ON ART AND LIGHT BY JULIO LE PARC CRASH 66

By Crash redaction

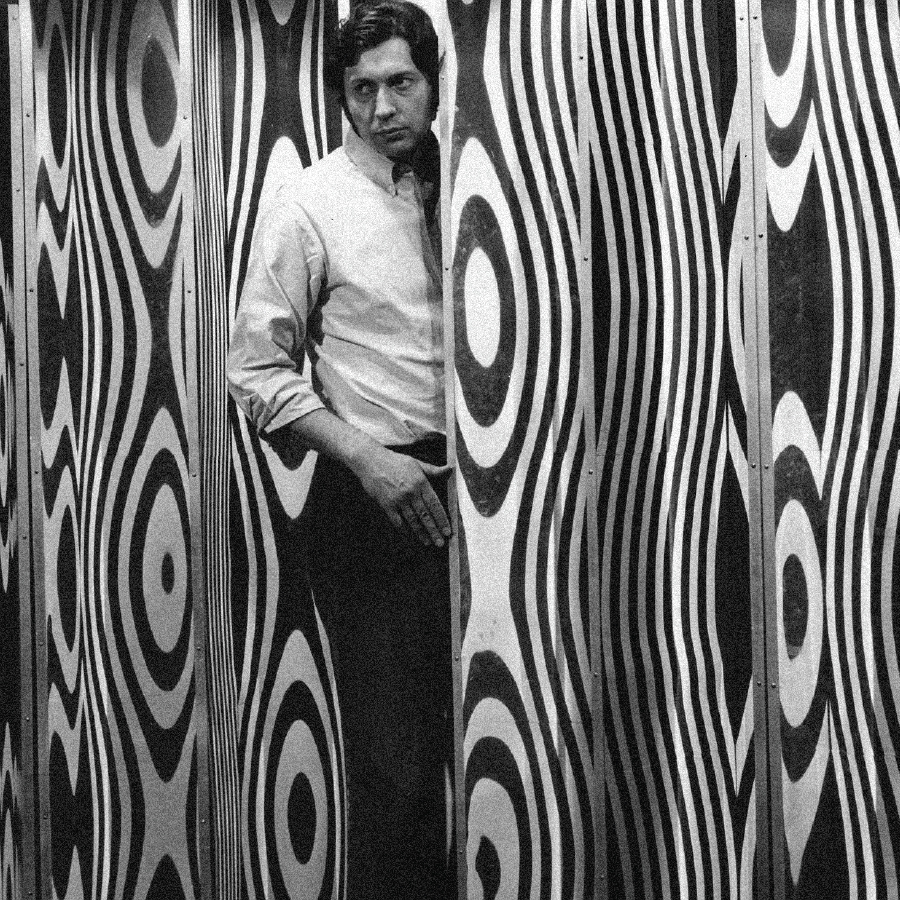

JUST MONTHS AFTER HIS RETROSPECTIVE AT THE PALAIS DE TOKYO, JULIO LE PARC, WHOSE WORK IS BOTH POLITICAL AND SURREAL, IS SEEING A FLURRY OF SUCCESS. HE MET WITH US TO TALK ABOUT HIS CHILDHOOD IN ARGENTINA, HIS ARTISTIC RESEARCH, AS WELL AS HIS CRITIQUE OF THE ART WORLD AND ITS CONSTRAINTS. ALL WITH NO DOUBLETALK AND A LOT OF HUMOR…

Tell us about your three exhibitions that just opened in Brazil in October.

