explain something rationally, I don’t want to know about it. But for some strange reason, music is the only activity where I just let myself go. I stop thinking and I trust my instinct. Making music is very physical for me; I’m always standing on my feet in front of equipment. I’m not sitting behind a computer moving a mouse. I don’t plan much; I just let things happen. Most of the tracks I’ve released were recorded in a single live take. It captures the moment and the way I’m feeling. I try out different things and if it seems good, I’ll leave it. It’s funny because I’m not at all like that in my ordinary life. (laughs) Anyone who knows me personally probably knows that I make music in a totally different way. I’m more attentive to my feelings when I’m making sounds. That’s probably why I like doing it so much.

I read that the human brain only uses five percent of its total capacity. So when you are working with your equipment, it’s almost like you are pushing the machine’s “brain” beyond what it’s programmed to do.

I always thought it would be amazing to be able to make music just with your thoughts. Sometimes your equipment or computer can get in the way of what you really want to say. Sometimes I have a song in mind that seems like the best track in the world, but I can’t really recreate it. I can’t even really think about it because it doesn’t exist. I would love to have a machine that can read my mind. Well, actually no, that would be a little extreme. But it would be great to plug something into my brain that would make music appear. Although I wouldn’t want just anyone to have access to my thoughts. Maybe we shouldn’t push technology too far. (laughs) Anyway, I think we have more music in us than we know. Looking back at the history of music, it was always a new technology that created a new sound. There was the acoustic guitar and then the electric guitar brought along a new sound. Computers are the latest technology to have a major influence on music, and we haven’t really seen anything new since then. Things may sound different than ten or twenty years ago, but we haven’t really seen any new musical genres.

If we actually started extracting music from our brains, it would probably be wholly unlike any music we know today. Like a sort of extraterrestrial music. But it’s interesting that dreams are the only gateway to the other 95% of our brains.

Dreams are strange things, especially when they tell realistic stories. How is it possible that we live something several times over in our dreams, but then we can never remember the end of the story? I had a recurring dream when I was a kid: I was in a labyrinth and at the end there was a little wooden figurine that I thought was really scary. I dreamed about it so many times, but every time I found myself in the labyrinth, I never remembered that the figurine was going to come back. How can our brains trick us like that? Clearly my brain knew the end of the story, but it never told me. (laughs) We can’t trust our own minds.

How did you start mixing?

I actually started producing music in 2008. I was at art school at the time and there was a recording studio, but it only had a MIDI keyboard and computer. There weren’t any real instruments. Eventually I got bored with producing, so I quit. Then I started collecting vinyl and got interested in DJing. A few years later, a friend of mine invited me to try out all the equipment in their studio. I fell in love! So then I started buying synths and getting back into music. That’s how it all started.

Do you remember the moment when you discovered DJing?

That’s a tough one to answer because when I was a teen, I spent my time recording music on cassettes. I was absolutely obsessed. I would go to the library to borrow tons of CDs and then copy them onto my cassettes. But I didn’t really know what it meant to be a DJ. (laughs) I also remember sitting in front of the TV in the 90s watching the Love Parade. I thought DJs were the coolest people in the world. When I recorded my cassettes, I didn’t think of it as mixing, even though in theory that’s kind of what I was doing. Then when I was eighteen I started going out to clubs. I got to see actual DJs at work and I thought it was fascinating. It only took one year of going to clubs before I wanted to do it, too. I started meeting people who had turntables at home and I would beg them to let me try it out. Someone let me once, but that was the only time. (laughs)

Did you scratch?

(laughs) No, I don’t know how to scratch at all. I would love to be one of those DJs who does scratch battles. It’s impressive. It takes a lot of training. Anyway, I had a bizarre obsession with turntables; I always wanted to get my hands on them. I would even see these giant turntables in my dreams, where I could finally touch them. It almost became like a fetish. (laughs) So in 2009, I decided to finally take the plunge and buy two turntables. Two months later, I was playing in front of crowds and I never stopped.

Did you already have a big record collection at the time?

Not really. I only had about fifty records when I bought my turntables. Since I really wanted to be a DJ, I would go to record stores and buy out almost the entire store. I bought so many terrible albums. (laughs) When I bought my first techno album, I listened to it at 33 RPM at the store, even though it was supposed to be played at 45 RPM. I thought the sound was interesting and unique. I didn’t realize until I got home that I had listened to it at the wrong speed. It turned out I had bought a really annoying record. (laughs) But sometimes I will still play discs at the wrong speed if I think it works.

