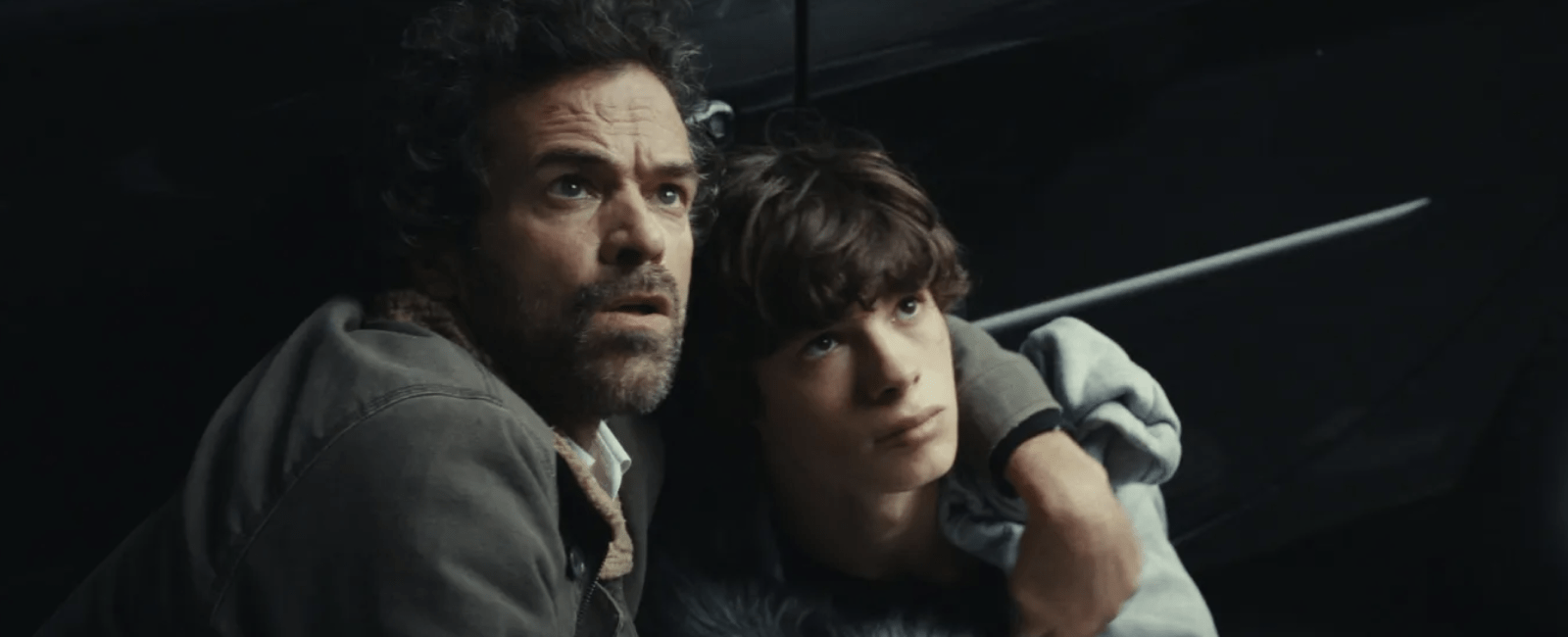

« CONAN » BY BERTRAND MANDICO IS PRESENTED AT THE QUINZAINE DES CINÉASTES AT THE 2023 CANNES FILM FESTIVAL.

By Crash redaction

Bertrand Mandico, known for his mind-bending films, takes on Conan the Barbarian and presents a captivating new version of the story. In « Conann, » he showcases six mesmerizing scenes brought to life by different actresses. The film, featured at the Directors’ Fortnight of the 2023 Cannes Film Festival, is both grand and thought-provoking, exploring themes of time and power. It represents Mandico’s most accomplished work to date, surpassing his previous films. Through a handcrafted approach and a theatrical setting, Mandico creates an explosive and innovative experience.

