INTERVIEW OF CHRISTIAN BOLTANSKI

By Stephanie Bui

Major artist Christian Boltanski died on wednesday july 14th 2021 at age 76. Our Prayers are with his family and friends.

Rediscover our interview of Christian Boltanski.

Centered around the intricately woven themes of life and death, the artworks of Christian Boltanski keep withstanding the test of time by exhibiting across the world endlessly since several decades. As he is currently coming back to Marian Goodman Library where he presents a project on “Saynètes comiques, ” a series of works he made in 1974, in addition to a presentation of photographs and artist’s books from January 12th to February 17th, we share our meeting with the artist from our archives crash issue 74. Marian Goodman Gallery was then celebrating its 20th anniversary in Paris by inviting the artist to present a solo exhibition. Described by the artist as more “luminous” than his previous shows, faire-part invites the viewer to take part in a meditative experience, full of olfactory and auditory sensations that illustrate the mystical artist’s conception of total art. From birth to death, Christian Boltanski takes us along the road of life, probing the question of destiny through a possible flight into the infinite.

Faire-part is an exhibition that can be seen as a single work organized as a journey. tell us about this journey presented at Marian goodman.

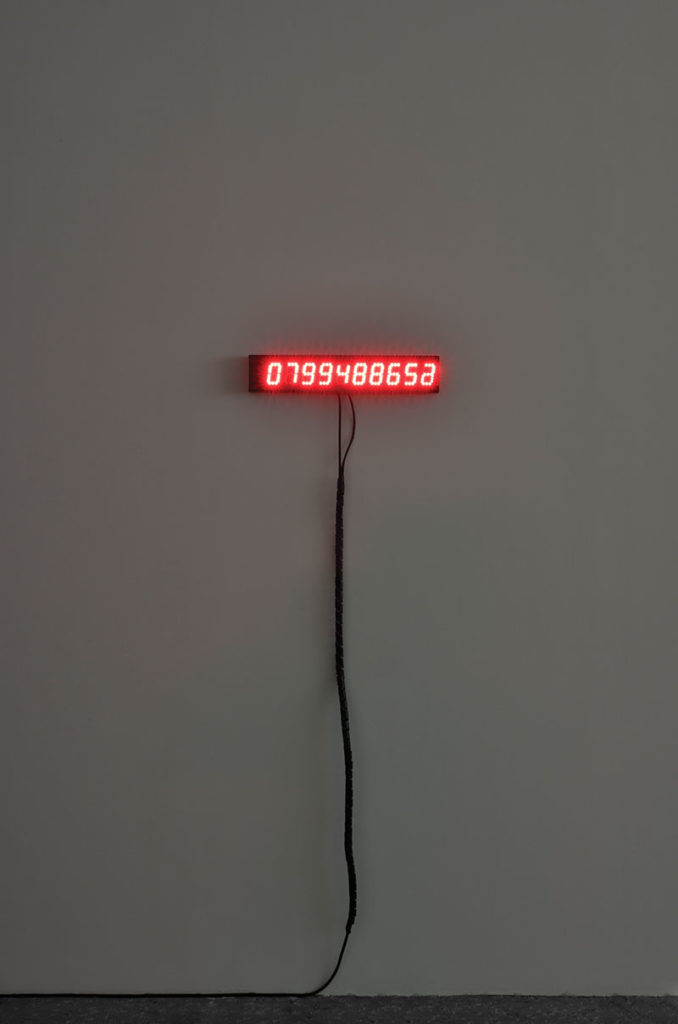

At first, the passage of time is evoked by a labyrinth of veils suspended from the ceiling and printed with the faces of young women. These women later appear on other veils in the exhibition, though this time their faces have aged. La traversée de la vie reprises a 1971 work that used a photo from Album des Photos de la famille D., dating from the postwar period. I also represented myself both very young and very old in the entre-temps print. Afterwards, the passage of time is mentioned explicitly in the diptych Départ-Arrivée. On the lower floor, and the descent to this level is intentional, the passage of time becomes quantified in Dernières secondes, which features two counters measuring in seconds the duration of my life and the life of the gallery’s youngest employee. These counters will stop when our lives end. They underline the fact that seconds pass inexorably, that you have already lost an hour of your life by coming here, and that death is always encroaching on life through the ugliness and decay indicated by the bed of cut flowers on the floor. And then at the end there comes a flight to the desert with the video projection, Animitas, a single shot filmed over 14 hours and showing the evolution of the sky from one hour to the next. the video also shows the landscape at sunset.

The exhibition’s final destination is the Atacama Desert in Chile. why is this place so important to you?