Mixing vinyl alone is a bold choice. It’s become a rare choice among DJs. Did DJs mix vinyl when you started out?

Yes. There was almost nothing but vinyl at the time. In Germany, a lot of local DJs still mix vinyl. German clubs have some really good vinyl setups. I never worried about mixing until 2013, when I started traveling. I played in London in a tiny basement club, and it was the first time I had technical problems. I didn’t even understand what was going on. (laughs) Unfortunately it happens a lot and there’s not really anything you can do about it. It doesn’t really bother me, but what’s annoying is that other DJs use digital and the audience doesn’t always notice the difference. Some people think I don’t know how to mix. They think it’s my fault if a set crashes, when it’s really just a technical problem. But I’m the only one who has that problem because I’m the only one who plays vinyl. (laughs) A guy came up to me after a set once and told me I needed to practice mixing because I wasn’t very good. I was like, “Excuse me?!” He probably wouldn’t have said anything twenty years ago, because nearly everyone was dealing with the same problems.

Do you think audiences twenty years ago understood that things could go off the rails and that sets are not always linear?

Yes, probably. Now it’s like people demand total perfection, which is boring. (laughs) I think it’s great when you hear a DJ working hard. Of course, it’s not so great to hear a DJ mess up, but I like sets that have texture, not just the same sound from start to finish. But there are a lot of people who don’t really like that kind of thing. (laughs) Especially at big festivals where people expect things to sound the exact same and are shocked when that’s not the case.

Speaking of crowds, I imagine you started out playing smaller venues. How did you adapt to the massive festival crowds? Is it another process?

It’s different, but I didn’t get famous overnight. I wasn’t thrust onto the biggest stage in the world just like that. I played in small clubs that gradually got larger, and then at festivals, but first on small stages before moving to the main stage. So you get used to it along the way. I like both because there is a different energy. I like playing for thousands of people and seeing them shout and throw their hands in the air. It’s a great ego boost – as long as it goes well… (laughs)

Are you fully present during your sets, or do you let the music take over like an out of body experience?

That’s an interesting question. It depends on how much alcohol I’m drinking. (laughs) I’m usually pretty focused and present, but the magic moment is when everything becomes one: the crowd, the music, you and your turntables… You don’t even have to think about what you’re doing anymore. You stop asking yourself what your next track will be, what the atmosphere is like, what the crowd wants. When you are one with your instrument, it’s like butter spread over hot toast. I like when things happen naturally and effortlessly, it’s nice. But it doesn’t happen very often. Even if it’s not perfect, it’s still a lot of fun.

I imagine that your mindset changes depending on whether or not you are recording your set, like for the Boiler Room videos.

I don’t really like recording my sets for several reasons. First, I never know what the setup will be like or if I’ll run into technical problems. When it’s just you and the audience, it’s not really a big deal if it’s not perfect. Everyone can feel the energy. People are much more critical online. “She can do better.” “The flow isn’t that great.” The camera can also mess with you and cause you to lose your composure. You want to play a perfect set because it will be recorded for all eternity, so you end up not taking many risks. Since I only play vinyl, if I just have one bag for the weekend, all my sets will be pretty similar. Especially if I’m mixing for three hours every night, I’m going to use everything in my bag. I want to surprise people by playing something new. If everything is filmed or recorded, I’ll run out of discs that people haven’t heard. Sometimes I agree to be recorded, but not very often. For the audience, it’s an experience that is lived in the moment, something we share between us. It’s nice to have a moment that exists on its own, no need to immortalize it.

Nowadays, people feel the need to capture every instant of their day or night so they can let the whole world know what they are up to. It’s to the point that if there are no photos, it didn’t really happen.

Yes, that’s something I think about a lot. I’m not on social media, but I think experiences should be good enough to exist on their own. I don’t want to devalue them by making them permanent. I want them to be meaningful even when they are over. Oddly enough, I feel like if there are no photos, then it was good enough to just be in the moment and nothing but the moment. But it’s also true that when you can share it with someone else, it’s different than experiencing it on your own. When you’re alone, you have more of a reflex to take a photo because there’s no one else there to see it with you.

It’s also a way to shape your identity, through photos of things you’ve seen, what you ate or what you danced to… If you don’t post photos online, you lose your passport in a way.

