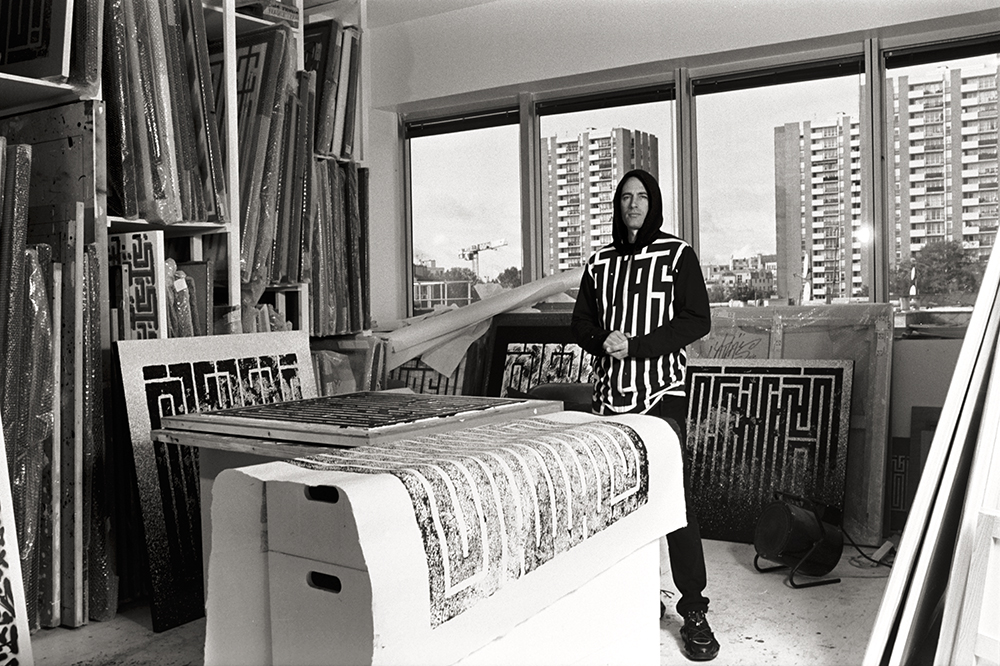

Dior - cotton shirt, D-connect neoprene sneakers / The dancer III & IV (2019), polystyrene, polyurethane resin, fiberglass, steel skeleton, pollutions particles, Courtesy the artist, CLEARING New York / Bruxelles

A MEETING BETWEEN MARGUERITE HUMEAU & ARMELLE LETURCQ

By Armelle Leturcq

A finalist for the Marcel Duchamp Prize, Marguerite Humeau will exhibit in this context at the Centre Pompidou through January 6 and as part of the exhibition You at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris through February 16. She is also taking part in the Dior Lady Art project, which selects a handful of artists every year to reinterpret the legendary Lady Dior bag. Having studied textiles and design, she had developed a unique offering in line with her practice, which stretches far beyond the usual artistic categories. In her work, Humeau experiments through an intensive research process that places her works within their own mythology. Her first project, based on an imaginary recreation of the sounds of prehistoric creatures, earned her the interest of several art galleries and announced the obsession that would stick with her work through the present: to make the past more material in order to better understand our present and recontextualize our very existence…

I’d like to look back on your journey. How did you get into art? What did you study?

I first studied textiles at the Olivier de Serre school in Paris and then I went to Eindhoven to do industrial design at the Design Academy. Then I moved to London to study at the Royal College of Art, in a department called “Design Interactions”. It was created by a group of product designers who wanted to push design beyond purely functional uses to question the impact of new technologies on everyday life. The department was created by Dunne & Raby, the most important designers of a movement called critical design and then speculative design. I mention so many details because I think the methods we developed during those two years at Royal College are still quite present in my practice: speculation, research, bringing together broad teams of researchers from extremely diverse fields and asking them to formulate hypotheses on certain subjects with me. Then we bring these hypotheses to life in the form of installations. That method comes directly from my two years at Royal College. I was still in design at the time, but my diploma project was the work that is currently on display at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris: the Opera of Prehistoric Creatures. For that project I came up with the idea of resurrecting the sounds of prehistoric creatures by reproducing their vocal organs. I thought I was going to find data fairly quickly, but I realized that there really wasn’t much data available. So I did my best to recreate them on my own. I worked with researchers, zoologists and paleontologists from all over the world who are specialists in vocal organs and mammals, etc. Then I filled in the gaps for all the missing data.

