MEETING: CHRISTINE MACEL

By Crash redaction

CHRISTINE MACEL, THE DISCREET BUT INFLUENTIAL HEAD OF THE CONTEMPORARY AND PROSPECTIVE DEPARTMENT OF THE CENTRE POMPIDOU FOR ALMOST 15 YEARS, SHOCKED THE ART WORLD WITH HER NOMINATION AS DIRECTOR OF THE 57TH INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION OF THE VENICE BIENNALE, SET TO OPEN IN EARLY MAY. SHE TELLS

US ABOUT HER PROJECT FOR THE BIENNALE CALLED VIVA ARTE VIVA, HER RELATIONSHIP WITH THE ARTISTS, HER STANCE ON FEMINISM AND POLITICS, AND WHY

WE CANNOT LIMIT OURSELVES TO EITHER AN AESTHETIC OR ETHICAL DEFINITION OF ART.

D.D – I began my career with you ten years ago at the Centre Pompidou as an assistant curator for the Dionysiac (2005) and Airs de Paris (2007) exhibitions. I was also there for your

first experience at the Venice Biennale as

the curator of the Belgian Pavilion in 2007 (with Eric Duyckaerts). You taught me all about

arts curating – I was studying visual and graphic arts at the time – and I can safely say that you were one of my mentors and that your influence still resonates in my practice today. I also want

to point out that, like me, an entire generation of French curators passed through your office for

an internship during their careers. You produced numerous major exhibitions at the Centre Pompidou, including Danser sa vie (2012) which you spent nearly ten years putting together,

as well as solo exhibitions that launched several international artists (Philippe Parreno, Gabriel Orozco, Xavier Veilhan, or Damien Ortega).

And yet, despite all that, you are also one of the most discreet curators in France: it seems like

you keep your distance from powerful circles and polemical debates. For some, your nomination

to head the Biennale came as a surprise –

they expected yet another “uber-curator” like your predecessor Okwui Enwezor or Adam Szymczyk at this year’s Documenta. What do you think convinced Paolo Baratta, President

of the Biennale, to pick you for this task?

What is the selection process like for an event like the Biennale? Can you tell us more about it?

C.M – Paolo Baratta makes the selection after

a period of reflection, and submits it to the Board of the Biennale. I think he makes his choice based

on his knowledge of the curator’s projects, professional reputation around the world, and

the direction he wants for the Biennale.

The project I submitted upon his request turned out to match his expectations.

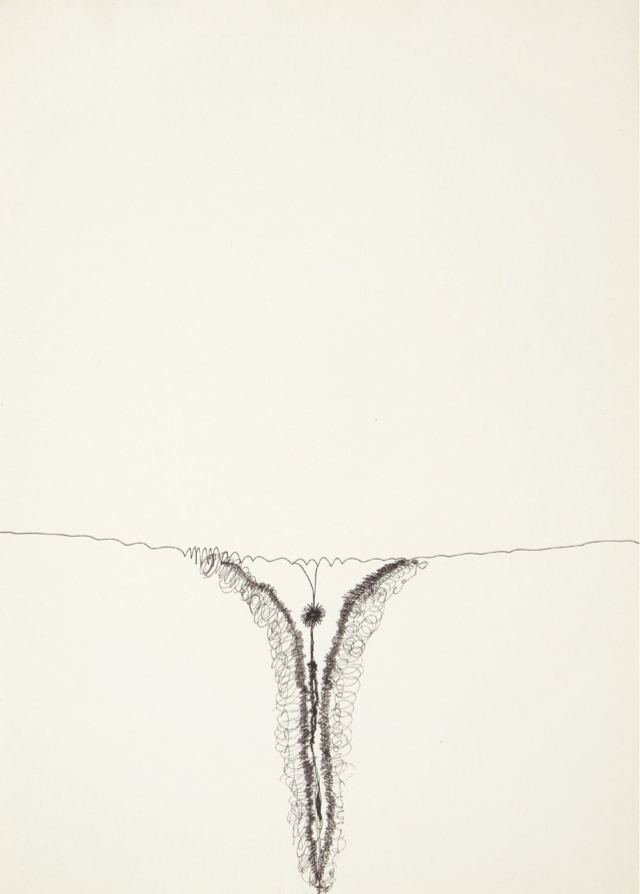

EDITH DEKYNDT One and Thousand Nights, 2016, installation view, Wiels, Brussels. Courtesy of the artist and Greta Meert Gallery, Brussels; Carl Freedman Gallery, London; Karin Guenther Gallery, Hamburg; Konrad Fischer Gallery, Berlin. Photo © Sven Laurent

D.D – The title, Viva Arte Viva, is a sort of refrain- palimpsest-poem. It has caused a lot of confusion among some professional audiences, who are accustomed to catastrophic and/or didactic titles that refer to the subjects of art (such as the

state of the world, in recent years) rather than the art itself. Your introductory text contains a lot of references to art history, notably the 1970s, to point out that artists do not need to talk about the world in literal terms to say something relevant, and that their power lies in imagining, dreaming, and creating. Do you think contemporary curators have lost that relationship to artists,to the dream and magic of art, by focusing too heavily on a type of art that functions simply as another way of formulating knowledge

or representing reality from a convenient angle?

