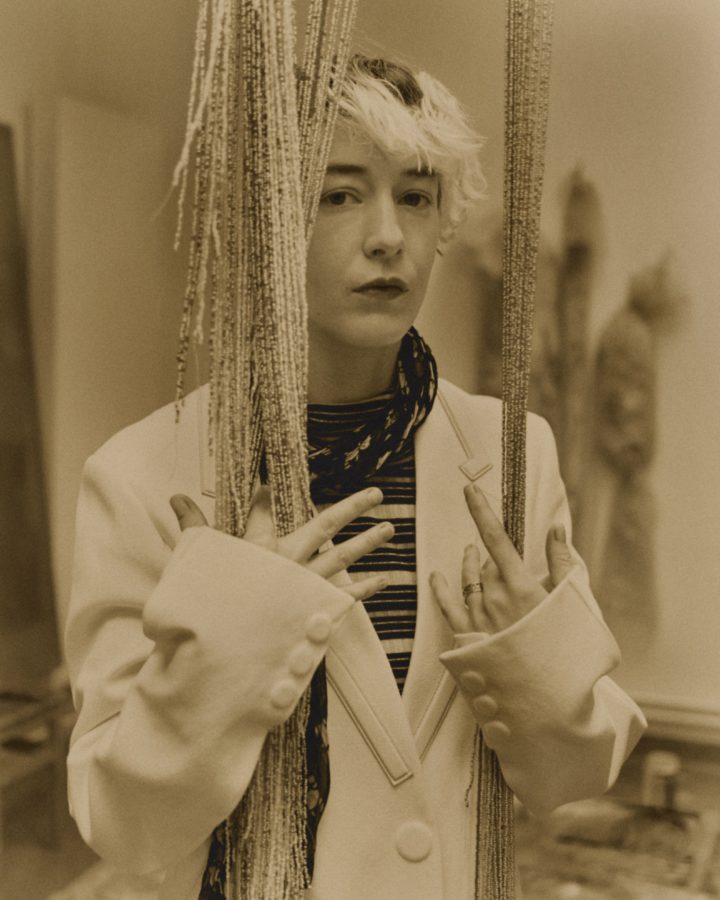

MIMOSA ECHARD WINS THE MARCEL DUCHAMP PRIZE 2022

By Lise Guéhenneux

On Monday, October 17, 2022, the jury met to choose the winner of the 2022 Marcel Duchamp Prize from among the four artists nominated for this edition: Giulia Andreani, Iván Argote, Philippe Decrauzat and Mimosa Echard. These deliberations followed a presentation of the artists by their rapporteurs, respectively: Nadia Yala Kisukidi, Kathryn Weir, Julien Fronsacq, and Jill Gasparina. The seven-member jury – Xavier Rey, Claude Bonnin, Pedro Barbosa, Cécile Debray, Elsy Lahner, Nathalie Mamane-Cohen, and Akemi Shiraha – awarded the 2022 Marcel Duchamp Prize to Mimosa Echard. Born in 1986 in Alès, she lives and works in Paris. The artist is represented by Galerie Chantal Crousel in Paris and Martina Simetti gallery in Milan.

Mimosa Echard’s practice is inspired by the creation of hybrid eco-systems where the living and the non-living, the human and the non-human coexist. Her works explore areas of contact and contamination between the organic objects and consumer items – elements that can be perceived as ambivalent or even contradictory through our cultural conventions. Lise Guéhenneux interviewed her for Crash back in the spring of 2021, during which time she had a solo exhibition at the Chantal Crousel Gallery. It was a meeting in a place infused with moving materials, during which the artist defined her space of freedom…

LG: Your work is often associated with a certain counter-culture, as well as with the figure of the witch and Michel Foucault’s notion of biopolitics. Many often note your mixed use of dead and living things. Your practice features compelling differences in scale, including small elements within larger installations that occupy a space, one which you lived in and seem to have just left: the scene of an event. It also recalls a certain Californian art that connects assemblage to performance. But what are you working on now?