I can understand that. Sometimes I think: “Oh, this would be perfect for Instagram”, you know. Like when you see something cool, or you have a killer outfit or do something funny. But ultimately, it’s a luxury to keep these moments in your own memory. Like when you’re young and you get dressed up at home and dance all alone in front of the mirror. It seemed like enough back then; I never felt the need to show anyone what I was doing. Maybe we want to exhibit ourselves so much today simply because we have the means to do so now. Back when it wasn’t so easy, it didn’t even cross our minds. Social media can totally transform our activities. You start out doing things you actually like doing and then you get likes and compliments, so automatically you convince yourself that you should keep doing more of the same. Eventually you get to a point where you start doing things you don’t even like just to get a certain reaction. Your virtual image dictates what you do with your life rather than simply documenting it.

Do you find it strange to be photographed and filmed so much?

I don’t really care. I’m not totally against it. I’m not a cynical person. I don’t hate people who record me; I can’t complain. (laughs) I don’t always understand what’s going on – or how people behave. But I’m sure I would like it if I got on social media. I understand why people think it’s fun. But for now, I’m glad that I don’t really have to think about it. I don’t have to please anyone.

The notion of “safe spaces” in clubs has become an important topic in recent years. It’s the idea that clubs can promote social and political ideas and offer an inclusive space for everyone, regardless of their background or sexual orientation. What do you think about it?

It’s a good thing. When you think back to the origins of electronic club culture, with Chicago house and all that, it came out of the gay scene and everyone who felt marginalized. They would get together in places where they felt safe and where no one would stare at them. So safe spaces have always been a big part of club culture. It’s good to keep that in mind and try to create spaces that respect these principles. One of the reasons that smaller clubs are more enjoyable is that the bigger the crowd, the harder it is to know what’s going on. I love playing big clubs, but I can’t always make sure that women are safe, for example. I can’t see anything! In smaller clubs, there is a stronger connection to the audience, but that doesn’t always mean that it’s safer. But it’s a little more intimate and everyone takes care of each other.

Several club nights in Paris have promoted the idea of “safe spaces”, but ultimately failed to put it into practice. The organizers realized that it’s harder to achieve than they thought. Do you think creating a 100% “safe space” is utopian?

Yes, I don’t think it’s possible. Because there will always be people who get out of hand, especially with drugs. The nicest person in the world can suddenly turn into a monster by taking the wrong pill or having one too many drinks. And anyway, not everyone is a nice person to begin with. As a club, even if you do your best, it doesn’t always mean you will create the perfect club night. But if you keep your eyes peeled and make sure everything is going well, that’s already a good start. But I also don’t want to see clubs full of security guards. Can you imagine if there were cameras in the bathrooms or things like that? You have to place a minimum of trust in people and hope things won’t take a bad turn. Society today is obsessed with making everything as safe as possible. Cars have to have the perfect material, an airbag and this and that… It doesn’t always make things the most fun. It’s good to take risks from time to time. Okay, we can’t really compare a car and a club. (laughs) But there are cameras everywhere today… There are so many things we’re not allowed to do; we can’t even cross the street on a red light, even if the street is totally empty. We should be able to assume that people are reasonable adults who are capable of thinking for themselves. Of course they might misbehave, but that’s the risk you have to take to have a certain amount of freedom.

Much of your work consists in finding new tracks. How do you go about it?

Mostly on the web. Online record stores like Juno. I also spend a lot of time on Discogs and at record stores. I do a little bit of everything. We have great record stores in Hamburg. What I love there is that you find things you’ve never heard before. When you’re on YouTube, you quickly fall into a loop. You start listening to a certain sound, but it never goes very far. After four clicks you stumble on a video that has over a million views. I’m always frustrated when I go on YouTube to find new stuff. One minute you’re listening to a super weird track from 1999 with just a hundred views, then three clicks later it’s…

Aphex Twin.

Yep, that’s it. And another click later you’re back to Solomun’s Boiler Room set. Obviously I don’t have anything against them. (laughs) It’s a system that works for people who don’t really know anything about a particular genre. It’s nice but it’s limited. At a record store, there is an actual person there who pre-selects things for you with all their musical knowledge. The human aspect of record stores is a beautiful thing. Someone can recommend something to you because they know you personally, as well as all your idiosyncrasies. It’s not an algorithm, so when you find something new, it’s always more interesting. Humans are great. (laughs)

Algorithms let everyone feel like they’re a digger.