It’s a stunning place: the light is intense, it’s the driest spot on earth, and it’s the best spot on the planet to observe the sky. All these stars are represented in this work by hundreds of tiny bells mapping the exact configuration of the sky on the day I was born, as recorded by science. The symbols are fairly simple: departure – arrival, and perhaps arrival, then departure to the stars. I’m not religious, but this is an incredibly mystical place. you can feel the presence of the infinite in an unimaginable way. I think the exhibition is relatively optimistic. And even if I’m not a believer, the story refers to the idea of departing into heaven. that’s why i mention the words departure – arrival and arrival – departure. The decaying of life represented by the cut flowers is just one period. Thinking beings other than us must be out there; at least a sort of presence. I’m referring to that idea of dissolving into the universe. In the Atacama desert, you can truly feel the concept of the infinite that I wanted to transcribe here. Maybe it’s pretentious, but the idea is to be alone with the work for a long period of time in order to live a personal experience full of visual, olfactory, and auditory sensations. Now to get really, really pretentious: for the past few years i’ve been interested in what’s known as total art. The important thing for me is not to place yourself in front of something else, but to get inside, to plunge into the work.you have to forget yourself.

Tiny bells are attached to the plexiglas panels, adding an auditory dimension that significantly enhances the meditative experience.

The plexiglas panels function as Japanese wind chimes, while the tiny bells that chime with the wind symbolize a refreshing breeze and the Japanese summer. In this work they ring out like the music of the stars and the voice of floating souls.

What is your relationship to Japan?

I spend a lot of time there. It’s a country i deeply appreciate. there is a relationship to ghosts that is connected to my work. I’m interested in the creation of myths. For example, you don’t have to go to the sea of Japan to see Les Archives du Coeur on Teshima Island, though this work has become a pilgrimage site in Japan. We aren’t sure whether or not it’s a work of art. It should just exist as a myth, like the beginning of a book: “There is an island in Japan where thousands and thousands of hearts beat…” The artwork has to exist in reality so that the start of this narrative can exist as a work in itself and have meaning. But you don’t have to go to Japan to know that the artwork exists. Simply knowing that the artwork exists is what makes it exist as an artwork. Finding ways to express questions of a symbolic order – that’s what interests me. A first experience with art is similar to what we experience in a church or any other temple. I’m a painter; I don’t express things with words but with emotions. Which is the same thing.

When you filmed the Atacama Desert, you were 15 km from a small village of 60 inhabitants where you spent time talking with the Shaman. What stuck with you from this encounter?

I think there are a lot of connections between the shaman’s activity and the artist’s activity. I was born in Europe in the 20th century, but if i had been born in the desert I would have been a shaman. My way of speaking is visual; and what the shaman does is no different, even if he uses speech. If I had been born in Africa, I would have been a witchdoctor or i would have made charms – the two activities are closely related. But i was born in Europe and my language is visual, so i call myself a painter. It’s all a way to enter into the art of symbols. Visual art’s advantage over text is that it is less clear. I think each person has to take what they need from artwork. Artwork asks questions but does not give answers. It does not affirm anything. We all want to open locked doors, but i don’t think there are any keys, just the drive to look for the key. I think anyone who thinks they’ve found the key is fooling themselves.

How do you live with all these questions that continually recur in your works?

I think an artist’s life always begins in a sort of psychoanalytical trauma or drive. Well, let’s just say it’s a combination of things that explains why people become artists. It’s a bit like a journey that we talk about differently depending on our age, The people we meet, the landscapes we discover, etc. Before, all my questions about disappearance, about the act of conserving, or the impossibility of conserving things, all these questions were inside of me, but not as palpably as they are today. As you get older these questions become more pressing. As life goes by, I think we try to understand these questions a little more, and that ultimately there are very few creative periods in the life of an artist. These periods are all tied to important moments in the artist’s life. In my case, the creative periods came when i became an adult, around 24-25 years old, and when i lost my parents, between 40-45 years old, and when i started to reach old age about ten years ago. I think these periods are also tied to physical changes in the body. One artist i greatly admire is Louise Bourgeois, who never resolved her problem with her father. However, she was able to live with this problem thanks to her art. Art helps the artist live with unresolved problems. So today, for example, I think both my activity and I are happier and more relaxed. A work like Faire-part is more in harmony with the world than what I may have made 10 years ago. It resonates like a kind of personal projection. Faire- part asks a more peaceful question.

Your work refers directly to the past and the future, but what is your relationship to the present? Living in the present, or appreciating the moment as philosopher Pierre Hadot taught, is part of a spiritual quest.

