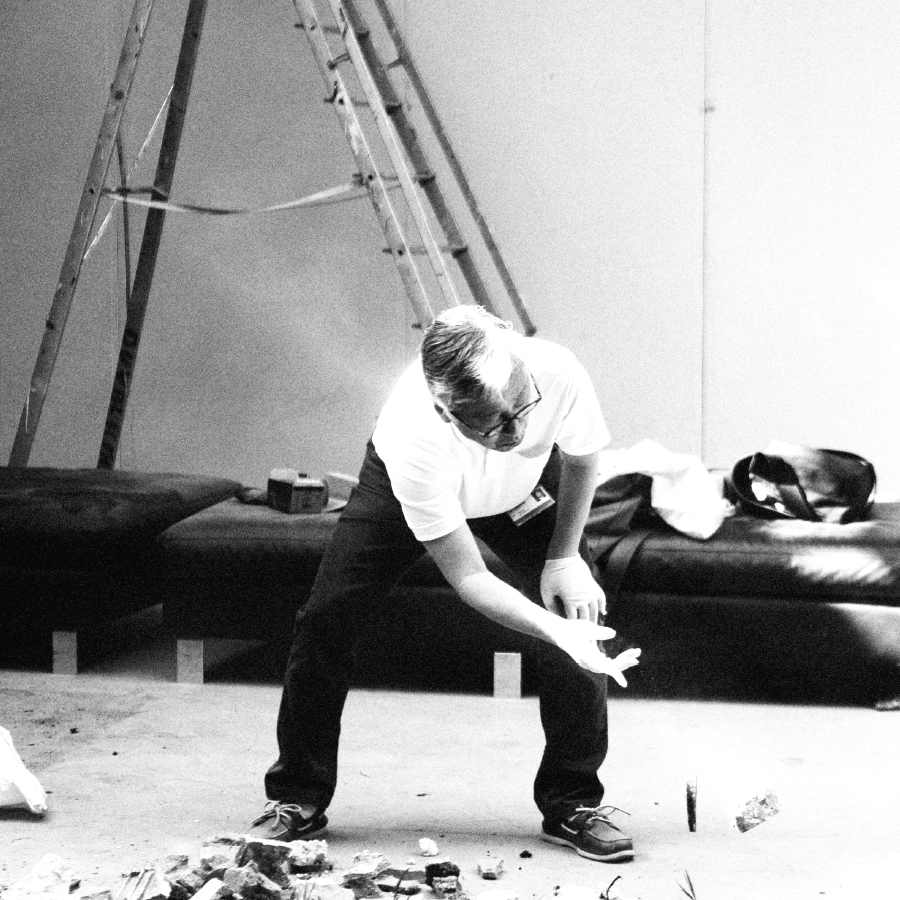

Furnification, exhibition view, courtesy of Atelier Van Lieshout

JOEP VAN LIESHOUT ON CENSORSHIP AND A WORLD GOVERNED BY TECHNOLOGY

By Anaid Demir

Is there anything worse than censorship, except self-censorship? From afar, it looks like nothing more than a stack of boxes, or a child’s game standing twelve meters high and built from crude materials. But these oversize Legos make the viewer stop and think, as do most of the works imagined by Dutch artist Joep Van Lieshout and his creative cooperative: Atelier Van Lieshout. Though they claim their “Domestikator” is a work of innocence, it was refused entry to the Tuileries Garden, where it was originally set for display from October 19-22 during the FIAC art fair. First presented to the public in 2015 during the Ruhrtriennale in Germany, the work was intended to feature on the outdoor portion of the prestigious international art fair in Paris. Instead, it joined the ever-growing list of artworks deemed too taboo for display. In that sense, it rubs shoulders with the likes of Andres Serrano’s “Piss Christ,” which was destroyed in 2011, “Tree,” McCarthy’s inflatable green Christmas tree which some prurient eyes interpreted as a butt plug, or Anish Kapoor’s artwork presented in Versailles in 2014 and nicknamed “Queen’s Vagina” by a few dirty minds. In the case of “Domestikator,” however, the public never had a chance to reject the statue, as the Louvre’s management team beat them to the punch. The staid museum preferred to spare any innocent eyes roving through the Tuileries Gardens, notably citing the children in the playgrounds. And yet, there is nothing demonstrably sexual about the installation/habitation. Though it may bear a vague resemblance to an act of coitus between a man and his dog – or a literal doggy style – the work is about as erotic as two cracker boxes taped together. Certainly of the same mind is Bernard Blistène, director of the Centre Pompidou museum, who ultimately found a home for the disturbing “Domestikator” on the square in front of the Centre Pompidou, where the artist met with us for an interview.

What inspired you to create the Domestikator?

I’ve been making a lot of objects, sculptures, mobile homes, and functional pieces of architecture. I started making more pieces related to body parts, like the Birectum or the CasAnus. The Domestikator is part of this series. With it, I thought about the meaning of domestication and humans domesticating the world. I thought about technology and ethics. I thought it would be the right piece to make to speak about these issues. I think it gives a powerful message. It makes a statement, mixing architecture, design, and art. It was a bit challenging, as well.

Were you surprised by the reactions generated by the piece? Your aim wasn’t to provoke, was it?

Yes, I was quite surprised. I thought my piece was quite innocent. To be honest, I think it’s a little bit too cartoonesque, if I should criticize it myself. It’s too “funny.” I don’t understand how anyone could find it obscene. I think there might have been other reasons why they didn’t want to expose it.