On the occasion of the release of his latest film, revisit his 2019 interview with CRASH :

I’m working on the north face of my brain. Or rather the north faces of my brain. I’m shuffling between several projects, it helps me think about life with less anxiety. Taking on more projects reassures me because I can tell myself that even if I only finish one, it will be the right one. Like a feature film where I rework science fiction, another where I embrace the life of cadavers in the deep sea, a bunch of videos for an enigmatic musician, a medium-length film about vampirism in the high mountains, an exhibition of films about the end of the world, an incandescent film project with a great magic witch. And then cinematic outgrowths in a gallery, based on the idea of navels as the last oases, perhaps a video game shot in 35 mm, like Hollywood Babylon/Entrée des Fantômes, a film novel about erotomaniac stuntwomen, a film about the only vampire writer and scraps of ideas to film. Mostly film.

It’s an outline for an esoteric Western. I chose that setting as a way to leave the Earth behind, in the midst of a massive forest that goes to sleep at night. It’s about cowardice, we try to console the dead. But it’s difficult to talk about because I’m still waiting for funding. I hope the film will see a new financial ray of light.

It all started in frustration. My parents would only let me watch the start of movies, before sending me to bed after the first sequence. I was frustrated because I could still hear the sound, so I would just have to imagine what was happening. Film books people gave me, and I would always daydream over photograms. After that I had favorite films, which I always discovered through the television because I lived in the country and my only window to the film world was the sad little TV screen. I remember spending feverish afternoons at my parents’ watching television and randomly discovering the afternoon programming, including some Fellini films that left a mark on me. Later on I realized it was Juliet of the Spirits and Toby Dammit. David Lynch was also important for me. I saw Elephant Man early on, and excerpts of Eraserhead also influenced me… Lynch has accompanied me throughout my life in a way. I remember the film stock caught fire when I went to see Blue Velvet at an empty theater in a seaside resort. The film got jammed in the projector, and the heat of the light twisted and melted the film stock, which gave the film an even more violent aspect. A bit like in Donnie Darko, when Donnie goes to see Evil Dead at the theater. That has happened to me twice at theaters, and both times it was a Lynch film. For me, he’s a director who has managed to reach out through the film and burn his ideas right into my retina, he touches my eyes with his light. Then there is also a mix of David Cronenberg, Orson Welles, Vigo, Ophuls, Paradjanov… I like classics and experimental film, as well as some animated film, underground movies and genre pieces… Why choose ? Film is like one big meal, you can like the dessert just as much as the appetizers… All these films shaped me and continue to make me who I am.

Since I never had access to film equipment, it was all fantasy for me. At first I wanted to be an actor. I thought the actors decided the film, the story, the setting, the music. I was extremely naive… It seemed so inaccessible to me that I started dreaming about film by drawing and developing a visual activity, as well as devouring books, music, exhibitions and comics. I discovered visionary artists who formed my cultural foundation by tracing the connections from Basquiat to Caravaggio, Druillet to Crepax, Ballard to Stevenson, Lou Reed to Glass… And so I was dreaming about film, I heard about the Gobelins cinema animation school, where I was accepted and studied. That was the only school for animated film at the time. But soon I realized that although animation was an incredible process of illusion, it was too much of a closed world for me. I wanted a taste of working with actors and actresses. I started working on live-action film through commissioned work.

A lot of work for Arte, short animated films, a few music videos, some films on the border between corporate work and art, as well as a few eccentric ads. It was another life. (laughs) I was a bootlegger, I hijacked the commission to attempt impossible things, it didn’t last very long. I quickly wanted to focus on my own writing. But it took me a lifetime to find a decent producer. Some believed in me but couldn’t deliver, people wanted to put me in a box. That’s why I developed so many short and medium-length films, while waiting to do a feature-length on my own terms. It was killing me not to be able to film. Writing wasn’t enough.

No, it wasn’t a choice. Getting funding for features was an extremely long process, especially with one producer I was working with. I was convinced I would spend my life just writing and rewriting. I needed to film. That’s how I started doing short and medium-length films in a compulsive way, with or without money and always on film. It was a good dynamic for me. And the format inspired me as an author who only writes short stories, like my favorites Jacques Sternberg or Carver, I almost resigned myself to writing only condensed stories. Why not ? The important part is to make good films. The origins of film lie in short formats. Then I met the producer Emmanuel Chaumet and The Wild Boys got underway. I made a lot of films of relatively short duration. Some were released together in theaters, like a bouquet. My first medium-length film Boro in the Box was shown with another short at theaters in Paris. The same thing happened with Notre Dame des Hormones. And last summer there was Ultra Rêve which was paired with shorts by Yann Gonzalez, then Caroline Poggi and Jonathan Vinel, my only group experience.