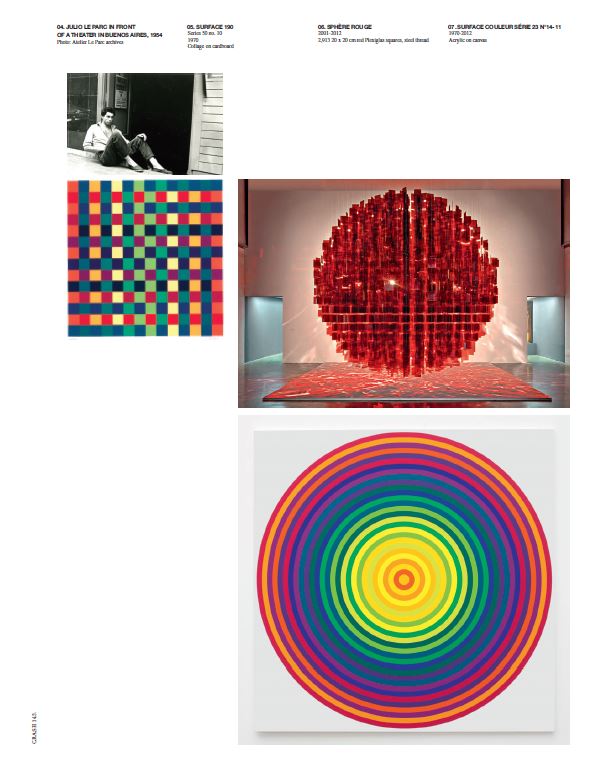

The first is at Galeria Nara roesler in sao Paulo, where I worked with curator Estrellita Brodsky to put together a selection of large-scale works. Galleries usually try to show pieces that are easier to sell. There are also a few of my sketches and gouaches. I’m not selling these, but they insisted

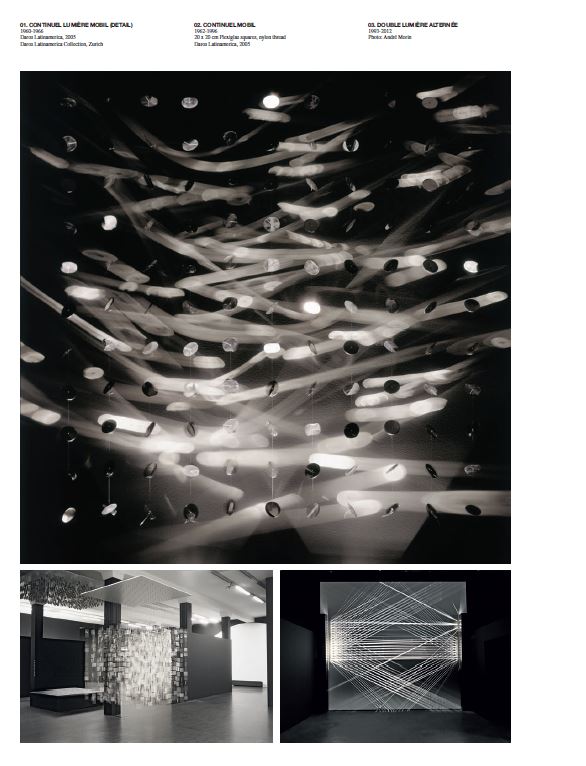

on exhibiting them to show how these pieces I did in the 1960s are related to the rest of my work. The second is in a new gallery called carbono, which is also in sao Paulo. My son Yamil curated the exhibition and presented several of my graphic works. and the third exhibition is in rio at casa Daros. It’s an enormous building with I don’t even know how many square feet. This one is a themed exhibition presenting my works dealing with light. They paid a lot of attention to space, giving each artwork a lot of room in order to present it well. In my big exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo, I added some of my research in order to create a different situation. There was a large work on the ceiling, then others on the walls. But casa Daros is even bigger, a lot bigger. and everything is black: the ceiling, the walls, the floor, everything. Then, in the middle of the room, there’s a single artwork displayed on its own. The works are more… “sanctified.”

Did any artworks or artists have a big impact on you growing up?