Was it a sound-only project?

They are sculptures: scale reconstructions of the sound production organs of an imperial mammoth, a prehistoric whale that lived both underwater and on land, and a prehistoric boar that scientists call the “pig terminator”. They were all carved from computer-generated models. I also worked with engineers and a surgeon specialized in laryngeal prostheses to create the vocal cords. There is a whole latex system that vibrates and produces sound when compressed air is injected into the sculpture. They are a bit like musical instruments, and all the sound is analog. I also worked with a voice synthesis researcher who created a program that allows each creature to sing or speak. They all listen to each other and as they go along, try to imitate each other and their language becomes more and more evolved. It’s as if we cloned the creatures, allowed them to be reborn today and triggered a completely artificial form of evolution all from scratch, by imitating the patterns of language evolution in animals and also in humans. Then I did several group exhibitions with a lot of help from Mark Leckey, an English artist who won the Turner Prize. He saw my diploma project almost by chance when he was organizing an exhibition that traveled to several galleries in England, notably focusing on the subject of technological animism. He included some of my creatures in his exhibition. It was a sort of steppingstone for me. Then I met Hans Ulrich Obrist who invited me to take part in the marathon he organizes every year at Frieze on the topic of extinction. I was working on Cleopatra’s voice for that event. That’s how it all came together. It was actually fairly late in my career when I had my first solo exhibition at an art venue. That was in 2014 and that’s when it all really started. After that, things moved pretty quickly. Six months later, I had my second solo exhibition at a project space in Berlin. Then my third was at the Palais de Tokyo. One exhibition kind of led to another since then.

You didn’t originally set out to be an artist?

I didn’t necessarily plan it, but I always wanted to be an artist. It seems like a cliché, but I carried that dream inside me. It was also on the advice of my family that I started in design. I don’t come from an artistic family, so it was somewhat scary. I didn’t necessarily have a clear idea of what I wanted to do. I started to get a very clear idea when I was in Eindhoven, but I was never accepted into an art school! I tried a few Master’s programs as different schools, but it never worked out. (laughs) It makes me laugh today because the same schools are now inviting me to teach and give talks. (laughs)

There is also a prejudice in contemporary art. People who come from design are not considered artists.

Yes, but especially in France, because in England there are no such divisions. It was really liberating to go to London because there is no hierarchy between different art fields. Many people in my department started out as artists, and then they went into design, and finally came back to art. There is no real border. That’s why I stayed there. I have the impression that things are quite free. I travel a lot for my exhibitions, but I am based in London. I have my studio there. My manufacturing workshops are also in London.

You’re not planning to move back to France?

I don’t know yet. I don’t really have a clear idea of what the future holds for me. With Brexit, it doesn’t really give the image of a country as inclusive as it has been for us foreigners until now. But we’ll see how it goes. It’s still a mystery. But I’ve lived in London for ten years. It’s my city, my home. In England I found an extremely favorable environment for emerging artists, with enough support so that they can have exhibitions all over the world.

Is it important in your approach to experiment and try new things?

It’s the core of my practice. The day I stop wanting to experiment is the day I die on the inside. (laughs) Experimenting already starts with thinking. All my works are preceded by long periods of research that are both very closed and very open, meaning that there is a very specific question that then opens up different possibilities. A large part of my work is not really visible: the design of “prototype worlds”. My studio is brimming with all sorts of maps that form a mental geography of all these different worlds. For example, for the exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo, I really thought about the whole world of elephants, how they might evolve in reality and how that civilization might actually work. That includes how they would communicate and how they would feel emotions. It’s the same process as a director planning out a whole world for a film. Experimentation is already happening at that point. Then, more practically, I am always looking for ultra-artificial and very ambiguous materials, which are both extremely vibrant and very spectral. My goal is for viewers to wonder how my sculptures can be real when they look at them. The second layer of experimentation involves systems. There aren’t many systems in this specific exhibition, even though some sound does travel through the walls. In other projects, I develop fluid systems that circulate around the space, or through the sounds that come from the sculptures themselves. For example, my last exhibition in Brussels featured a funeral rite of fish trying to revive one of their own by blowing air into their body. It’s like a ballet of lungs swelling and deflating, a company of fish that seem to dance as they try to resurrect a being that has just lost its life. It requires a lot of testing and experimentation.