What is the “domestication” about?

It’s mostly about the ethics of new and future technologies and how it influences the world. First, domestication occurred when people started farming: having animals, growing plants… That meant they didn’t have to travel, hunt, or gather. They could stay where they were and make furniture, housing, pottery, clothing. That was the beginning of our civilization as we know it. The domestication process is an ongoing thing.

“Domos” means house in Latin. Does that have something to do with the fact that you makes living spaces?

The Industrial Revolution was a very important way for people to take control of the resources in the world. This process goes on. Today, we have a lot of new and interesting technologies: artificial intelligence, robotics… All this has a huge effect on our life. Finally, humans are being domesticated by machines.

Do you think we are in danger? What future do you see for humanity?

I think it’s a time when people will be domesticated. Data, statistics, artificial intelligence, all ruled by big companies, can control humans. It is a process that is irreversible. It will change personal freedom and the way people communicate with each other. I’m not necessarily saying it is bad, but I just want to put the emphasis on the fact that it is happening. I’m not the only one pointing it out, am I?

Do you think art can save humanity?

Basically, there is no real reason to keep humanity alive. Why are we here? Why should we keep on living? We are like parasites of the world. (laughs) I think that change is interesting, change goes extremely fast now. I’m very curious to see what will happen.

You have no idea of what we should expect from the future?

I think humanity will survive.

So you’re not pessimistic.

I’m always a little bit pessimistic and optimistic at the same time. I like the friction.

Your art is very politically engaged. For you, does art have to be engaged?

I don’t think my art is really political. If I had to compare it to political matters, I would have no idea. I don’t want my art to become a demonstration, just some kind of an idea. Art should always be very confusing, it should never give a blunt answer. It should challenge people to think for themselves.

Your art can be seen as design or architecture. Does that bother you?

Sometimes a little bit, because art is different than design. In my artworks I use design as a material, as another artist would use photography or video. Design is the language that I use. I actually don’t care what people call it.

Did you study architecture?

No, I only studied sculpture.

How did everything happen with the Centre Pompidou museum?

The Louvre decided, on the 28th of September, that it wasn’t going to happen. So we received the information very late and had to organize everything last minute. Then, one or two weeks later, Centre Pompidou told us they wanted to expose the Domestikator. Logistically it was very confusing. We had got no explanation from the Louvre; they just sent us an official letter. No communication at all, not one phone call.

They claimed they were afraid that children might be shocked by it in the Tuileries.

By two robots? (laughs) I don’t know what the fuck they’re talking about? Pardon my French. (laughs)

When you presented the Domestikator before, did you encounter similar problems?

I presented it in Bochum, in Germany, for three years in a row. Normally it’s two times bigger, but it was too complicated to have that size in Paris. The piece was used as a performance space, a bar, and a restaurant. There was never any problem, even with Muslim people. People laughed at worst.

Do you sometimes live in your sculptures?

I slept in it last night. It’s an experience.

Where will you take the Domestikator next?

It will be shown in Amsterdam in March.

Is it not a sculpture that can stay in one place forever? Does it need to travel to exist?

First it goes to Amsterdam, then there is an interest for it from another city in the Netherlands that would like to permanently install it. It is not confirmed yet.

Where are the other big pieces you made where one can live inside? Are there permanent places we can go?

They are everywhere. There are a couple museums, mostly in the Netherlands. Miuccia Prada bought a couple of large units. There is one in Belgium that represents the digestive system.

In your everyday life, are you conscious about ecology?

Yes. A lot of my work has to do with mechanisms and systems in our world, like energy. My whole studio runs with solar power, so I’m very much involved with ecology, not only in my work but also in my life.

What kind of materials do you use in general?

I use a lot of glass fiber, but also wood, steel, and aluminum.

Why do you use the name “Atelier Van Lieshout” instead of Joep Van Lieshout to credit your work?

I used to use only my name, and at the end of the 80s my work became very conceptual. I started making sculptures that expanded in size, as well as very simple furniture. Basically, I was trying to break the borders of what art is. Everyone could make my furniture because it was so simple. After that, I started making mobile homes. The idea was that I would produce my home as an artist, and be a sort of builder. I wanted to tell people I wasn’t an artist but a builder, that’s why I chose to use “Atelier Van Lieshout.”

It reminds me of the atelier of Leonard de Vinci, who was working with a crew of artists.

Nowadays, almost every artist has a studio with assistants. I heard Damien Hirst has 300 assistants. (laughs)

Who are the other people working with you?

There are about twenty people in the studio. They all come from different backgrounds: some are architects, some are designers, some are artists, some are carpenters…It’s a very diverse group. Normally, they stay in the studio for a very long time. I have some collaborators who have been working with me for twenty years now.

What are your next projects?

The piece is part of a series on retrofuturism, which asks questions about the future of the world, offering solutions on overpopulation, nutrition… I’m also interested in the futurism movement in Italy. They were also very interested in technology at their time and wanted to break from the past, to create a revolution. That was all before machines and cars were relevant – basically all the problems in the world. Now, I feel we are in a similar era. There are a lot of new technologies coming and a lot of fascism in the world, many dictators… It’s quite scary. I’m playing with the new world and this potential danger.

Domestikator, photo courtesy of Atelier Van Lieshout