Yes, welcoming the public with open arms. For example, France 2 bought in advance and broadcast my shorts, which introduced a lot of people to my work. When I was working on all the short films, I often thought about Chris Marker, who made a lot of shorts, film essays, etc. Marker was an example for me, a unique filmmaker, an iconoclast who was always ahead of his fellow directors of features. There is no standard path. I reassured myself by thinking about the inspired filmmakers who made their first feature rather late in their careers, like Robert Bresson or Maurice Pialat. The feature-length late bloomers, who are often the most enduring. (laughs) The most important thing is for a film to have a pulse, regardless of the format.

I was waiting for one to fall into my lap. Like a piece of ripe fruit when you’re having a summer nap under a tree. One producer offered me a sort of Faustian contract. He was a “prestigious” coproducer, but not really a producer. That little detail caused all my misadventures. We signed an exclusivity contract. I was writing a lot… Some of my scripts won awards, but there was always some reason not to pull the trigger. I’m fairly loyal and stubborn, so I thought things would work out in the end. Nearly a decade went by like that until I met Emmanuel Chaumet. Things moved quickly with him. The first producer took an irrational approach with me, I was like a rare bird he wanted to keep locked in a cage…

When you met Emmanuel Chaumet, did you already have the idea for The Wild Boys ?

It was one of the ideas I had in mind. I showed him an older script, but he wanted me to rewrite The Wild Boys, which I wrote in two months. Then we received the grants and nine months later we started shooting. Everything moved so quickly, the exact opposite of my previous experience. Chaumet thinks that unique production is more important than perfect writing.

I never do the same thing twice. For Notre Dame des Hormones, I wanted to make a film for Nathalie Richard and Elina Löwensohn. I imagined a mise en abyme with two actresses rehearsing for a play, and I evoked the idea of jealous desire. I started writing a nearly endless dialogue almost automatically. I kept rolling out the dialogue until a creature appeared, as defined by the characters (the slippery object of desire). Once I had that enormous section of dialogue, I started making cuts. I tightened up the story and then the images came, like flowers growing in a furrow. Ultra Pulpe was a commissioned play/performance that was supposed to be performed one time at Beaubourg. Artist duo Hippolyte Hentgen and John-John had asked several people to write a performance play on the theme of anniversaries. I associated anniversaries with science fiction, because our perceptions of the future age over time. The script was performed but I didn’t see it. I ended up taking back my booklet to adapt it to my own creative world. Together with an introduction, conclusion and a few spectacular edits, it became Ultra Pulpe. For The Wild Boys, I started doing collages and sketches of young boys in a hypersexualized jungle, like illustrations for a racy Jules Verne book. From these few sketches, I imagined the whole storyline. A real adventure tale, until the metamorphosis. It always starts with the text, and then the images follow from there. I surround myself with piles of books and films that speak to me.

Let’s call it stylized dialogue organized in a digressive way. Ultra Pulpe may be my talkiest film. It’s the opposite of Living Still Life, which is organized around an initial monologue delivered to the camera, then silence and action. I had the idea for a trilogy of short films revolving around a contaminated area. It grew out of images I saw of Chernobyl, of contaminated land, distorted film… The last chapter of the trilogy conveyed the idea of a woman who restores life, image by image, to dead animals in this diseased territory. The idea was also to push the original concept of animation to the extreme: restoring life, animating cadavers. The script fit on a single page, it’s a concept that became a film. For Boro in the Box, the idea was a dreamlike biopic about a fictional director, with a surreal and logical progression, based on an alphabet book. Imagining a film is a game I play with myself, each time the constraints I set for myself become the driving force. In that case, for example, I wanted to work on vampires while rejecting all the familiar stylistic devices and identifying features.

I saw a lot of things, but I mostly returned to the original sources. The imagery of demons before vampires, The Divine Comedy of Dante and the circles of hell… I sniff out the vampire trail even in texts where they don’t appear. I like the idea of avoiding the typical archetypes used in films, which are repeated ad nauseum. Same for science fiction. How can we do science fiction today without the same old spaceship and reactors that look like enormous cigar lighters. I hate seeing screens and phones in film. How can we renew the genre and go back to the source ? By looking back to old novels, drawings and paintings. And also by checking in with the Surrealists, who were pioneers of unbridled imagination. When I approach a genre, I try to look back to its foundations, by doing archaeology, losing myself in the twists and turns of its buried sources. I feel like a spider spinning an endless web.