Artwork sits firmly in the present because it cannot be kept indefinitely. The major pieces I produce now are later destroyed. They only live in the present. Though they may be reinterpreted or replayed later on. The configuration of Faire-part was conceived specifically for this space. I produce each work in a way that depends on the space, just as a musician might play with different orchestras at different times. It’s an extremely limited duration: just an instant. For me, the present is experience. Animitas is still in the desert. I don’t want it to be restored; little by little it will be destroyed. It goes back to the ordinary idea of vanity. Just like theater and performance, museums also offer a bodily experience that is tied to the present moment. Works can be reinterpreted and replayed. That’s the idea that is driving me today; there are two methods of transmission: Through the object or through knowledge, like in Japan where temples are notably redone every 10 years. People have the knowledge they need to rebuild them. In the same way, others may be able to redo my works one day. As long as i’m here, I’m going to play my music. If someone else plays it, it will be one of my pieces interpreted by that person. My work will then be like a musical partition, which is new each time it is played.

What do you think about the evolution of the art scene?

I think art has in fact changed a lot in the past few years.art has always been tied to money, but the concept of money has become even more important. more and more art fairs are emerging everywhere around the world. art used to be familial: a gallery, one or two critics, and 20 or so collectors were enough to form a family. now you don’t even know who your collectors are. I was lucky enough in life to work with people whom I got to know on a personal level. My collectors became my friends. I think it’s important to maintain a kind of madness and resistance against an art world that has become too organized.

How can artists resist today?

I’m a professional, but it’s still possible to avoid attending every art fair. Museums, galleries, and art schools push people to fit into a mold. You have to try to break out of this mold. The artists I like come from different fields. Some were dancers, for example. Some people live their entire lives inside the art world. But you have to work above all for yourself and in order to understand yourself: it’s a long road.

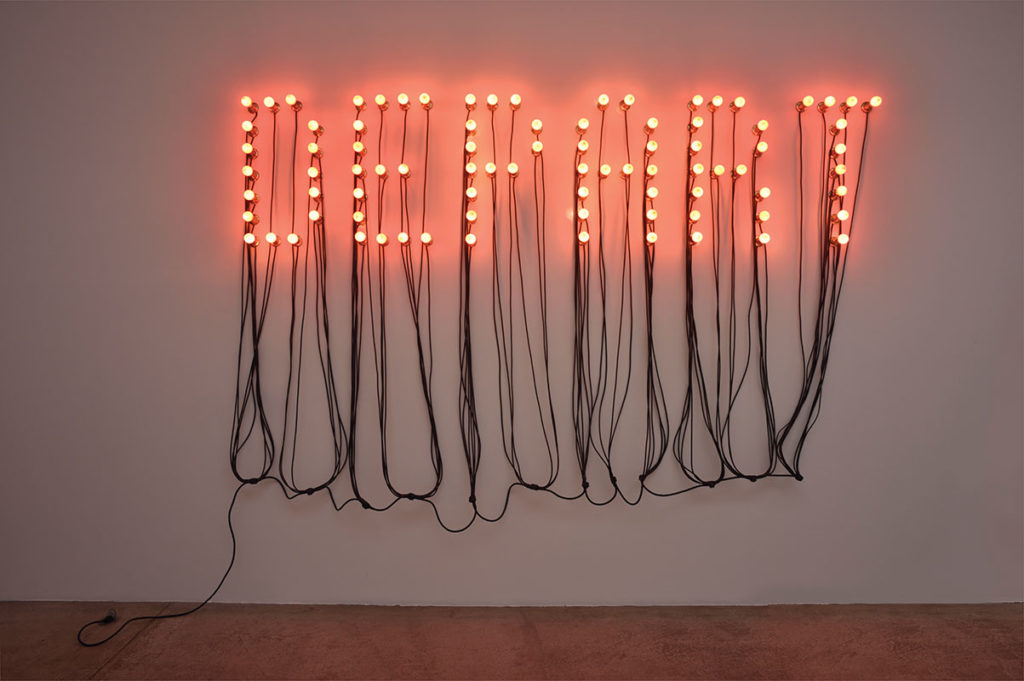

Departure – Arrival, 2015, 86 red light bulbs, 99 blue light bulbs, electric wire © Christian Boltanski

Last Seconds, 2014, led counted, electric wire © Christian Boltanski, photo © Rebecca Fanuele, courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

Animitas (Small Souls), 2015, Video projection, flowers hay, on bench © Christian Boltanski, photo © Rebecca Fanuele, courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

La traversée de la vie, 2015, 32 printed veils, 12 light bulbs, wire, electric wire © Christian Boltanski, photo © Rebecca Fanuele, courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

Meanwhile, 2015, © Christian Boltanski, photo © Rebecca Fanuele, courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

Photo : Christian Boltanski, © Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery.