CHRISTOPHE HONORÉ ON CINEMA

By Crash redaction

CHRISTOPHE HONORÉ INTERVIEW ON CINEMA: WE MET FOR THE RELEASE OF HIS LATEST FILM, LES BIEN-AIMES, PRESENTED AT THE CLOSE OF THIS YEAR’S CANNES FILM FESTIVAL. HE TELLS CRASH ABOUT HIS START IN CINEMA, AS WELL AS HIS FILM AND LITERARY INSPIRATIONS. THE 1960S, ROMANTIC BACK-AND-FORTH, FRANÇOISE SAGAN, AND THE CAHTERINE DENEUVE-CHIARA MASTROIANNI DUO, ALL WITH AIRS OF ALEX BEAUPAIN: A PLUNGE INTO THE WORLD OF CHRISTOPHE HONORE.

Interview by Théo-Mario Coppola

What films most inspire you as a viewer?

My cinephilia passed through a few different phases. I’m from a small village in Brittany where film was not readily available when I was in elementary and high school. The midnight movies on France 2 television helped build my filmography. I started a film club in high school, where I showed Tenue de Soirée by Bertrand Blier and Thérèse by Alain Cavalier. The club was primarily focused on French films of the time. My family was not at all passionate about film; yet I quickly became attached to the medium, and especially directing. I remember when my mother went to see Memoirs of a French Whore by Daniel Duval. I was very young. Tess was filmed not too far away in a small castle. My grandmother lived in Nantes where I spent the summer when I was about fifteen or sixteen. There was a rerun of Jacques Demy’s Lola at the Katorza. My grandmother remembered the shoot, so we started making pilgrimages to film shoot sites. That’s where I learned that films have to be put together. While I was in high school in Rennes, we had the Grand Huit (now the TNP); it was a movie theater that organized retrospectives of directors like Bergman, Truffaut, and Antonioni. This is when my cinephilia really took off. Since I felt guilty about not attending university, I could at least convince myself that I had real work to do. My cinephilia included the major French films of the era, then the French New Wave, Resnais and Varda to Jacques Demy, as well as Ophus and Bresson, who greatly influenced him. In a general way, filmmakers led me to more filmmakers. For example, Truffaut led me to Hitchcock and Renoir. I’ve always liked the idea that films carry the mark of the directors that their directors watched and appreciated.

Speaking of influence, Jacques Demy is a name that comes to mind when watching your latest film, Les Bien-Aimés, and not only because of the songs, but also the choice of colors and dyed blonde hair.