Some say the treasure hunt is more important than the treasure. I make a lot of sketches and notes. People started asking me to show them, but they’re wild beasts and not very pleasant. If there is any work worth seeing, it’s my films. My photos, collages, sketches and texts are just ingredients in my cinematic kitchen. I don’t mind if people taste them, but keep in mind that they aren’t fully cooked.

I thought it was an amusing paradox to represent a fantasy version of him. Joy is a dated name that was used in a lot of cheap erotic films. I wanted to give Elina’s character a low-class filmography that still included some interesting and unsettling forms. I saw her like a Frau Fassbinder, with her look and sunglasses. That’s actually the direction I gave her : be Rainer. At the same time, she cultivated a vampiric side, a creature of the night. Everything happens at night and she tries to hold back the darkness, to bring in more light. When she embraces her muse, the blood of regret flows in her mouth. It was an indirect way of depicting a vampire. She starts to go up in smoke as the sun rises. Everything is a bit cryptic, people can understand it as they choose. I don’t like imposing a single interpretation on the viewer… And there are also the contrasts throughout the film. I find it amusing to pair high-brow references with more mundane sources, to combine Jean Cocteau with The Hulk.

Yes, the Italian pornographic comic series by Magnus. Nathalie Richard plays her with brio and class. I figured that the best thing for a necrophile would be to die so they could have orgies with the dead. The character who questioned her on the phone actually existed. He’s a Norwegian named Konstantin Raudive, who claimed to be able to question the dead on his phone. The film is loaded with subtext and buried stories, whether true or false. The discussion between J. G. Ballard and Jacques Sternberg is completely imaginary and recounted by two girls putting on makeup on a train. It also echoes the comic books by Corben – Metal Hurlant was a big influence – and I see Jean Pierre Dionnet as the André Breton of French sci-fi.

What I like about those latex creatures is that they are embodied, even though they are fake; they exist because they were filmed, edited and lit up. That’s why CGI is emotionless for me, because it feels disembodied. It’s too polished, policed and calculated. When I see light reflect on latex, or a drop of water roll across its surface, I sense life. What I like in Hennenlotter’s work is the relationship to the grotesque and to horror. He makes me think of Crumb and Guston, as well as what some contemporary artists would do later on. I’m notably thinking of Paul McCarthy and his latex masks, Mike Kelley, Tony Oursler, the Chapman brothers or Théo Mercier today. Hennenlotter’s successors can be found more easily in contemporary art than in film. Films like Society by Brian Yuzna or Street Trash are part of the same cinematic family… All these grimy, plastic images influenced a whole generation of artists, sculptors and performers. The makers behind animatronics and latex creatures worked together with the arrival of 3D special effects, notably working for artists like McCarthy. I see a strong affinity between underground horror of the late 1980s and a fascinating current of contemporary art.

It plays on other sensations. I like formats that deliver. I like when you can really tell that an image is 3D. Don’t hide anything, otherwise you’re lying to the audience. But latex creatures are making a comeback in some films, which unfortunately are reworked in post-production. There’s always a fear of looking cheap or ridiculous… I find special effects to be reassuring, it tells me the film was produced and so it has an even bigger impact on me. That’s why I do everything on set – all the effects – by using hybrid techniques. When I shoot, the film has the last word, as it swallows up everything with its chemicals and silver particles. Everyone is concentrated when the film is rolling – technicians and actors are in osmosis.

I couldn’t, since I make too much noise. I like to rework the sound entirely using all sorts of contemporary tools, mixing sound and high-tech… We tinker with the sound until we achieve a sonic river that adds density to the image. That way the actors can also free themselves from the constraints of speech. When they come back for the post-synchronization, they always fall back on their feet like cats. I generally have them speak softer, and sometimes I give them contradictory directions. Decoupling the image and sound gives me more control over the whole.