Yes, I’m not sure about how algorithms work. If you pay for clicks or likes, maybe your video has a better shot at getting recommended. I’m totally lost when it comes to those things. Sometimes I’m baffled by how a totally obscure album will suddenly become super popular. It’s strange. But sometimes it just comes down to an influential person sharing or talking about an album. I remember when I mixed for Boiler Room and they asked me to show a picture disc of an electronic track put out by Solar One Music for the camera. They thought it was cool. Then a few weeks later, Nina Kraviz bought it at a record store and posted it online. It became the best selling album in their catalog. They told me that everyone was asking for it. But when the artist released their next album, no one wanted it. The first one blew up just because it was shown in an online video. It’s pretty simple in the end. (laughs)

Since you play in Berlin a lot, have you noticed any changes in the nightlife? At one time it was the place to be for techno in Europe, but what is it like now?

I think I showed up too late to notice any of that. I think things were really weird in West Berlin during the 80s, before the wall fell. Then after it came down, everything blew up with tons of illegal raves. The 90s were the Golden Age for Berlin, but I was still too young so I didn’t see any of it. The first time I played there was in 2011, so not that long ago. I haven’t noticed any major changes. I played at ://about blank in 2012 and it was cool. It’s hard to say, but I haven’t been back there in four years.

Do you have any favorite cities to play in?

There are a lot! I always love playing in England, especially London. A lot of Londoners don’t like living there, but I love it because the crowd is always wild and really loves the genre of music I play. But for the average person going to a London club, it can be tedious. First of all, it takes two hours to get there, and then you probably have to spend two hours in line before you get in. You get searched from head to toe, they scan your passport… You can’t smoke anywhere, there’s no reentry if you leave and drink prices are exorbitant. Of course, there are underground clubs, but it’s harder to go out in London than in Berlin. I also like playing in Madrid and Athens. Russia, too. They have underground parties where people go totally wild. It’s hard for them to put anything together because it’s Russia, but their club nights are definitely worth checking out. And I’ve had some amazing times in Paris, too.

Your second album Qualm came out last summer. Looking back, how do you think it was received?

I think it was received well, but it also received some mixed reviews. A lot of people didn’t really understand it or like it. It’s kind of a club album, but also not really. And it’s not really an album to listen to at home, so most people just didn’t know where to play it. I actually haven’t listened to it in a long time. Maybe I’ll listen to it in a few months to see what I think about it. I change my mind a lot. I’ll like an album I made, and then not like it anymore. It’s a maddening spiral. (laughs) There are some tracks from my past that I wish I’d never released. There are others that I’ve learned to love again. A lot of artists feel the same way. I’m very critical of my work and I often think my music isn’t good enough. But sometimes I try to take a step back and listen to my tracks as if someone else had made them. I like thinking, “Oh, I made this?” One time a DJ told me about a time he was at a club, and another DJ played a song he liked. He asked him what it was and the DJ told him that it was his song! I don’t know how drunk he was. (laughs) I couldn’t stop laughing when I heard that story.

On Qualm, from the very first track, we hear all these very raw and rough machine sounds. Does it seem like taking a punk approach today means recording as close to live as possible? That’s what throws people off the most.

I think the people who liked that album liked it for all the same reasons as you. The fact that it just is. It’s not overproduced and definitely not perfect. If I had a manager, they definitely would not have wanted me to release it. It’s not pop at all; there are no real melodies. It’s not made to sell and it won’t make me a high-profile artist. But it’s also what people like about it. I got several amazing reviews from journalists. Some people said it sounded lazy. But to be fair, I am lazy! (laughs)

Technical skill doesn’t always translate to good music. A super technical guitar solo that goes on for five minutes does not necessarily make a good song.

Yes, that’s true. I’ve always liked simple things. Especially when it comes to techno, I’ve always loved raw and understated sounds. It has to be interesting, but I like simplicity in musical structure. I’ve always found it harder to make basic, stripped down, almost minimalist stuff. It’s easy to layer up plenty of different things, a melody, a break, then another melody and voice. Creating something from a minimalist approach is not as easy.