It’s interesting to hear about the process of reflection and production… When you were talking about maps, what form does that take?

They are drawings. I draw a lot on massive sheets of paper. It all starts with drawing. I wanted to convey these worlds of the past and future with lines traced between the heavens, the kingdom of ghosts, immaterial beings, paradise, or perhaps the cloud today; and then below, within the Earth’s crust, there may be the underworld or underwater volcanoes. There is a relationship between different spaces and different time scales: the distant past, the distant future, the present and what happens between these time scales. Then there are the other parallel timelines. In all these parallel worlds, what happens if we pirate what really happened and deny the reality of certain facts? For the FOXP2 exhibition: what would happen if this specific gene did not mutate in humans, but in elephants? All of a sudden, it shifts our perspective and we find ourselves on another timeline where elephants evolved and not humans. I made all these maps with all these different lines. I just spend months having fun doing it. It’s like redrawing the history of humanity, from our origins to our end. The feeling I carry in me and that I try to recreate in all my exhibitions is that, ultimately, we may be no more than a blip on the radar of History, a tiny footnote. I’m interested in how we relate to these worlds that existed before and after us, and where that leaves us as humans.

So you get to you studio in the morning and start asking yourself all these questions?

Not just in my studio, but all the time. I have all these maps in my head. When I say maps with axes, it’s something very concrete. They are tools for formulating these speculations. It’s like world engineering. It starts with the maps and then I go into more detail.

Do you work on a project basis? For example, do you say to yourself: “I have an exhibition in two years, so I’m m working on this project”, or are you working on something bigger and more expansive?

That has changed. I started out working on a per-project basis, but now I’m realizing that all my projects are connected. I just came to that realization this year and it was a very nice feeling. I feel like I have defined my territory and now all I have to do is explore. Now I conceive my works as if there was a huge map of all these worlds that I explore one by one. I realized that I’m always coming back to the same questions. I talk about ancient Egypt with Cleopatra, humanity’s origins with the Venus project, a not-so-distant future with the project at the Centre Pompidou for the Marcel Duchamp Prize. I always come back the same questions: “Where do we come from? Where are we going?” And above all, the question of how new technologies are redefining life and death, such as regenerative medicine and the rise of artificial intelligence. I’m interested in how all these technologies are expanding the spectrum of possibility in terms of the meaning of life and death today. There are many other artists who are interested in these topics, too. It’s also about how we include these different forms of life in our ecosystem. And more generally, there are many movements at the moment – especially #metoo – that show that we are including more and more beings within our dominant ecosystem. Hierarchies are changing. Again, this is not specific to my work.

It’s also another way of seeing the animal world. Until now, animals have been seen only as beings to be exploited, but that is changing. There is a groundswell on the rise.

Yes, this is only the beginning. Talking with many researchers, it is clear that we are realizing that supposed human traits are not at all human-specific. It’s crazy to think that for so many years we thought that language, religion, knowledge of death and rituals were specific to humans. In many anthropology books, these are the things that define us, when in reality they are found in many other species, so that puts us back into the natural world.

Some are even starting to perceive trees as thinking beings…

Oh yeah, that’s absolutely wild. There is the example of a huge forest where on one side the trees began to get sick, and then the trees on the other side developed an antibody for the disease before they had even contracted it. That implies that they communicate in a certain way, through their roots. Clearly, we still have a lot to discover.

Some say that only ten percent of the living species on Earth are known. We don’t actually know much about our world. (laughs)

Yes, that is so clear.

What is your relationship with nature and animals? Do you have a strong personal connection to them, even though you live in the middle of London, completely disconnected from nature?

Yes. (laughs) I don’t necessarily have a strong personal relationship with nature on a daily basis, but I grew up in the countryside, so we lived in harmony with nature. It seems so cliché to say that! We were also very close to the sea. I have a very strong relationship with the sea. I’ve done a lot of sailing. But it is more so the relationship to the sublime that interests me in nature. It’s an extreme fascination and also kind of frightening. That’s the feeling I try to recreate in my exhibitions, whether physical with my sculptures or through the voices I create. For example, Cleopatra’s voice is extremely seductive and sings a love poem of her time in extinct languages. There is something exciting and seductive and at the same time frightening about it, since we realize that this voice has no soul and no body. It is a completely artificial and empty voice. I wanted my sculptures at the Centre Pompidou to be spectral, as if they came from another time and perhaps would disappear. At the same time, they are very present and concrete. They are animals that seem polluted and imbibed with a kind of grey matter that pulls them deep into the ground – in my imagination it’s the water surface. At the same time, they seem to want to rise up through a desire for transcendence. They are both extremely airy and dynamic and extremely heavy. They are ultra-seductive and at the same time, when you get close to them, there is something visceral. You have the impression of seeing their skin and the inside of their entrails. So the question of the sublime is very present in my work.

Are you afraid of beauty? Beauty is often avoided in contemporary art…

Yes, I find it interesting to create an ultra-seductive and beautiful experience that is at the same time frightening, either because of the topic or because of the feeling you have when you get close to it. Ultra-artificiality and what people can call “beauty” is always linked to a certain form of horror. It’s related to the artificiality of these bodies and their emptiness. Seduction is a tool that I play with. It is never just what it is; it’s a tool to for generating confusion and provoking a much more ambiguous feeling.

Are your works complicated to produce?

Yes, they are big productions. At first, I financed them on my own by taking out bank loans and working. Then the Clearing gallery came along and changed things for me. My goal was to be able to live off my work and then reinvest in production. But it’s clear that my practice is ambitious in terms of scale and resources. It’s also hyper rigorous because nothing is left to chance. It’s very deliberate. I had to work hard to find the right craftspeople. There are only a few people who truly understand what is involved in producing these works.

Do you work with a 3D printer to make prototypes?

No. I do the drawing first, then I work in collaboration with different craftsmen who translate my designs into 3D models. Then we sculpt them in foam blocks with a milling machine that goes around these blocks and cuts out the shape. Then it is sent to another craftsperson specialized in molding and resin. That’s who we develop all the materials with. He’s probably one of the most important people in my life. He has an endless knowledge of the possibilities and has a very refined taste and choices. I have total confidence in him. During very busy periods, I’m not always able to see the finished sculptures before they arrive, but they are always perfect.

Are there any artists who have influenced you?

Yes, there are plenty of them. The first is director David Cronenberg.

Especially for the movie Existenz, I imagine.

And Videodrome as well, to an extent.

We names our magazine Crash partly as an homage to his film and the original novel by J.G. Ballard.

That movie is crazy. What fascinates me about Cronenberg’s work, even more than any one of his films, is the evolution of his relationship to the body. His horror was extremely gory in the 1970s and 1980s, and it became more and more internalized until the ultra-seductive horror of Cosmopolis. When we were talking about beauty earlier, that’s exactly what it is. The Cosmopolis limousine is incredibly beautiful and ultra-artificial. Between the tension of these surfaces, we gradually see the horror of global financial systems emerging in Robert Pattinson’s speech. It depicts how horror today is no longer necessarily visual but has also become psychological. It’s good that we’re talking about it because it lines up with what I said before about beauty.

It’s true that there is a clear link with your work.

I love the director Apichatpong Weerasethakul who won the Golden Palm at Cannes in 2010 for his film Uncle Boonmee. For me, that film is also related to Cronenberg: the question of presence, of the supernatural body that exists in his cinema without any special effects. It’s about ghosts, or presences between life and death, about the undead in fact.

So you’re mostly inspired by filmmakers?