I use techniques that have been around for a long time, but I take them even further. Superimposition, which consists in rewinding the film and reshooting over the same film stock, before developing it, which forces you to imagine how the different layers will interact. In The Wild Boys, all the superimposition you see was done directly on the film, almost blindly. It’s like a game or a rite. Everything that happens with this process is interesting. I also use rear projection, where I place a translucid screen behind the actors and project a pre-filmed image, which may be a classic landscape or gifs re-filmed in an aquarium, for example. You end up having no idea what you are looking at anymore. And then there is also matte painting, which consists in placing a pane of glass in front of the camera with a decor painted or printed onto it. I did that for The Wild Boys, except I used translucid photocopies of things like boats, for example. All these processes generally leave the people I work with in a cold sweat. It’s make or break. I like to question my perception of the image, every time, question my relationship to the narrative. I question myself and I question film, so I never forget how lucky I am to be able to film. It’s my way of pinching myself to make sure I’m not dreaming… I play with the form, without neglecting the story. I can’t work in total abstraction. It’s funny, I shot a little film in New York, which was made on the fly, in 16 millimeter with Elina Löwensohn and David Patrick Kelly, one of the actors from Twin Peaks. It resonates with Hennenlotter’s films, there is an intestinal creature that wants to live its own life out in the open. Anyway, I was thinking of him when I shot it, and George Kuchar, too.

The virgin sacrifice. King Kong created a sort of cinematic template, with the half-naked heroine hanging from a rock as the beast arrives. Ever since then, we haven’t stopped sacrificing young women, feeding them to beasts or blades. The idea of fresh meat for the slaughter is an archetype of the genre, which is played out endlessly. I’m interested in the questions an actress may raise through her character, the realization of what she represents for the audience. I also worked more directly on the theme of “ artistic menopause ” – as we called it in Notre Dame des Hormones with Nathalie and Elina – the moment in an actress’s career when she realizes she is no longer in high demand, when she starts getting more proposals for secondary, less central parts… In Ultra Pulpe, there are the young women who anticipate this moment by exorcising their own aging process.

Drawing on old films for their narrative intricacies, inspiring imagery or powerful emotions, yes. But when it comes to representations of women or sexuality, many films have become obsolete… It’s impossible to follow the same frameworks today… It’s essential to question the era, but not necessarily in a literal way, metaphor blends the sands of time. I like the idea of borderless, timeless film, with a distinct form and production. Just because you are a hard worker doesn’t mean you can’t be a formalist. Aestheticism is simply a choice of words. That’s why I have trouble with films that have no particular style, at all… I think you have to pull every lever when making a film : music, sound, image, actors. You can’t rest on your laurels and leave everything else to chance.

I don’t like the idea of promoting messages, because that makes for overly serious films. It keeps me from thinking for myself. I’m not a moralizing filmmaker. I prefer the winding path of uncertainty. I was recently listening to an interview with Blutch, he was saying that he could never be a political cartoonist, because for him, political cartoonists take a moral point of view; the pose of the one who holds the truth. What he said resonated with the way I approach film. I think you always need to question, inebriate, unsettle, charm, but never answer.

I see them more as questions. When someone asks me why I filmed a rape scene in The Wild Boys, I tell them that it was to end rape. There is no complacency in it, the rapist is punished at the source of the problem because they lose their genitals during the act. And I create a certain distance, by having a male actor play the young woman, with sex parts that are obviously artificial. It’s like an exorcism rite. It’s also a problem for some viewers, because the gender transformation process is so convoluted. Girls play boys and when the boys become girls, in their minds they are still boys, knowing full well that they have to play girls, while staying themselves… I’m interested in this disorienting moment of refusing binaries, like a whirlwind. I’ve heard a lot of touching accounts from young people who identify with the film in terms of their own sexual questioning. They come from all over the world, from Japan to Chile, and it’s moving to hear their stories.

When you get a taste of someone’s talent and you get them to embody a specific character, you suddenly want to lead them in the opposite direction, over and over again. It makes you want to keep acting and continue exploring. When I work with a new actor or actress, we have to sniff each other out, we need time for trust to develop. I like actors who are self-confident. Since I’m not trying to make it look like a documentary reality, I pay attention to the way actors appropriate dialogue and character. I also love the musicality of acting. I’m fascinated by the techniques employed by actors. Silencing actors to represent the truth of everyday people is not my concern. My truth is film. I try to be loyal to my actresses, but I like the idea of expanding the circle every time.

Yes, certain actresses have said they want to work with me. I’m always very flattered, and if it seems possible, then I will gladly work with them. Since I do my own framing, I’m the first viewer of my films. I keep my eye riveted to the camera, which makes all the difference between someone who shoots in digital and someone who shoots on film. When I film someone, I dive into their acting, and since I’m so porous, the alchemy happens right away. Acting technique and lighting go into it, but the final decision when I have to pick an actor is completely irrational. I do screen tests with actresses who have so much talent it’s hard to believe. I need to be mesmerized by an actor and believe in them.

Yes, it’s a collection I suggested to Elina. We’re trying to do a film a year, often with no funding, just help from some of the people in our circles. Always shot on film. Every time I take a new angle by proposing a strange character in an equally strange situation, and I try out new things. Over the years, it’s my vision of her that changes. I always try to surprise her with a new proposal, it’s like a game. I remember proposing an astonishing role, but she thought I was going too far. My idea was for her to play an inert corpse while a bunch of actors shuffled by her bedside throughout the film. It’s strange for an actor to do nothing during a scene while everyone else does all the work. (laughs) But she was right, the idea is too absurd for an actress.

The Wild Boys wrapped up its post-production in June and I knew the film was going to Venice. So that summer, I needed to shoot something in the meantime. Calypso Valois asked me to direct her music video and gave me carte blanche. I thought she was inspired and had an excellent film culture, so I wanted to give it a shot. Then Kompromat contacted me last summer, and I love their music. I suggested creating a world of car accidents and demons, a world I flirted with for the trailer of FIFIB. Music videos are interesting, it’s always an impossible gamble for me, since I’m so used to doing my own sound. I’m also an avid music listener on every platform and I’m always on the lookout for new songs to listen to.

When I signed up for Facebook, I had no idea what to post. I didn’t want to write comments or do any self-promotion, I wanted it to be a creative tool. I started using Facebook like a blog. I work on collages of edited images and ghostly VHS images. I started collecting images all over Tumblr, editing them and mixing them to create superimpositions. Now I post them like stills from imaginary films. But it’s all so time-consuming. (laughs) Stéphane Blanquet recently contacted me to publish my digital collages in two collections published by Les Crocs Electriques. I also reworked the collages by integrating them into gifs to create a projection for a Butoh performance by Yoko Higashi, in connection with last year’s exhibition “ Ghosts and Hells : The Underworld in Asian Art ” at Quai Branly. The images are from a ghost film that I’m shooting slowly over time.

