DANIEL BUREN ON MONUMENTA

By Crash redaction

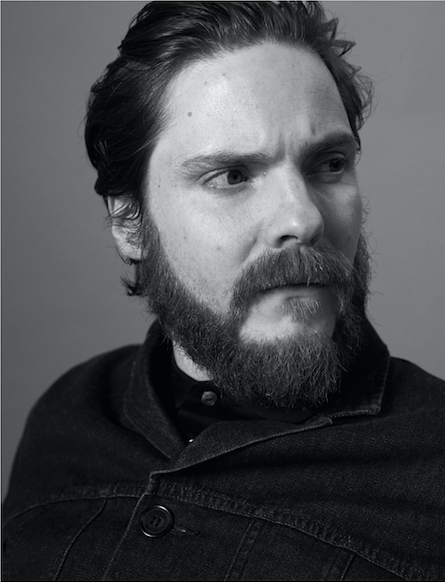

DANIEL BUREN INTERVIEW ON MONUMENTA: A LIVING EMBLEM OF FRENCH CONCEPTUAL ART, DANIEL BUREN IS TAKING OVER THE GRAND PALAIS FOR MONUMENTA 2012. IT’S AN UNDERTAKING OF MASSIVE PROPORTIONS THAT DECONSTRUCTS AND RECONFIGURES THE GRAND PALAIS IN ORDER TO QUESTION THE POLITICAL ASPECTS OF PUBLIC SPACE AND ARCHITECTURE. FOR CRASH, HE OFFERED A RADICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE DOMINANT SYSTEM IN TODAY’S ART WORLD AND THE CHANGES TAKING PLACE: THE KIND OF MEDITATION WE’VE COME TO KNOW HIM FOR…

Interview by Lise Guéhenneux

The Grand Palais is like an architectural object with a high symbolic and historic value. How do you plan to treat it for Monumenta?

It’s the biggest glass canopy in Europe that’s still in use today. It’s a hulking mass with spectacular qualities and one defect, which all got me thinking immediately about what I might try to do there. The beauty comes from light as it’s transformed by the canopy, which covers the building in stunning ironwork and juts into the sky like a balloon. Wherever you are inside, you never see anything taller than the canopy: neither trees, nor neighboring buildings, and not even the Eiffel Tower in the distance. The walls are as high as a typical Paris apartment building, but, from underneath, the vast nave and dome look like a transparent balloon hugged by the sky. That’s what got me interested in working on the building. But the structural and visual beauty is also a trap, because you can’t ignore it. And the site’s history is equally intimidating. When you look at the photos, your jaw drops when you see how many crazy set-ups have been invented to exhibit airplanes, cars, and all sorts of things. So that’s what jumps right out at you and it’s what I used to find a basic theme: light and this huge mass of air. I wanted to find out how I could place the accent on all this air in the building, which you don’t get in a museum. The Grand Palais is without exception the only space of this size in the world where artists are given the chance to do something big.

So what is its defect?

The main entrance is in the wrong spot. It brings you immediately under the dome and right into the choir: there’s no build-up. It’s almost like an architectural mistake, like if church entrances opened into the choir and not the nave. Essentially, it’s the same design as a cathedral, except with an arm cut off where the entrance is. It’s all very negative, along with the bourgeois, neoclassical façade which is pompous and grandiose – the worst the Third Republic had to offer. And this external shell hides what’s inside: an interior that was extremely radical for the time.

Were you able to move the entrance?