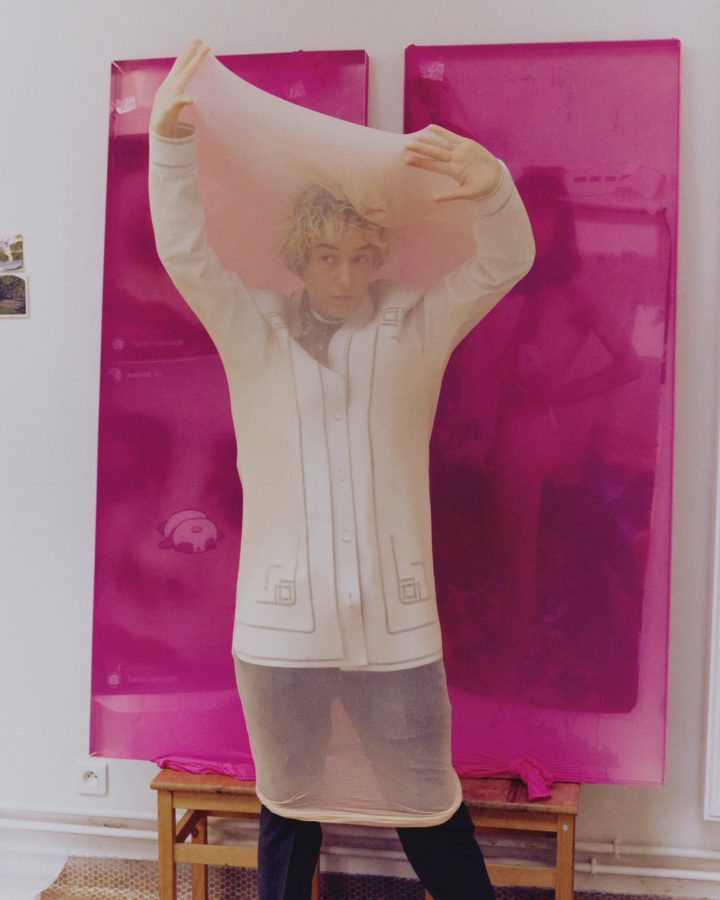

ME: At the moment I am making large « paintings » like the ones you see in my studio, where large photographic prints are covered with multiple layers of fabric, images printed on fabric, capsules, flowers, objects… There is a liquid moment in the process, when the elements intermingle and connect. It took me a while to understand how important liquidity was in my practice. For a while, I felt like it was liquid acrylic-type paint that helped me get everything to start to interact. So I had a place in the studio where I was painting. It was a little fluid, a little dirty, and things would dry and transform there. And then I used this fact to go even further in this liquidity, with water, diluted synthetic glues, latex… It’s important at some point for there to be dry pieces, liquid pieces and others in between. There is a certain structural logic inherent to the organic life of the studio. In some of my installations, I’ve developed this idea of leaving several moments that lie between these two states, between dry and wet, and there is often a relationship to the body – it still smells, like something still hot and perhaps a little disturbing. I’ve always liked that art doesn’t have to be distant or cold or dry. Can’t we imagine pieces that keep that vivid intensity that comes with liquids, fluids, blood, tears, sexual fluids, everything that moves through the body and in nearly every material around us? I’ve turned my workshop into a place where there are few categories, where waste is an object like any other.

LG: Which also means no hierarchy?

ME: Yes, it’s also true that I live in my studio and that I’m lucky enough to have a garden. There is a circulation between the bathroom, my cosmetics, garden, food, intimate items and those more specific to work. Each object exists in itself but it also transforms – there is always this idea of transition and transformation. The idea of the living organism comes from there. It’s about turning art into another body so it enters into a system of sensory relationships with matter, like with plants for example. The sexuality of plants has always fascinated me. I’ve developed a fairly obsessive and empirical knowledge of plants and erotic botanical imagery since I was a child. Moreover, when I met the biologist Pierre-Henri Gouyon, I realized that his scientific research was rooted in the same fascination for plant sexuality. He had his office in the Jardin des Plantes where he was able to show me some very old herbariums. It was incredible. In one article, he talks about a feminist research group in botany, led by Betty Lord at the University of California, which demonstrated in the 1980s that the idea of a male seed (pollen) having all the vigor and doing all the work of fertilization was a mistake. This helped me understand that we need to deconstruct our scientific idea of sexuality.