C.M – As you know well, I don’t like to limit art to a single definition that would veer too far in either direction, aesthetic or ethical. In fact, that’s

one of the premises I notably mentioned in the Micropolitques exhibition at Le Magasin

in Grenoble. In my opinion, Felix Gonzalez-Torres is the artist who best represents this approach, which does not separate style from content

or tear apart the medium and the “message.”

Art is not a form of communication. It doesn’t convey unilateral messages. Art is an act of resistance, and not just in the political sense. As Gilles Deleuze said, a work of art is an act of resistance in itself. Or to paraphrase Malraux, art is the only thing that can resist death.In short, I don’t want to reduce art to orthodoxy. What I’ve said is that if art does not change the world, it is at least a space for reinventing it. Political realism – which we have already seen in the 19th century – is one trend in art but not the only one. I think there is a lot of enlightened false consciousness underlying these trends,to borrow a phrase from Peter Sloterdijk in his Critique of Cynical Reason. I think the choice to make art solely from an ethical or moral position conceals a sense of enlightenment that belongs above all to a bourgeoisie that knows it is bourgeois and, at the same time, feels guilty for not fighting for the principles that drive revolutions, notably freedom and equality. Moreover, politics is not always evident in art. When Mladen Stilinovic depicts the artist sleeping on the job, it’s a statement about the need to be lazy to make art, as well as a critique of labor as one of society’s fundamental values: politics is not always where we think it is.