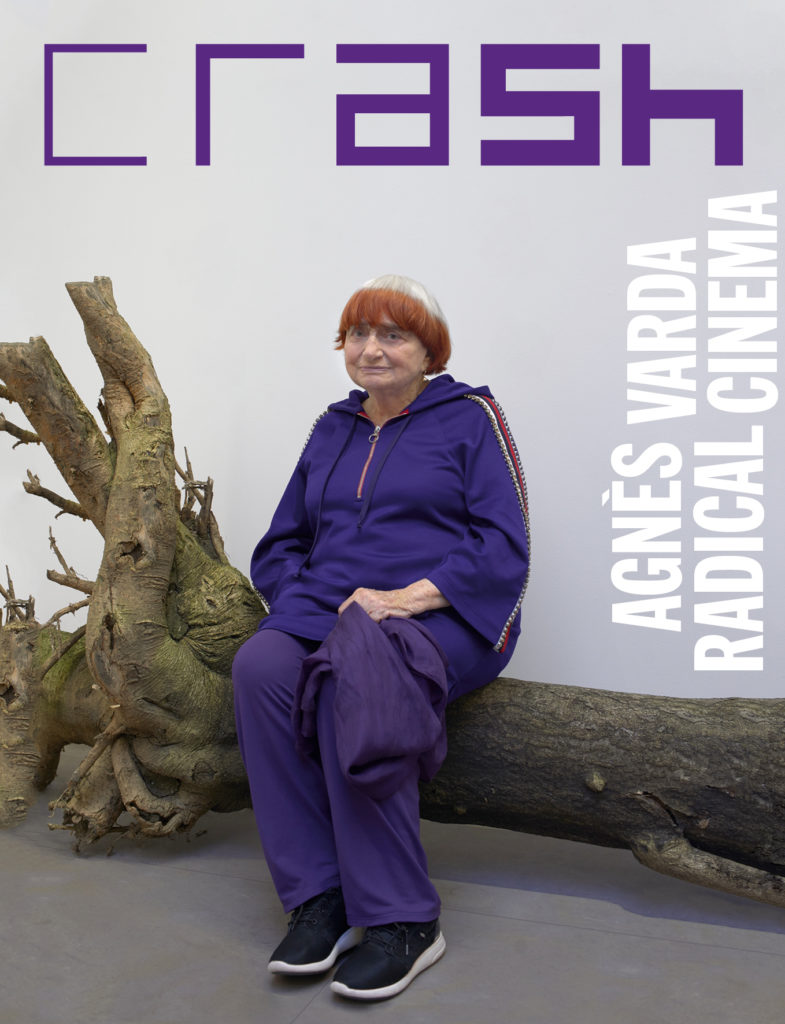

I’m aware of these influences, and I don’t think I fetishize these films. I prefer not to suppress influences, and I like when my films betray their structure. For me, this is what modernity demands. It’s interesting to leave visible traces of this mental creation process. There is no film that does not build on a previous film; there’s no “Adam and Eve” of film. For me, it’s inevitable. I know some filmmakers claim an “immaculate conception” and to have created an absolutely new form, with no references to other works. But the French cinema I like, heir to cinema of the 1960s, is the cinema of cinephiles. Agnès Varda, Claude Chabrol, and François Truffaut directed movies because they liked other directors’ movies. As for the new generation of directors I’m seeing today, they were not led to film by films, and this is entirely laudable. For me, if I had never seen films directed by others, I would never have become a director. Other peoples’ films gave me perspective. I envied them and through them I learned things about life and film.

You mentioned fetishism in connection with influences. At the beginning of Les Bien-Aimés, fetishism emerges through Madeleine’s shoe addiction – an addiction quite characteristic of the 1960s.

At the time, materialism was seen mainly as a virtue and a means for liberation. The roll of the dice that launches the story of Les Bien Aimés is indeed the theft of a pair of Roger Vivier shoes by Madeleine (Ludivine Sagnier). It’s an act of rebellion and freedom, while today, stealing a pair of Christian Louboutin shoes would imply an act of enslavement to consumer society, and not an act of rebellion. In a sense this act condemns her, because Madeleine will later be taken for a prostitute, which she isn’t. But she says to herself in her heart of hearts: “Why not? It would help me buy more shoes and take fewer risks.” So she sets foot on a new life. If a young woman stole a pair of shoes today, we would never assume she was an easy girl, as is the case with Madeleine in the 1960s. The film treats the transition from one era to the next, from one comedy of manners to another, and one vision of love to another. All this depends more on history and culture than we are generally willing to admit.

In Les Bien-Aimés, the characters and story refer directly to history: first in Prague, with the arrival of Russian soldiers in 1968, then in 2001 during the September 11th terrorist attacks.

The two lead ladies in love are very selfish. One (Madeleine) can only think of winning back her adulterous husband as Russian tanks invade Prague, while the other (Véra) is in the throes of an erotic obsession for a man she cannot have while the September 11th attacks take place. The Russian tanks end up giving Madeleine an urge for freedom; she resists and liberates herself from the bourgeois convention of marriage. On the other hand, September 11th only exacerbates Véra’s dramatic impasse and hardens her conviction of having no future. She is the archetype of the romantic heroine in love. We can thus say she dies equally of AIDS and September 11th. She’s stuck in an impasse fueled by an entire era.