LG: So you have a deep understanding of the materials you use?

ME: Every plant I use has its own story and properties. For example, I started working with Yarrow, which can be found all over roadsides and in wastelands. Its rigid stems were used to pull the Yi-King in China. Where I come from, cultivating therapeutic plants to use for healing purposes is a strong tradition, and a friend told me about how Yarrow is used for abortions. She told me she drank so much of it that she now feels sick at the mere sight of the plant. Especially in this example, the relationship between the Chinese Book of Changes, the abortion attempt and urban wastelands creates a kind of fiction that I grasp onto and which makes me want to use the plant. I have also worked with the orchid, which survives through a rare sort of symbiosis in nature enabling its precise and elaborate sexual strategies. It feeds on a fungus that acts as a kind of food straw. This system has been artificially reconstituted by industry to turn the orchid into one of the most hybridized plants in the world today. I don’t use flowers because I find them beautiful, but instead because they point me to other stories. This type of botanical knowledge has always fascinated me. In childhood, I had a very passionate relationship with fruit trees and plants.

LG: Is this a driving force in your practice?

ME: You can certainly look at my work without thinking about that aspect, but I could never use a plant without considering this whole network of relationships. Is it possible to desire like a plant or to desire a plant? During my residency at Villa Kujoyama in Japan, I met many scientists and mycologists looking at the notion of memory in the plant world. I became interested in the myxomycete, which is an organism that is a cross between a plant, fungus and animal, and which was long thought to be just a fungus but is actually closer to an amoeba. In Japan, there is a whole culture and counter-culture of around it, including fanzines for example.

LG: Which properties of slime molds caught your attention?

ME: It’s an organism that can memorize, learn and transmit even though it has only one cell and no nervous system. It’s crazy to imagine what a single cell organism is capable of and therefore what can happen inside our own bodies with millions of cells, as well as in all living beings around us. Moreover, I’m especially interested in the slime mold because it has 720 different sexual types. The slime mold opens its membrane or not depending on the individual it comes into contact with, and it can open it to 720 different sexual types. So beyond these scientific representations, there is this idea of sexuality, of dynamics, of energies that pass through my work in some small way. This idea of symbiosis in nature, of incessant interactions, comes from studies carried out in the 1990s, such as with Lynn Margulis’s book L’Univers bactériel [“The Bacterial Universe”]. Today her research has become more mainstream and allowed us to conceive of a cultural and political world that is not binary.

LG: In your practice, you often consider tiny elements, such as fungi, plants, insects, etc., and include them within a larger system.

ME: It’s true. I have an attentive relationship with small phenomena and then I try to explore these phenomena as much as possible to make room for certain events that are going to become larger. Working on large formats enables this immersive sensory experience. This almost mental idea of the inside of the body, and how something can suddenly externalize itself to become something else.