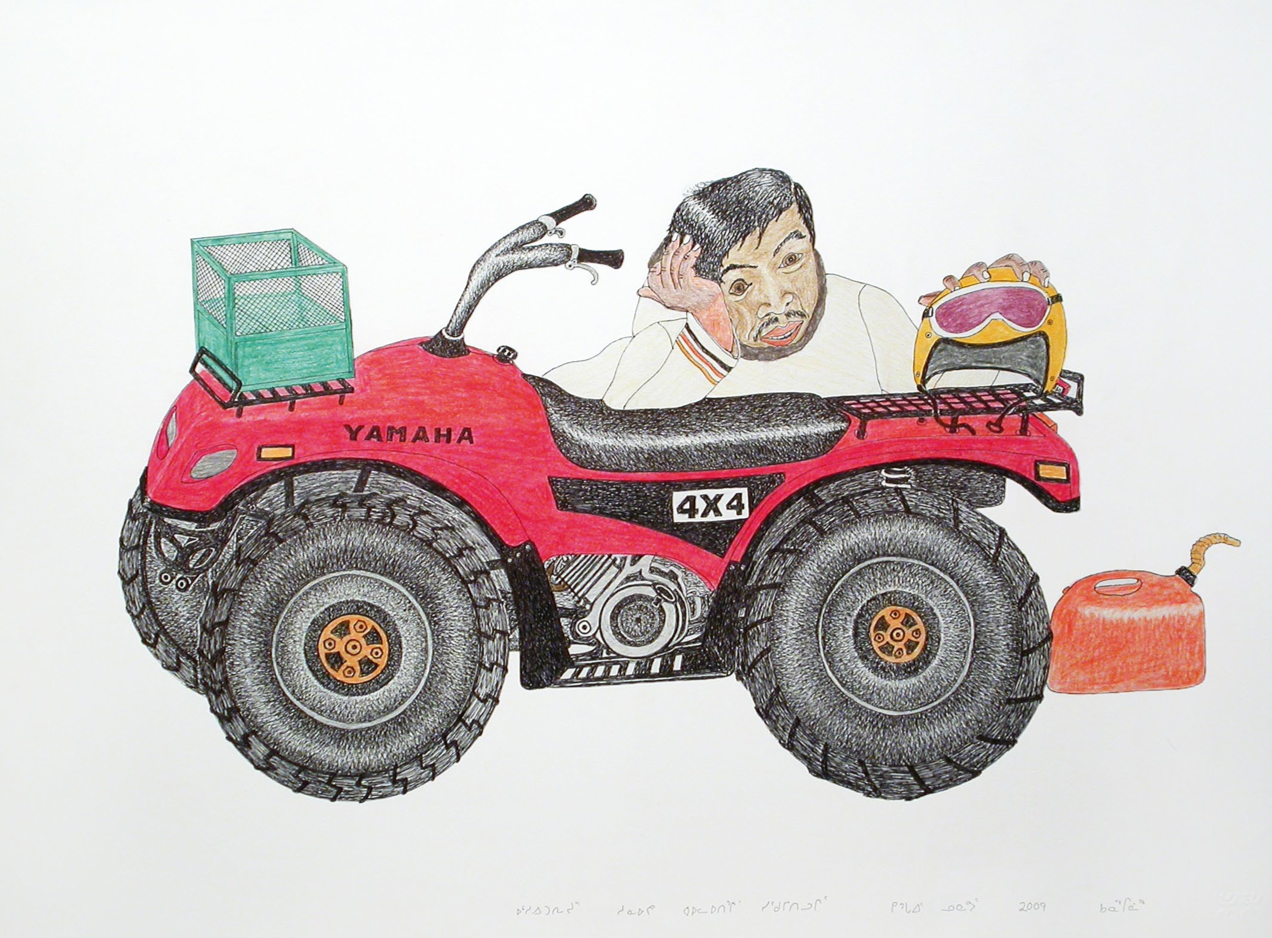

JEREMY SHAW Towards Universal Pattern Recognition (Bayfront Center Baptism, 1982) (detail), 2016, prismatic acrylic, archival photograph, chrome 38.3 x 43.3 x 16 cm, collection of National Gallery of Canada © KÖNIG GALERIE.

Photo © Trevor Good

D.D – You seem to have designed a carefully staged exhibition, which unfolds like a spectacle that must be seen in the right order to fully appreciate

the gradual increase in artistic and metaphysical power. What is it like to work in this direction at a time when the curating trend is more towards nonlinear, nonhierarchical wandering, which

we might even interpret as an attitude of deference towards the viewer or a fear of challenging the viewer at the risk of upsetting them.

C.M – It is anything but a spectacle. I choreographed the exhibition path, but viewers are free to skip chapters or read backwards as they please.

My work on Jasmin Oezcebi’s architecture aims to provide the best context for the works, the best space, and above all an optimal experience of the art on display. It is focused less on categories or hierarchies than on working closely with the artworks and artists. It’s much more complex than simply letting the artist negotiate a space on their own. It’s much more detail- oriented. In fact, the architecture is so fluid precisely because of this work. So visitors can wander without any handholding, because it is the artworks themselves that guide visitors.

D.D – Ten years later, I think it’s interesting that the “Dionysian” pavilion, a term you once dedicated to men with your Dionysiac exhibition in 2005, now celebrates women. Most women artists in the exhibition still credit you with paying special attention to this question – although it doesn’t seem to have been a priority in your practice at the time. Can you describe the thought process that led to this transformation? Do you call yourself a feminist today?

SOOKYUNG YEE Translated Vase (detail), 2016, ceramic shards, epoxy, 24K gold leaf 175x125x110cm, courtesy of the artist. Photo © Kwack Gongshin

C.M – The Dionysiac exhibition wasn’t dedicated to men, and the Dionysian Pavilion in Venice isn’t dedicated to women. The thinking that led me to the Dionysiac exhibition at the Centre Pompidou focused on the dialectic between the Dionysian and the Apollonian, or between excess and restriction, which is central to Nietzsche’s thought in the Birth of Tragedy. I invited two “women” artists to produce new works for the exhibition, which was one of the rules of its organization, but they were unable or chose not to do so. In the end, the only woman in the exhibition was Ariadne, the woman who captivates the god Dionysus and who was embodied by the actress Anne Brochet in John Bock’s film “Betonstube.” It was Dionysus’s declaration of love for Ariadne. As I remember, at the time I had written a thesis on Rebecca Horn for an exhibition featuring Sophie Calle, Nan Goldin, and Koo Jeaong-A, among others. The Dionysian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale is not dedicated to women, but to the notion of ecstasy and self-transcendence through eroticism, trance – notably religious trance – as well as dance, song, and music. It will feature works evoking female eroticism made by women, as well as works by Jeremy Shaw and Kader Attia on other subjects. This Biennale will show a lot of women artists. But I invited them for their works and not for their gender. I have always thought of art before gender. There is nothing worse for a woman than being constantly reminded that she is a woman artist or a woman curator. We don’t do that for men, do we? I’ve always been an everyday feminist. I’ve always taken concrete action for women, if only by hiring Emma Lavigne, Joanna Mytkowska, and recently Alicie Knock as conservators in my service at the Centre Pompidou. I also recruited three brilliant women to help me with the Biennale. I support talented people whom I believe in, whether they are men or women.

D.D – Let’s conclude with a slightly tough question: the Biennale features nine “trans-pavilions” (as you have called them), which is your favorite and why?

C.M – I obviously do not have a favorite. That would be like asking an author to pick a favorite chapter from their book, or a painter to cut out a fragment of their canvas. But I’m sure the audience will have fun picking their favorite Pavilion!

Interview by Dorothée Dupuis