JULIEN DES MONSTIERS AT THE FERME SAINT SIMEON

By Alain Berland

Alain Berland: You’ve just completed a several-week residency at the Ferme Saint Siméon, a 17th-century inn that long served as a favorite haven for painters drawn to Normandy’s unique light. As a studio-based artist used to working indoors rather than outdoors, how did you experience this residency, and how did it influence your work?

Julien Des Monstiers: I was the first artist invited by the Ferme Saint Siméon. I quickly realized that this would be a first for me in that space—but also a first for the establishment itself, which, as you can imagine, has changed a lot since the Impressionists stayed there. It was a true invitation, made possible thanks to Philippe Platel (curator of the Normandie Impressionniste festival). No one asked me to do anything specific when I arrived. But I had the timid feeling that people expected me to paint on an easel in the inn’s gardens, like Monet, Boudin, and their friends once did.

It scared me at first. Because, as you said, I usually work in a large warehouse, mostly under artificial lighting. To reassure myself, I immediately filled the studio with all the mess I’d brought with me—papers, rolls, brushes, books, paint tubes, and so on.

The studio I was given was down the street, just a few numbers away from the Ferme. It’s a sort of small, empty townhouse, and I had access to the entire ground floor. I was supposed to stay for two weeks.

Within three minutes, I realized I would spend very little time indoors—and a lot of time outside. First, because the weather was beautiful that day. But mainly because I spend the rest of the year locked away in a warehouse.

So I explored: Trouville, Honfleur of course, Le Havre most of all, and Étretat, which I had never seen before. It stunned me. Étretat is one of the most beautiful places in the world.

It’s true, this part of Normandy has a special light—silvery, almost white. The clouds look just like in the paintings, with dark undersides, as if the landscape itself were casting shadows onto them.

I drew a lot outside, with a black felt pen, in small sketchbooks. I’d occasionally stop by the studio to prepare backgrounds on sheets of paper, thinking I might paint something eventually. And I did.

I created oil paintings on paper and on small wooden boards salvaged from the hotel’s renovation site, which was on pause before the high season.

Of course, Courbet and the Impressionists came here for the light and the beauty of nature—but surely also for the view of the Le Havre estuary, with its smokestacks belching fire, the shipping containers, and the warehouses—Mordor!

Behind you: the apple trees and flowers of the Ferme. In front: Le Havre and modernity.

That’s what I’ll take with me.

It was a time for reflection outside of painting—and yet very much within the subject of painting. I felt like I was on a writer’s residency. I loved it.

AB: Did this special time give you the opportunity to reflect on how your painting has evolved, especially after twenty years of work and your recent major exhibition at the Château de Chambord?

JDM: It’s true that this time—both short and long—gave me space to reflect a bit, to come up for air. I’m a hard worker, but that’s not always the best way to solve problems in the studio.

I tend to be stubborn and tightly control my own little production line, so to speak. In a way, I even manage the loss of control—boredom, mistakes, and so on.

But who truly lets go? That almost never happens.

During the residency, I only brought materials I rarely use. It was impossible to work with the long drying times my canvases usually require.

So, I drew and I observed. Drawing is my first love, whereas painting came later—I didn’t really start until I was about 19.

Today, all my drawing practice serves my painting. I satisfy my craving for drawing within the painting itself.

It had been a long time since I’d limited myself to just a pen and a notebook.

An exhibition like the one at Château de Chambord last year is a marathon: intentions need to be more or less locked in before even beginning the first piece, deadlines must be strictly followed, and since I work alone, I had to learn to accept help.

It’s an incredible opportunity, but sometimes you feel far from pure creation—it can feel more like producing than creating.

This residency in Honfleur let me travel a bit, as they say.

I wandered around with my painter’s body, in the footsteps of Monet, Courbet, Boudin, and so many others who once stayed at this inn.

I’m not naive, and I appreciate counter-narratives, so I know they also came here because the hospitality was good, it was cheap, and they liked the booze (many letters show this—they only talk about light, booze, and food!).

When you eat well and are surrounded by friends, it’s much easier to find the sky fabulous and the landscapes enchanting, right?

Since I’m very interested in points of view in painting, I had fun trying to find where they painted from.

I didn’t leave with an irresistible urge to paint the sea or the Le Havre estuary (although…).

But I’ll hold on to this idea of perspective—not my own, but one that, through work or through painting’s sleight of hand, might just become mine.

Ferme Saint Siméon

20 Rte Adolphe Marais, 14600 Honfleur

Julien Des Monstiers

Ferme Saint Siméon

Ferme Saint Siméon

Ferme Saint Siméon

Ferme Saint Siméon

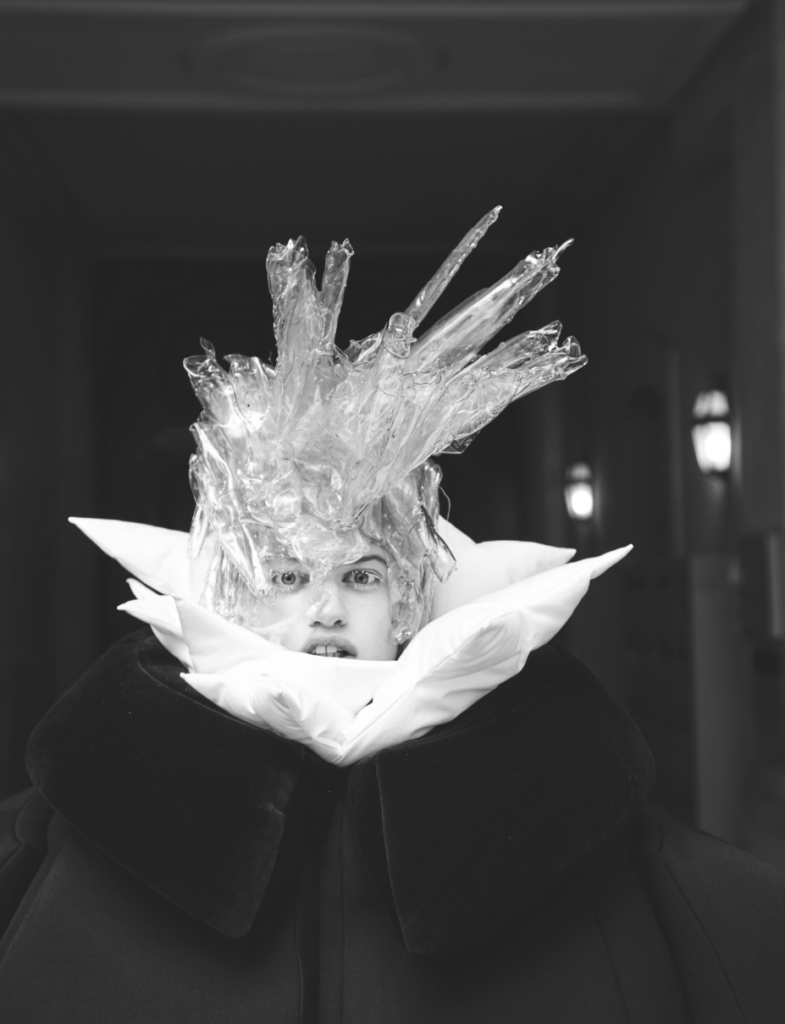

Julien Des Monstiers

Julien Des Monstiers

Julien Des Monstiers

Julien Des Monstiers

Julien Des Monstiers