ROLAND MOURET ON 360° FASHION

By Crash redaction

RUNNING HIS BRAND AND WORKING AS CREATIVE DIRECTOR AT ROBERT CLERGERIE, ROLAND MOURET IS A FREE SPIRIT. A FRENCH TRANSPLANT VERY SUCCESSFUL IN ENGLAND, HE PROVES THAT NO MAN IS A PROPHET IN HIS OWN COUNTRY. SHOWING HIS KEEN UNDERSTANDING OF THE WOMEN HE DRESSES, THEIR DESIRES AND THEIR REVOLUTION, HE MET WITH US TO SHARE HIS TAKE ON TODAY’S FASHION WORLD.

Living between London and Paris, how do you organize your life?

Those questions have always had a way of taking care of themselves. Since I learned my profession as I went along, without ever holding a steady job, I know how to play different roles. So it’s fairly easy for me to work three days for my company in London, one day in Paris for Robert Clergerie, then rush right back to England to my country house. The designer, the creative director and the man get on brilliantly together! Little by little, I’ve managed to partition my life, and I must say that my two hours in the Eurostar have become something of a decompression chamber for me. Lately I’ve become quite convinced that taking on more commitments actually helps me cope with the all the back and forth. My will to work also prevents me from delegating a lot of tasks out to others. It’s also a sort of contagious feeling. I like pushing the people I work with to do more on their ends, too, despite the financial crisis and all the attendant concerns we feel today.

Is this feeling of insecurity another source of motivation, something that pushes you to do more?

I’m lucky because my creativity helps me face down these anxieties. To survive in times of crisis, I think it’s essential to remain thoroughly honest in our creativity and to stay true to ourselves, on our own humble scale. And I had some experience with financial crises in the 90s. I know they are hard times, but I also know that they blow over. Times of scarcity are particularly interesting, since creativity has to work much harder to stay in step with the times. It has to be open and respond to the environment. I like juggling the unexpected events the world throws at us: acting without submitting, and creating with reality. Because whatever happens, whatever catastrophe arrives, no one ever leaves the house naked! We always throw on something or other to deal with whatever is facing us. Once you get over the superficial aspect, clothing is always representative of social realities! We always need something to cover ourselves: it’s vitally important.

Does that mean you imagine fashion in concrete terms?

I don’t think it’s possible to simply make a dress. We always have to ask: “Where is the world heading? How will our world be like tomorrow?” And we have to try to create clothing that corresponds to our changing world. And we do this every season. Women seem so complex to me that there are always a million questions to ask! My basic technique has always been folding, a system that falls somewhere between draping and origami. But that doesn’t prevent me from exploring new materials or new silhouettes each season. One thing is certain: I don’t have any conception of the ideal woman. I always begin with reality: clothing is concrete! It’s a tool for the body, for covering oneself, for concealing what we don’t want to show and accentuating what we want to show. It’s also a form of communication.

But isn’t appearance taking on too much importance today, especially for women through social media?

That is true, but I don’t think we can find any easy answers here. In fashion, at least the kind of fashion I do, clothing expresses a very precise character, something very close to the body. And to do it right, you need a minimum of self-knowledge. My clients have to look at themselves with a certain intelligence and clear perspective on their situation. Along with that, changes and new thought can take place. To me it seems like we’ve taken a step forward in that we are changing the way we think about cosmetic surgery and aging in our society. It seems like we have a growing appreciation for the passage of time. I think we’re moving away from trying to cling to a frozen image of youth, and that’s a good thing. Fixating on one thing is futile and rather ridiculous. France is one country where age is truly appreciated. There is a certain amount of respect for the way people age. We’re beginning to find beauty in it.

And you would celebrate this kind of attitude, since fashion should never become a form of alienation…

Of course! Today fashion is too often consumed like a drug. Through aggressive ad campaigns and targeted accessories, luxury tends to foster a form of addiction. It can compel people to consume without thinking, sometimes to the point of bulimia! The challenge is to find a way to maintain your honesty in this kind of environment.

And it’s a delicate balance, because we can easily fall back into uniforms: the same look, the same bag for everyone…

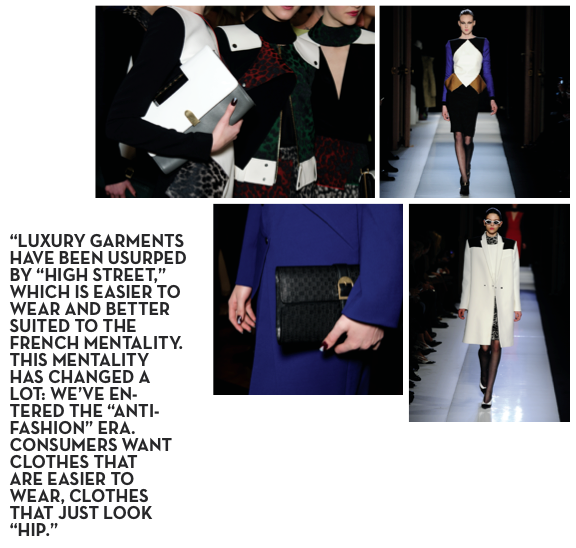

Precisely, because we are like children: we want to be part of the group. Clothing and accessories help to situate us within a group. And also within an age group. And the typical look of our times is very simple and reassuring. We don’t take too many risks. It’s a shame, because working so hard to conform can cause us miss out on who we are. Probably for that reason we might say that a bit of grandeur has disappeared from French fashion. Luxury garments have been usurped by “high street,” which is easier to wear and better suited to the French mentality. This mentality has changed a lot: we’ve entered the “anti-fashion” era. Consumers want clothes that are easier to wear, clothes that just look “hip.” This perspective on fashion developed hand in hand with the rise of accessories, which changed all the codes: with an “elegant” bag, we no longer wear “elegant” clothes. Elegance is now the prerogative of accessories. It’s funny, because in England it’s the total opposite: clothing made a comeback in the 90s. Women started wearing dresses again. Fortunately for me, because that’s what I liked making. And I think I did a lot to bring them back at the time. Anna Wintour later told me that it was one of the best ideas to have at the time for both aesthetic and economic reasons. I love freedom and creativity, but I also know they can also be accessible.

How do you manage to separate your two artistic responsibilities?

For my own brand, I always work with folds. It’s my own characteristic technique, and I use it to build my heritage and tradition. At Robert Clergerie, I’m working with someone else’s heritage. So I can push products towards a more “fashion” sensibility, since the brand is already well anchored in people’s minds. I know the Clergerie image will always be recognizable.

You have always been independent. Was this a conscious choice?

I’m very happy with my situation. I never wanted to work for a large group, since it’s entirely possible they may have just gotten rid of me after a few years. I don’t deal well with rejection. I’m sure that kind of uncertainty and suspense would have eaten away at me. And I’ve had to pass on a few wonderful opportunities for that reason. With my company, I found the independence I need. I have equal ownership rights with Simon Fuller, who was able to kick start me by helping me build my own company. And our partnership is very open: we only meet a few times a year, mostly to talk about the future of the company rather than management. That’s the kind of collaboration I like. On the day to day level, my company operates at its own pace and runs on its own management schedule. And I like to share responsibility. Within the workshop everyone is free to play a direct role in whatever we’re working on, even if tough remarks have to be made.

Why England?

I left France when I was 30, because I felt I was missing out on something. The 80s were kind of a blur: I floated along, working as a creative director here, a designer there, even a little modeling… Nothing definite, even though they were great years. But when the 90s rolled in I didn’t have the same energy, I just didn’t know what to do anymore. I wanted to do something new, I didn’t feel fulfilled. England always had a certain appeal for me: I’m enamored with the Victorian era, Dickens atmospheres, the start of the English century! My other option was New York, but I wasn’t able to get a green card. So with nothing to lose I gathered my courage and left for London. I created my brand at 36 and it was everything I wanted. During the first two years, every day seemed like a movie. It felt like my entire life was one long, exciting screenplay: a feeling I never had in Paris, except maybe at night, when everything feels a bit cinematic. And as the saying goes, no man is a prophet in his own country, and at that time, and every door was closed in France at that time. I didn’t see any future or any reason for me to stay at all. And maybe I was right, since most French designers who got their start in the 90s aren’t around anymore. Nothing new could really be done with any real sense of freedom. There was no room for creativity because the times were getting very tight and everything started to be run by money: small designers had to be happy with small products that sold fast in order to get by. I wouldn’t have been able to do it. For me it’s a tragedy to do nothing but small pieces, to have to abandon everything revolutionary and grandiose in our ideas.