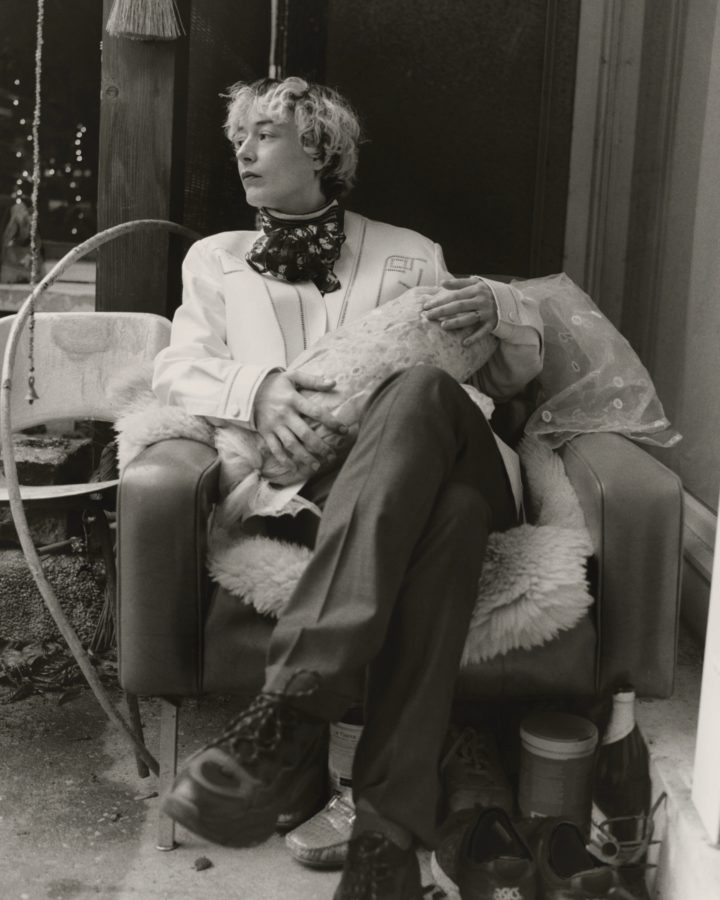

LG: So that immersion takes place within a space that remains open to surprises?

ME: Yes, in my work there is a somewhat murky moment where objects are not fully defined as sculpture, painting, or installation. In the next exhibition in March at the Chantal Crousel gallery, I’m thinking of showing these elements, which you call Polochon and I call Boudin (I don’t really know how to name these pieces), on the wall like paintings folded back on themselves, which can then fold and unfold again.

LG: Perhaps you are proposing a new type of adventure for the polochon, with this volume associated so closely with the body?

ME: Yes, I hope so! When I started these pieces, I didn’t know where I was going with it. At first there was liquid inside, sometimes clothes, personal objects, things I don’t even remember putting in there. I often use flowers that have a pigmentation power like the Clitoria or Gardenia… The plants will make sap, color the inside of the fabric membranes until everything starts to corkscrew inside these kinds of ambiguous wrappings that can twist and look like they are still wet. It’s as if, like in a fantasy films, a new weird being is going to come out of it. Another idea that can also frighten us is the notion of skin as a border, which may contain unspeakable things. I like objects that create doubt. In reality, they are fairly stable, but the transition through a moment of liquidity generates this vibrant, living sensation. The work plays on this aspect to push the notion of deconstruction even further and to stop trying to categorize everything, to reinvent new bodies that are not mere social constructs. The materials I use defy convention, especially conventions that classify certain materials as « feminine », which an artist must then justify as she must constantly do regarding her specific culture. Making art means redefining all that. In any case, art is where I feel most free. I like the idea of metamorphosis, knowing that everything can be transformed in the studio. I throw a lot of things away, and then I might pick them up again. I’m always cutting up old pieces. There is a moment of fury in the studio when I’m producing art, when all the pieces communicate with each other and get a little out of control. But during the exhibition, there is a moment of softness, of calm, of comfort even, where the pieces stay more or less in their place. Each object will then play its role of seduction, of merchandise, while remaining ambiguous and dissident.

INTERVIEW: Lise Guéhenneux

PHOTORAPHY: Motoki Mokito

STYLIST: Armelle Leturcq

View of Mimosa Echard’s studio 2021.

Embossed linen coat – FENDI

Perforated leather jacket – FENDI

Perforated leather jacket – FENDI

Perforated leather jacket – FENDI

Houndstooth patterned suit – The Kooples

Perforated leather jacket – FENDI

Perforated leather jacket – FENDI