How are the songs in the film structured?

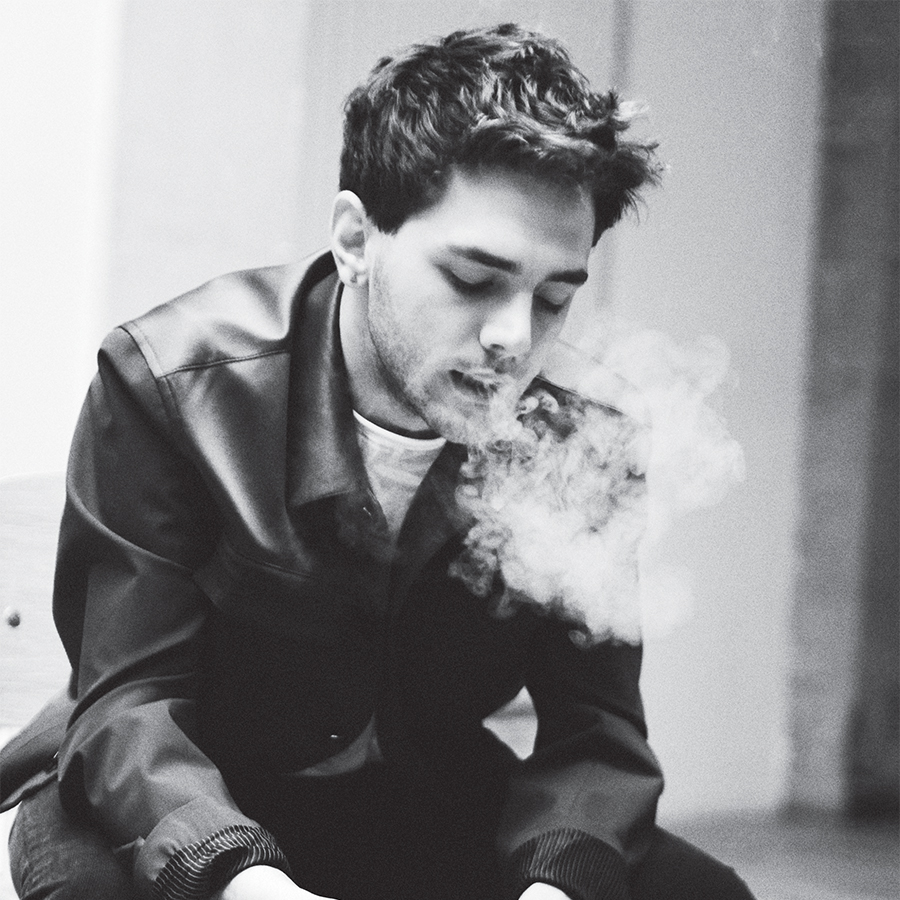

I didn’t want to lock myself into a musical, and I don’t think I made one. Les chansons d’amour (2007) was a real musical. Les Bien-Aimés is more a film set to music. Its characters are only seen in love scenes. For this reason, I thought songs would make for a rather interesting lyricism, so I asked Alex Beaupain to get involved.

Alex Beaupain is something like your Michel Legrand.

It’s true that there is a real bond between us, but it is nevertheless very different from what Jacques Demy and Michel Legrand shared. Legrand was aiming for opera and symphony, and he had the talent and ambition of a major composer. This is not Alex’s aim; he writes songs close to pop music and French standards. I explained to Alex the situation corresponding to each scene. Since I don’t write in a chronological way, I also explain the situations leading up to and following each scene, as well as a few words I’d like to hear. He then wrote the songs based on these guidelines, so they were like commissioned pieces. And Alex can tell you that I sign every e-mail with the name of a different dictator, from Bokassa and Gaddafi to Mussolini.

In one scene, Jaromil, Véra’s father, returns from Paris and goes through his daughter’s room to find Wonderful Clouds by Françoise Sagan. This reference highlights several echoes of Sagan in the film.

I thank both her and Kundera in the film’s credits. She exercised a rather strange power. She had this reputation of being a very active, superficial writer who was only interested in the bourgeois world. I reread her novels and found a much more complex, unexpected form created precisely by this discipline of levity. She invented the carefree girl in literature. Before her, literature contained characters with sex lives outside of steady relationships, but with Sagan, these adventures become romantic adventures. With this film, I wanted to work on the theme of the mixed time of love and show characters unable to forget their first loves. These characters are highly disloyal from a sexual point of view, but extremely loyal emotionally. This kind of discipline has nothing to do with morality, but is more akin to fate or destiny. Madeleine, for example, would prefer not to go back to Jaromil when he returns first in 1978, then again in 1998. She would love to sleep with him and tell herself that everything is fine, and she says it herself. When Madeleine, played by Catherine Deneuve, goes to meet her husband, after having left her lover, she confides her troubles to her daughter Véra, concluding: “Anyway, I don’t want to bother you with all that.” That kind of moment, it’s very Sagan, and this reserve in no way interferes with feeling things deeply.

Generally speaking, the characters maintain a lot of modesty amongst themselves, as in the scene between Michel Delpech and Catherine Deneuve about her character’s adventures.

This scene comes from Anna Karenina. Anna’s husband learns that his wife is adulterous, and asks her to stop talking about it and to tell no one. Thus the famous “But I’m still your wife?” reply in the novel. It’s an accorded freedom, but also an act of violence, as he places his wife in a situation of absolute guilt and accepts it. It’s a suffocating elegance.

The Catherine Deneuve-Chiara Mastroianni tandem was a great success. It’s the first time these two actresses have played the roles of mother and daughter together.

I decided to offer them the roles because I had already made several films with Chiara Mastroianni, and I knew she wouldn’t think I was taking advantage of the situation. I knew she was rather anxious to play a mother-daughter relationship. I make them sing “like mother, like daughter”, without trying to make them sing any other way. And there’s a real continuity between Catherine and Chiara. I see traces of Catherine in Chiara’s expressions and her way of acting. They envision their acting work very differently, and sometimes I felt Catherine turning a tender eye to Chiara, even though Catherine wouldn’t put it that way. As viewers, we feel Madeleine looking at Véra in a way that goes beyond a mere relationship between characters. In one sense, we’re right to ask, as the daughter of Catherine Deneuve and Marcello Mastroianni, how could she not feel like an imposter in front of the camera? But she has succeeded in prudently detaching herself from this question with choices that few actresses have. She can act on a variety of levels: both comic and tragic. Chiara is a truly great actress.

Ludivine Sagnier shows another aspect of this ability to alternate between the comic and tragic.

Ludivine indeed has this chameleon ability. It’s a gift that’s rare among our American actresses! She can play radically different characters, even characters that look very different. We even have trouble recognizing her at first, since she can fit into a wide variety of atmospheres. She’s a very joyful actress on set, always in good spirits yet also very focused. Sharing the role of Mathilde with Catherine Deneuve was disconcerting, and watching the film again with more distance, I often find that Ludivine resembles Catherine. The passage from one to the other occurs seamlessly, and we find the youth of the character and not Catherine Deneuve.

The films that inspire you also call to mind Paris. What does the French capital evoke for you?

As a child, I never went to Paris. I came for the first time at twenty-five. The city’s attractive power lies in a constant ability to marvel. I’m a lot less excited by foreign cities like Berlin or London. I spend an afternoon wandering through Paris and I have twenty ideas for a book or screenplay. I truly love this city and I feel good shooting here. I live on the line between the 10th and 11th arrondissements, a neighborhood where unexpected encounters abound. For example, I like the ability to shoot in the La Chapelle neighborhood and plunge actors as famous as Catherine Deneuve into Place Clichy, without having to block streets. For me, Paris is always eminently novelistic.