When I was little, I lived very far from the capital of argentina: 1,200 km to the west, near the andes. It was a tiny village, with only one asphalt street running through it. We didn’t even have running water in our house. so there weren’t many options when it came to art. No museums, no galleries, not even any television or newspapers to see images of art…

When did you know you were going to be an artist?

artist? I never thought I would become an artist. But my grade school teacher did say I was good at drawing. she told my mother she should encourage me to go into art. Later on, my mother, my brother, my sister and I went to Buenos aires. and one day we passed in front of the art academy. That’s when my mother remembered what my teacher told her. But before I could enter the academy, I had to go to a preparatory school. and to get into the prep school, I had to take an entrance exam. Well, for the exam you had to do some charcoal drawings and plaster models. so some of the art academy grads taught classes every night for anyone who wanted to take the exam. at the classes there was nothing but a bench and a model to draw. as soon as I sat down, I knew I had found what I wanted to do. I wanted to do that and nothing else. I was 14.

And you started apprenticing even though you were still so young?

I did, mostly in a leather workshop. They made ladies handbags and gloves for a store on the main road in Buenos aires. Very chic. Even there, they eventually realized I could draw. They had me draw the models and new prototypes. The head of the atelier laid the bags out on a table, and instead of taking pictures of them, I would draw them. They would call me whenever we got new products. It was a great experience and I really applied myself… It was a lot like a real job.

You were working as an apprentice and attending class at the same time?

It was complicated. We had moved outside the city, so I had to catch a train in the morning. at lunch I would make the half-hour trip back home to eat in a hurry and then head back to town to work in the atelier. after that I would walk another two kilometers for my evening classes. Evening class was a good system. There were a lot of kids who worked during the day and attended class at night. classes lasted from 7 to 11 at night more or less. after that I went home, along with a few other kids who took the train like me. I would get home, eat very late, and fall asleep right away. Then I woke up the next morning and started all over again…

So you didn’t have any leisure time?

No. That’s why I never learned to tango! all the kids in my neighborhood looked forward to saturday to go dancing. But I would just draw all day and night long. On saturdays and sundays I built landscapes with bits of wood and I would work on my straight lines and curves. We didn’t have any money, but we had a record player. We would listen to stravinsky’s Firebird over and over again. Eventually the record didn’t even play music anymore, just a lot of grinding sounds…

What did you think when you arrived in France on a scholarship in 1958?

I think the French, much like Mexicans who still show some of the pre-columbian influences, have a very strong past behind them. There was a kind of block, or weight. Movements like surrealism, Dada, cubism and Impressionism had an enormous impact on modern art. and for young artists, this past was a heavy burden. at the same time, some incredible work has gone completely forgotten. No one knew Mondrian, for example. right when I arrived I went to the Museum of Modern art to look at Mondrian works but there wasn’t a single one! The teaching at the academy was also behind the times. Whereas in argentina, a student movement with a clear political organization emerged in 1955. We occupied three art schools, chased out the directors, sent the professors home, and then called young artists from Buenos aires to teach us while we occupied the schools. There was a sense of curiosity, a need to stay informed, to break with academic teaching and learn other things. I think we were more open to the future!

Where did this freshness and curiosity come from?

argentina was a brand new country. Independence came in 1910. It was easier for people to look to the future than the past. I remember we had a female professor who came to Paris in the early 1960s to visit the art academies in Europe. We went along with her. When the director of the academy welcomed us, he said, “You need to know this isn’t a traditional school, we even talk about Impressionism here!”

Were you disappointed?

No, not disappointed. But almost immediately, I went all around Paris, to the museums, galleries, and the academy. There wasn’t anything too interesting in the galleries. The only place with anything new was the Galerie Denise rené. Living in argentina at the time, you tended to get lots of fantastic ideas. I thought I was going to find an exciting city in Paris, with all sorts of talk and discussions. But instead people were very apathetic. It was the end of something. The surrealists were still exhibiting here and there, but it was the end.

So you decided that everything was possible?

Exactly. In our talk we would say: what can we do, lowly art school graduates, in the city of art where there had been all these immensely creative people, all these artistic movements? The only option was to invest. To invest the time I had thanks to my scholarship. It was the first time since I had started studying at the art academy at 14 that I was in complete control of my days.