Interview: Alice Butterlin

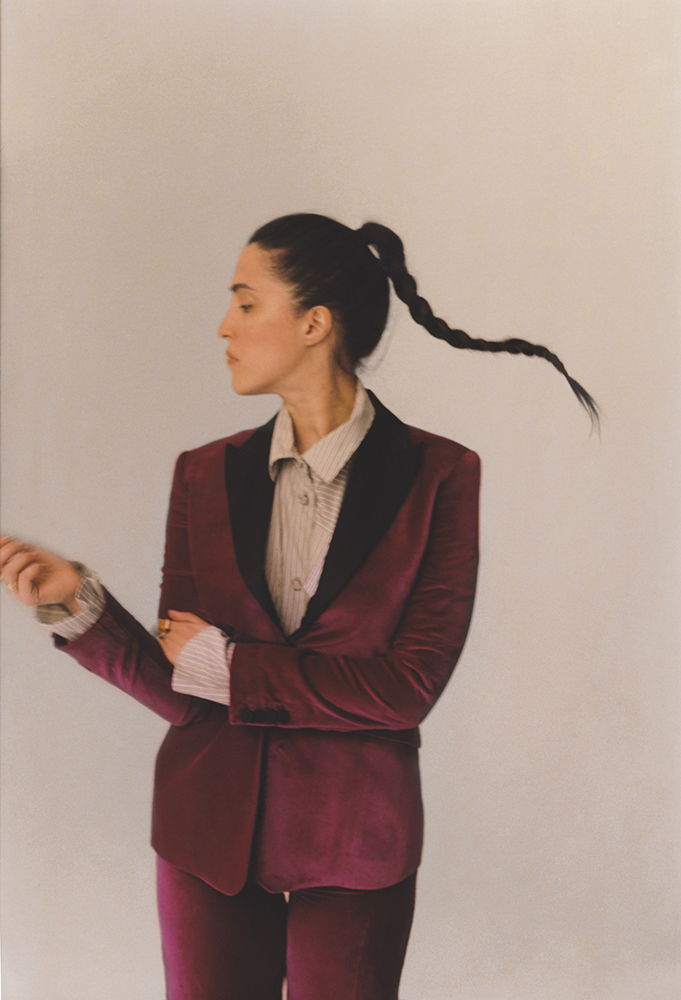

Paul Smith – Wool suit, Camper – Leather pix boots

Paul Smith – Wool suit

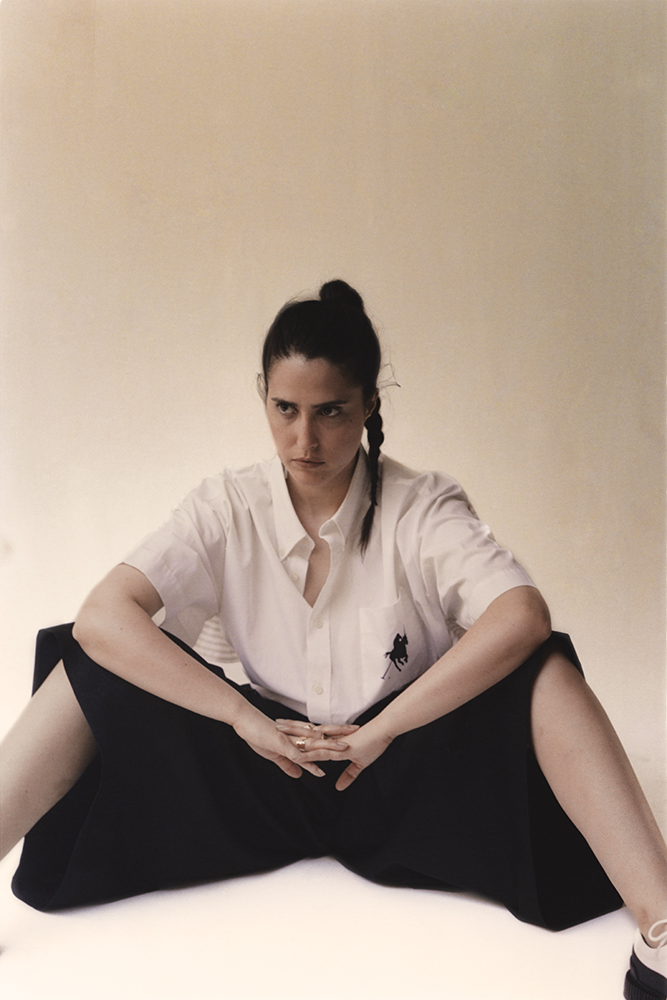

Kimhekim – Cotton cameron shirt

Y-3 – Sneakers Kyoi trail

Paul Smith – Silk dress, leather loafers

Wendy Jim – Cotton shirt

Paul Smith – Wool pants

Camper – Leather pix boots

Paul Smith – Wool suit

DDP & Neith Nyer – Cotton shirt

***

Photographer : Bertrand Jeannot

Stylist : Armelle Leturcq

Hair : Natsumi Ebiko

Make up : Aya Murai using Nars Cosmetics

Stylist assistant : Pauline Grosjean