No, there are artists, too. Pierre Huyghe is inspiring for our entire generation. He is to me anyway. He still has a big influence on me.

And Matthew Barney?

Yes, Matthew Barney, especially his work Cremaster when I was a student. I also really like the work of Ed Atkins and Mark Leckey. All the artists I love work on the same topics: the presence of the living body, the dead body, and all the states in between.

What about your collaboration with Dior?

I was contacted by Dior a year ago during Art Basel Miami. They offered me a carte blanche invitation to “reinvent the Lady Dior bag”. They really gave me free reign, too, which I liked. They are very respectful of the artists’ work and their projects are very radical. They opened up a huge field of technical possibilities for me to carry out this project. My initial idea came from a conference I had seen some time ago with researcher Mark Wigley. He talked about the flints used in prehistoric times, commenting that he couldn’t understand how it was possible that so much of the flint we have found shows so few signs of damage. If what we believe is true – that they were used as knives to cut all kinds of things – then most of them should have been in much worse condition. He said that the truth may turn out to be nothing at all like we imagined.

They are works of art. (laughs)

He said: “they may be luxury accessories from prehistoric times”. It was a way to show one’s status by showing what type of stone one was able to possess, and how the skills of stonemasons made the piece as fine as possible. What if flints were the Lady Dior bag of our time? I loved that idea and wanted to pursue it in a rather literal way, by trying to create a material that would be like a fabric but would look like stone, maybe alabaster. At the same time, I went to Pompeii and the Archaeology Museum in Naples, which presents the entire collection of glass and alabaster pieces from Pompeii. I discovered an incredible funeral urn made of alabaster and rock crystal. It had twisted patterns and looked like tanned skin. The surface was so thin it was transparent. It was both ultra-organic and at the same time like stone, since at times you could see the veins of alabaster. So that was my starting point. Then Dior began to introduce me to a whole series of materials and samples and the idea developed over time. I thought maybe it was a living bag. What would happen if we took the Lady Dior bag and put it in a big wind tunnel, for example, like the ones we use in aviation testing? What would happen if the wind rushed in and it morphed into a kind of abstract creature, both a bag and something else? The bag itself looks like a still from an animation. The funny thing is that part of Dior’s manufacturing workshop works for the aeronautics industry. I decided I wanted to design it as a sculpture by using the same development process. So I designed the 3D form and sent it to the Dior workshop. But they couldn’t use it as it was, so they had to ask one of their engineers to recreate it for their software. It’s funny, it was an aeronautical engineer who recreated the 3D model. We modelled the folds to represent a skin and a drape. I also wanted to remove the charms so that everything would disappear into the drape. It’s like an inside joke for people familiar with the bag. If you look close, you can see the letters of Dior in the folds of the bag.

The good thing is that it’s lightweight. You can really use it.

Would you wear it?

Yes.

I was really fascinated by one of Dior’s machines, a 3D printer that can print in color, but not uniformly. For example, in this case, it can print marble with all its veins in the precise spot where the veins are. We started working in that direction, but I thought it was too literal. We tested the material and I thought it was really beautiful, like the pearly shells you find on the beach. At the same time, the lines reminded me of weaving or a printed fabric that becomes a sculpture.

It gives it a prototype aspect. When I first saw it, I wondered if it was a prototype.

Yes, it creates a form of ambiguity. And then for the details, it was really interesting for me to understand what makes an object portable or luxurious and what details are important. With Dior, we worked on developing the material for the handle.