That’s when you created the GRAV research group with Sobrino, Garcia Rossi, Morellet, Stein and

Yvaral. What impact did collective work have on you?

We analyzed our situation and the art world from every angle: there were the salons, galleries, and other places we could exhibit… That’s also when the Biennale de Paris started. Then there were the art critics, museum directors and collectors. and all the artists worked on a very individualist basis. We wanted to change all this and not stay isolated. There were a lot of artists who had found a system they repeated endlessly, like their trademark. Whatever they did, it was art. all these thoughts influenced our group work, already in argentina with the student movement, and later in Paris with our research group. It was a way to eliminate any pretentions of becoming a great artist creating extraordinary works. We wanted to open up everything we were doing and try to produce a few collective works. We shared our ideas, experimented, researched. Other people borrowed our idea of creating a group. There was a degree of emulation.

How do you organize collective work?

Well it first started when we found a garage in the Marais neighborhood. Once we had a place, we founded our group. We cleaned it up and held our first exhibition. We could all go and work there. But actually the only one who worked there was me. Because sobrino had a space, and so did Joël stein, Yvaral inherited his father Vasarely’s atelier in arcueil, Garcia rossi went to work in Brussels, Morellet had a big house in chollet and didn’t need to come. But we still met and worked together frequently. Our relationship became more intense when we were asked to take part in the Biennale de Paris in 1963. It was gigantic, with the big entry hall and everything. We thought about what we might be able to put in there and we managed to produce something together.

You applied your critical vision to the state of the art world…

Our vision only helped us see how things were. how to change them was a completely different question. But at least we tried to suggest a few things and show that there were other possibilities. Even though, afterwards, the art world stayed the way it always was.

How did you first start working with light?

Well I didn’t wake up one day and think, “I’m going to work with light.” I did a lot drawings and gouaches with different permutations of 14 colors. The first color is yellow, then it goes to green, blue, violet, red, orange, and then orange again. I did research, and each time I noticed there were an enormous number of permutations, even with very small scales like this. I would start with 14 colors, then 14 plus 14 and eventually ended up with 20,000 variations. afterwards I thought about how I could present all the possibility I discovered in variation. I placed the 14 colors in a transparent circle. Then I made a little box that I could use to multiply the color variations. I installed a little battery-powered light bulb in order to project and turn the colors. and that’s why I started using light: so I could manipulate these permutations of color and satisfy my curiosity. Later I bought some cardboard and nylon string to build these kinds of mobiles. Then in place of cardboard I used Plexiglas. and sometimes there would be images on these bits of Plexiglas. so little by little I was putting things together. Light was playing a greater role with all the reflections. I was able to develop my work in new directions by manipulating the source of light. I tried to see what worked. It wasn’t light for light’s sake. But light helped me explore some of the passions I had. all the themes I’ve developed in my work are always open-ended. I may go back to any one of them at any moment, or explore a theme farther, or take drawings or sketches I didn’t develop, give them a new shape or mix them with other drawings and go from there… In all that, there is the theme of light and the variation of levels, permutations, the theme of instability which may be developed in a number of ways. I have never been a single-theme artist by any means. That’s one of the things the art world demands of you. Even at school. You have to create a style. Once an artist has found something, they’ll spend years just repeating the same thing. The group of Daniel Buren, Parmentier, Mosset and Toroni has understood this perfectly well. They said, “Why should we bother with variations when we can just use the same designs?” so they kept using the same designs, always repeating themselves. In my work, light is an important element. But, at bottom, this use of light is only a consequence of something else. I was never concerned with the beauty of my pieces. My concern was to move forward, to draw comparisons, to continue on…

You always work to question the role of art and the artist in society. How do you see the art world

today?

We denounced and fought against the art world and its methods. But all the decisions are made by a very small group of people. It’s not a very open world and there is very little possibility to develop new things.

Are things worse today?