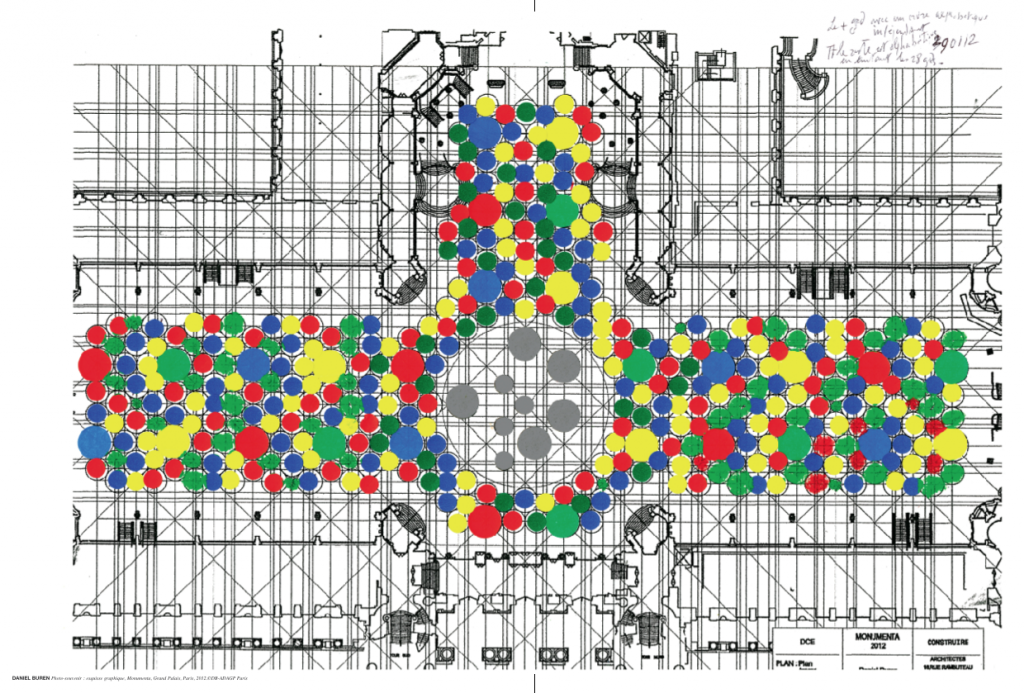

We changed everything: that was my precondition for working on Monumenta. Otherwise it would have been too great a handicap. But everyone went along with it and I was able to find a solution. Visitors will use the northern entrance, which is the least visible entrance located near the Champs Elysées-Clémenceau metro station and the police station. We’re going to use a kind of portico to make it more evident. On the square just outside the entrance we’re going to put the ticket stand, which will be based on the design used inside the building, along with a system of arrows on the ground to make waiting in line under the trees a more pleasant experience. The visual aspect comes with the arrows on the ground—maybe it will look like a crosswalk—and the low-hung entrance, so the exhibit will already start outside. But the colors won’t clash with the Grand Palais: everything outside will be black and white. Along the sidewalk I’m going to build a sort of boxed-in corridor, with a low ceiling but still comfortable, and only one string of light on the ground to make it appear even longer. So you’ll feel kind of lost in this 4 x 4 meter tunnel without knowing what’s going on at the end, where you’ll just see a box of light. And after following the path on the ground the corridor will open up into the massive nave. The idea is to give some orientation and highlight the contrast in scale between inside and outside. Finally, the nave will be completely covered with circles based on a design from a 10th century Arab mathematician. We used the design for the paving and the walls with five relatively large circles, ranging from 2 to 7 meters in size, each one tangential to the next.

So you based a lot of your work on the sky and weather in kind of a psychedelic way?

Originally, my idea was to capture the light coming in by placing color filters on the canopy, but it just wasn’t possible with the surface, height, and short preparation time. So I found another way to trap light and color against a 2.65 meter carpet on the ground. Then, just under the dome, there will be a big empty space measuring 38 meters across, decorated only by circles that mimic the design of the ceiling and topped with mirrors to reflect things you wouldn’t otherwise see. Up top, the entire dome will be covered with filters of a single color that will project down on the circles when the sun hits them.

So you didn’t have the color pattern in mind from the beginning?

I did, because I always arrange colors in alphabetical order. It’s part of my theory.

What is this theory?

It’s a simple way to get around composition! Take any four colors: in French, they’ll have a certain order from A to Z, and in German a different order. So ordering color alphabetically gives it something that will be specific to each language and each country. This kind of “composition” doesn’t come from me, but from something I take from the outside world. And here it goes even farther because we used a very small color spectrum.

But the choice still comes back to you?

Ever since I first started out, color has been one of the things that have interested me the most and that I’ve tried to approach in a new way. The way I use it depends on the country I’m working in or a limited access to materials. Like when I started doing striped walls in the US, I never used white and red stripes to avoid any association with the American flag. In Japan I avoid black and white or black and violet together since they’re the colors of mourning. I stay away from colors that mean something in context because I don’t want to interfere with that system of meaning: so that’s the only real choice I make. Other than that I think colors carry thousands of implied meanings that escape the artist. If there’s one thing that’s hugely subjective, it’s color. It affects each person in wholly different ways. I think it’s important to show that the effect of color does not depend on an individual artist’s intention, but rather on the fact that it’s recreated by the eye of the observer. Everything else is just fancy. On the whole, abstract expressionism was a positive thing as an experiment, but we know well that a lot of composition lies behind all those colors thrown about randomly.

As an artist, you’ve done a lot of work for other artists, notably on the idea of exhibition and the status of the object. We can even talk about a before and after Buren. Critics can be very quarrelsome with you. At the same time, despite the fact that the art scene is dominated by a very strict neoliberal economy, you helped establish some things that still work today. What do you think about all this?

I belong to a generation that wanted to change the system, however naive that goal may be. Today, I think if I were the same person and only 20 years old, living and working in this system, I would launch an all-out attack. So I don’t think things have necessarily changed for the better. And if museums did end up changing a little, it’s because we started asking a lot of questions in the late 60s that younger artists are still asking today, only in a different way. Since we’re no more satisfied with the status quo today than in 1965, there’s been no progress. Especially as a French artist, I know how the system has changed since then. When I started out, the art world was a total desert. There was the museum in Saint-Étienne and the Modern Art Museum, which wasn’t that great, and the few museums around were a little musty. Nothing serious existed for young and alive art in France. Whereas in Germany, I saw all these kunsthallen where anyone and everyone could exhibit and experiment: it was something absolutely unheard-of for us in France. But the paradox is that I don’t think the barren, depressed and depressing art scene of then has gotten any better today with the plethora of so-called open, permissive things we have now, at a time when a lot more money is changing hands over artworks. We went from too little to too much!

Places like the Palais de Tokyo, which just opened, need a high turnover of artists to have a full schedule of events, but there also has to be some support for production. Doesn’t this mean that soon there will be artists sponsored by private funds and others with no budget who will of course have to react to the situation?

I can’t judge objectively: I only have my opinion. If you’re talking about the question of producing works, I was part of an era when it was possible to create something with a few bucks and some change. And when we were invited by museum institutions or international exhibition organizations, the means were there, even if they were modest, for all invitees to do something without paying from their pocket. For a short time in the 60s and 70s, we used to pay artists for group exhibits, but it quickly fell out of fashion. Now we ask artists invited to major exhibitions, like Venice, Kassel, etc., to finance their work on their own. That changes everything. It’s just my opinion and I’m not pointing any fingers, but I don’t think artists are rebelling enough against this kind of thing. The rationale is always, “if I don’t exhibit here, I won’t be invited anywhere else.” But the system may turn against them in the long run.

The kind of rebellion you’re still doing today, like demanding to move the Grand Palais entrance before accepting to do Monumenta…

I’ve always thought that artists should be the ones to decide what they need. I’ve done some things that maybe were a little difficult. For example, the first time I was invited to a gallery—and maybe it’s my work that requires this kind of thing—I only accepted on the condition that they pay me. Some people say that I can ask for that kind of thing today with no problem, but they forget that I always asked for it. So I must have created something.

And what if it wasn’t possible at all?

That’s happened to me. A lot of people told me they couldn’t do it. I knew I needed it to keep going since the exhibit was made from things that would be destroyed after. Maybe the gallery couldn’t sell the work, but they have to consider us as more than mere alibis for their operations. There has to be a minimum of recognition.

What do you think of the rollback of public support and the fact that artists have to seek funding from the private sector?

In the US, which has always served as a model, museums and curators are suffering from this overdependence on the private sector even though it’s part and parcel of their culture’s philosophy. But museums are closing and we’re only exhibiting artists who are sure to have a measure of success with the public. It all started about twenty years ago in Europe, when museums still received public funds every year regardless of their financial results. Then we let the bug in by asking them to find outside money, which they weren’t allowed to do until then. And so when they did find outside money, we gave them even less. Today even institutes like the Centre Pompidou, not the least successful and certainly not the smallest, are having an impossible time organizing exhibitions. And as for new acquisitions… From being the richest modern art museum in the world upon its opening, it’s now become totally average. They have to find sponsors or raise funds among Friends of the Museum to keep acquiring works. In the Netherlands, a country that used to have magnificent museums, it’s now a catastrophe. Italy is closing everything contemporary and modern because it’s the least profitable for politicians. In France, there’s no history of private arts sponsorship, but a rich heritage of public funding… But even if private funding turns out to be better—which I doubt—it would take centuries to establish itself as effectively as the public system, but the politicians want to slash every last program. And there are much larger publically financed programs out there, like national healthcare and everything that goes along with it. In terms of art, there are countries in Europe where strong private collectors were the best option for ensuring continuous production and keeping an experienced eye on what’s happening. But that’s not the case in France. And it’s going to be a painful transition process. If things get really bad, artists will have to invent a new way of working under crushing limitations. But there’s a recent trend saying that an artist working with a golden canvas should receive more support than one working with pencil and paper. Young artists who want to fight against a certain status quo today will have to come to grips with that. And it won’t be easy. In my time, we weren’t really left out to dry because the only artists people talked about were as old as our grandfathers: it seemed normal to us, they had been working for forty years and we were just starting. Today, for many who see people of their own generation enjoying public and financial success, it’s a lot harder psychologically. You get the feeling you’ve been dumped two times over.particular set-up highlights the intangible, like height and volume, by sculpting them differently from the outside, for example.

Interview from Crash #60