Interview : Alice Butterlin

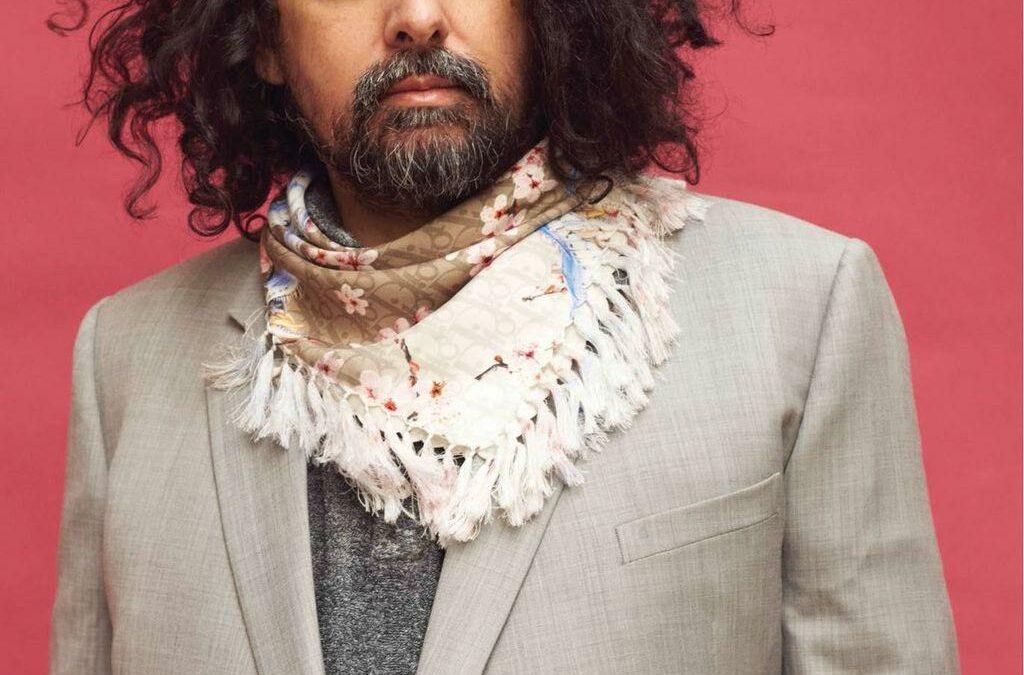

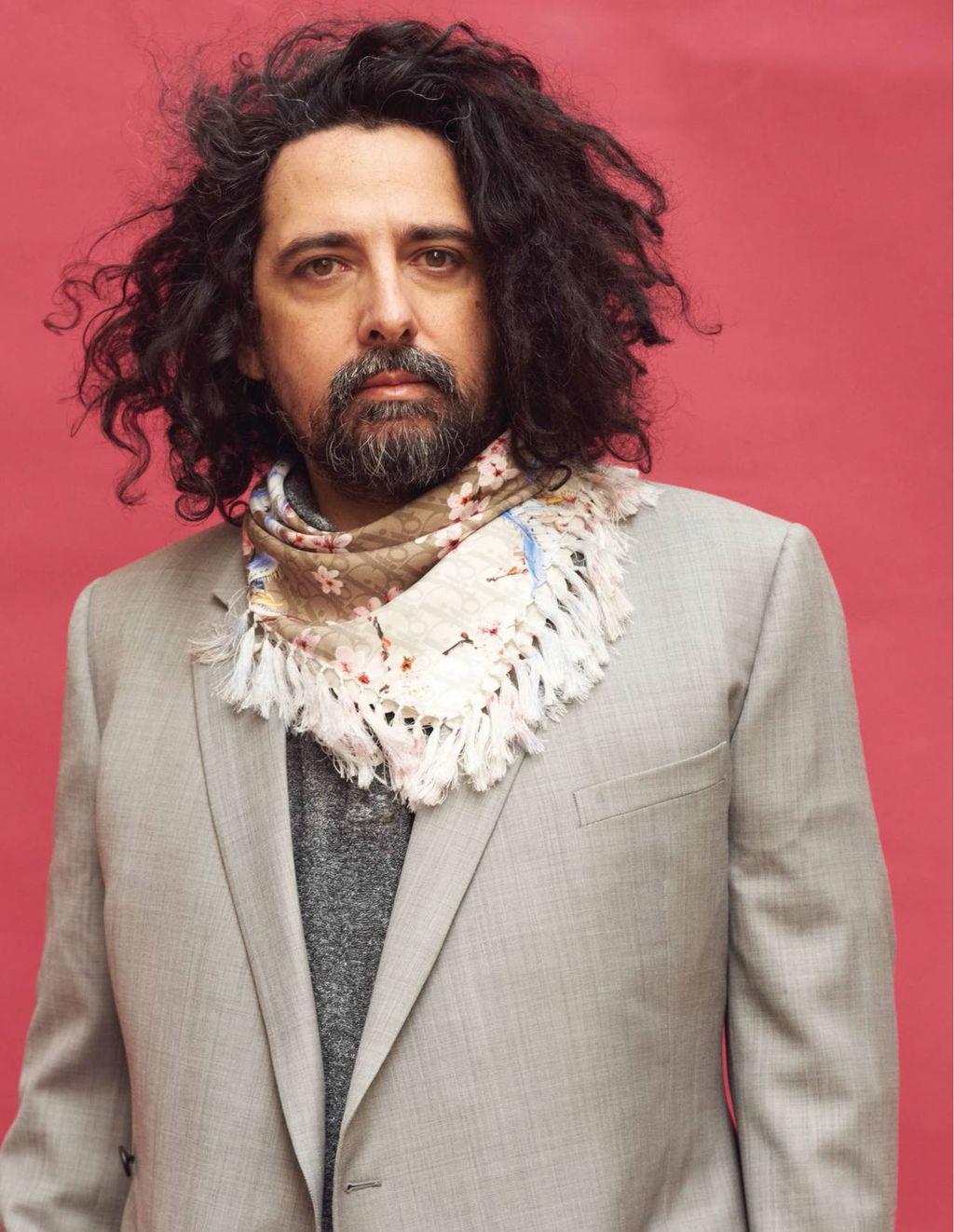

Photographer : Bertrand Jeannot

Stylist : Armelle Leturcq

Make up : Jennifer Le Corre using laura mercier and nars @Atomo Management

Hair : Chiao Chenet using Dyson hair

@Atomo Management

Stylist assistant : Pauline Grosjean