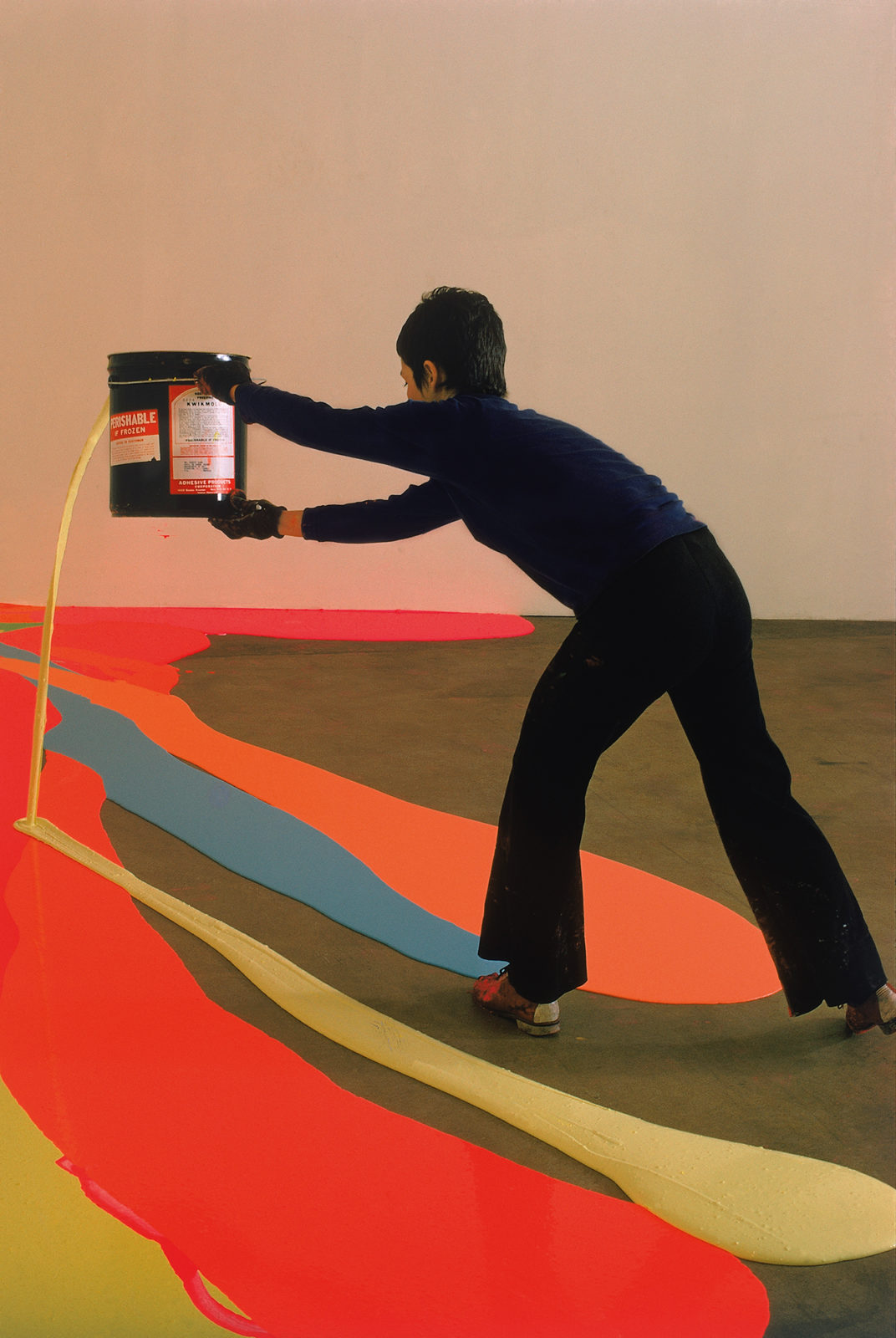

The dancer I & II (2019), polystyrene, polyurethane resin, fiberglass, steel skeleton, pollutions particles

Courtesy the artist, CLEARING New York / Bruxelles

Dior – Lady Art limited edition in collaboration with Marguerite Humeau, Lady Dior bag reinterpreted in 3D Print technique, organic compound handle, silver metal jewelry satin finish

Dior – Lady Art limited edition in collaboration with Marguerite Humeau, Lady Dior bag reinterpreted in 3D Print technique, organic compound handle, silver metal jewelry satin finish

The dancer I (2019), polystyrene, polyurethane resin, fiberglass, steel skeleton, pollutions particles

Courtesy the artist, CLEARING New York / Bruxelles

***

Interview by Armelle Leturcq.

Photos by Gabriel Fabry and Constantin Kyriakopoulos