Yes, I think things have gotten worse. It’s even more out of control. Rivalries between artists have grown stronger. Back then there were rivalries, but it was more like a big family: we met up, we spent time together. Now only a small number of artists, in a very artificial way, are deemed valuable. Money decides whether or not an artist is any good. All the rich variety of different artists with different ideas doesn’t count for anything. The major museums use electronic devices to count how many visitors they receive. But no one knows what any of these visitors actually thinks.

Your retrospective at the Palais de Tokyo was a big hit with visitors. What did you think of the

exhibition?

Every time I do a big exhibition like this in Europe or Latin America, there is always an immediate response from the public. They never need any explanations of my work. They connect directly with the work on display. It’s the viewers who bring the works to life. I saw how visitors responded to the Palais de Tokyo exhibition. I have no problem when the beauty of art makes people feel good. In the 1970s, along with some of the discussion in art theory and aesthetics, which was all against elitist art, certain people were also against beauty in art. Beauty was suspect. But one thing I remember about the Festival de Nancy, which was organized by Jack Lang, who would later become the French Minister of Culture, to protest what was going on in Chile, to protest Pinochet’s coup d’état in 1973, I remember I saw a Pina Bausch ballet one night. The beauty of the performance was more revolutionary than any of the revolutionary discourse going around. There are other ways to effect change than to constantly denounce society’s injustices. The beauty of this performance was enough. There was no need for any discourse or message. The audience simply felt better. Everything I do has meaning and logic for me. I don’t do things randomly. I don’t improvise. Nor do I desperately try to provoke people. I had a limited set of parameters, but they still allowed me to do a lot of things. If these experiences happen to create certain feelings in people, then that is something powerful…

You flipped a coin to decide whether or not to accept the Centre Pompidou’s offer to take part in Expo 72. If the coin had landed on heads, what would you have done?

I would have organized an exhibition like the ones I did in Madrid and Dusseldorf at about the same time.

No regrets about not doing the exhibition?

I was committed to this protest against the Centre Pompidou. I couldn’t protest their organization and agree to exhibit there at the same time. That exhibition, Expo 72, was supposed to represent French art with 72 artists. It was an event prepared in secret. I found out in the newspaper that François Mathey was named curator of the exhibition. But no one knew anything about it. We asked him to give us some information, but he refused immediately. It really got on my nerves because I had invested a lot of time into the exhibition: assembling the artists, telling them what we were going to do, organizing meetings, working together to think about how to change the Centre Pompidou… Protesting the exhibition worked. On the day of the opening, a group of politically active visual artists called the Front des Artistes Plasticiens distributed tracts and the curators called the CRS riot police. It was a total scandal. The Malassis coop had agreed to take part, but when they saw that the police were clubbing the artists, they backed out… Our goal was not to be destructive without a reason. We were never against the Center Pompidou. We wanted it to work differently.

How do you view the Centre Pompidou’s organization today?

Nothing’s changed. The curators make all the decisions. They decide to do themed or other exhibitions. And for the artists, it’s all random chance. Back then we sent an enormous number of suggestions to the Centre Pompidou. We suggested creating a small area managed independently by artists. Where artists could meet, imagine new things, create new dialog… But as soon as they get a little power, people cling to it.

What are you working on at the moment?

Hermès asked me to do a carré scarf. They’ve done them with other artists, like Josef Albers, Daniel Buren and Hiroshi Sugimoto. I’m doing color variations based on the ten-panel Longue Marche painting that was exhibited at the Palais de Tokyo.

You’re always wearing an ascot…

It’s to make me look classy… My father was a railway man. He operated coal-powered locomotives. To keep the coal dust out of his mouth, he always wore an ascot. And a cap, too. I remember every time he got home from work, he would wash and wash again, to get all the coal off his skin. So the ascot protects my throat. Keeps my singing voice in tune… The cap helps in winter with the cold and in summer with the sun. Sometimes it protects from light, too, when there’s too much.