OUR INTERVIEW WITH WILLIAM FORSYTHE

By Crash redaction

Photo : William is wearing a Dior Homme jacket. © Henrike Stahl

On the occasion of the William Forsythe / Hiroshi Sugimoto creation at the Opera de Paris, rediscover our meeting with the world-renown choreographer.

Artist William Forsythe has long stood as an incredible innovator in choreography, placing the body at the center of his creations and never shying away from experimentation and improvisation. By changing the rules of classical ballet while still respecting the craft, he has succeeded in inventing his own dance vocabulary made up of fast footwork and épaulement. After working for respected ballets in Germany, the choreographer created the Forsythe Company in 2005. Today, William Forsythe returns to Paris to present “Choreographic Objects,” an installation featuring two immense robots flanked by black flags, at the Gagosian Gallery in Le Bourget. These two impressive mechanisms complete the process of reflection and exploration Forsythe has undertaken into the question of individuality and the body for nearly forty years.

How did you manage to bring these huge robots to Gagosian Gallery?

These are industrial robots. We took them from the industry and made them beautiful again. In a way, we put some make-up in them. (laughs) It was mostly paint. We went from having an industrial task to having a poetic task. After the exhibition they will disappear back into an industrial landscape. Instead of taking care of other things, the robots take care of each other. They frame each other visually and almost aestheticize each other.

Almost like animals.

It has become more and more like animals. The viewers used to think about a man and a woman and I worked very hard to erase gender. Strangely enough, what came out was an association with nature which seems odd or controversial considering they are robots – the most unnatural thing possible.

Usually these kinds of robots are used to build cars.

Yes, we get them from the industry, whether it be at Mercedes or BMW. These are very popular industrial robots made by a German firm. They have a lot of articulation and six different degrees of freedom.

Do you create the movement of the robot with a computer?

No, it’s created live. We have a computer simulator, but it’s only to build ideas and not program.

The choreography is twenty-eight minutes long?

Yes, it’s a duet. It’s also acoustically composed, I am very aware of the noise it makes. It’s actually quite nice if you hear people talking, I’m not sure how it would sound at an opening event.

I would say the robots have different opportunities to have a voice, sometimes they even sing together, to use a metaphor. They share some properties but it’s all about oblique relationship. It’s three-dimensional angular differences.

Did you create this installation specifically for this space?

Yes. We had a version made for New Zealand before, but it didn’t work for this space. This one is exactly the size of the room. Also, when we first did it, three years ago, we were less skilled. Today, we understand better how the system works with the robots, the flags, and the air.

When you see this installation, don’t you want to have a dancer in it?

That’s not the point. You don’t need a human. What is interesting is that the robots are lethal, they have no brain. They just follow a program; these aren’t intelligent robots.

Is this the first time you have worked with Gagosian Gallery?

Yes, it is. It’s the first time I’ve worked with the gallery alone. I’ve been producing these objects for twenty-two years, but I’ve never worked with a commercial gallery. I must say that Gagosian functions like a really good museum. They take big risks. It’s interesting that they think choreography is worth exhibiting in this context. You can’t invite yourself to this party. The museum has acknowledged that the status of choreography has shifted.

It’s also a great space here at Le Bourget.

Oh my god, it’s fantastic! There was a Walter De Maria show here, it was so beautiful!

Have you seen the Chris Burden exhibition?

I haven’t, but I love the artist.

The Sterling Ruby show here was also amazing.

It’s a wonderful place to exhibit.

It’s really an experience, it’s more than a gallery.

It’s different than a museum, too. Museums usually don’t have this kind of space.

Why did you feel the need to produce objects like this, after working in dance?

It wasn’t something I did after. Like I said, I’ve been producing these objects for the last twenty-two years. It just started as a proposal to see if I could work without a professional body. How would the subject organize itself if we didn’t have the same medium, which is professional dancers? Professional dancers are a medium to work with. This is just another kind of medium. It’s a continuity, there’s no real break. I use the same skills as at the Paris Opera.

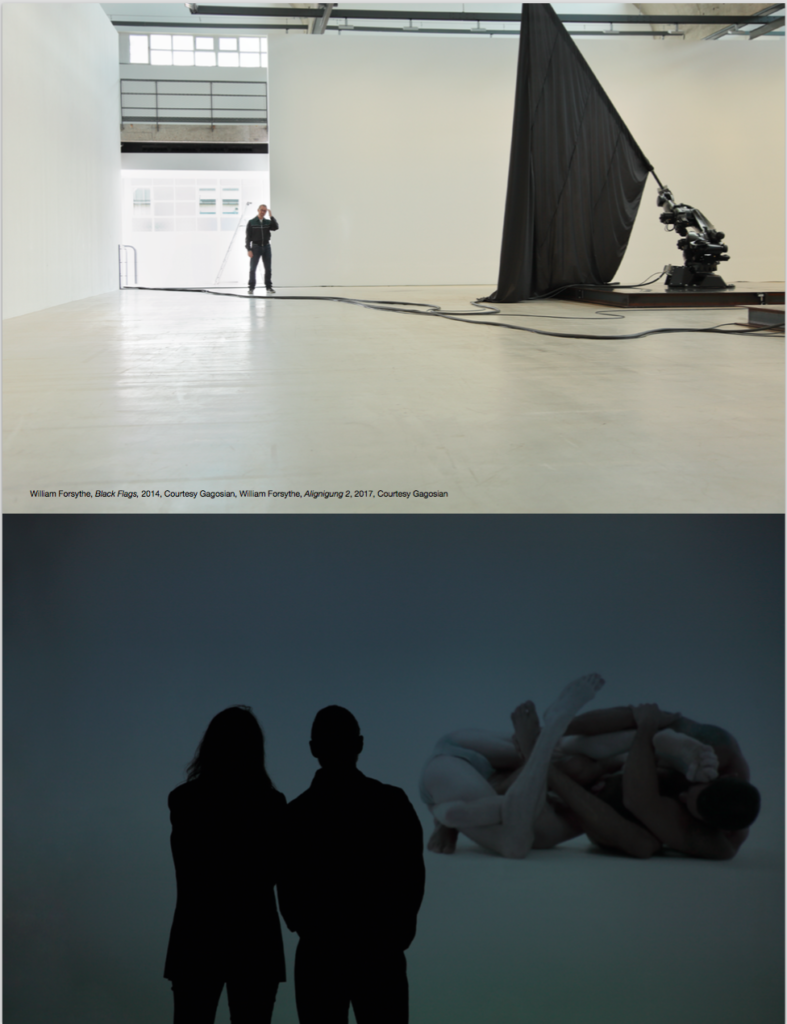

Up : William Forsythe, Black Flags, 2014, Courtesy of Gagosian, down : William Forsythe Alignigung 2, 2017, courtesy of Gagosian © Henrike Stahl

Why did you chose black flags?

First of all, they are neutral.

You think black is neutral?

In this case yes. Black gives you a lot to work with but doesn’t absolutely specify. For some, it may signify anarchy. There’s even an insect-repellent that’s called “Black Flag.” There’s a band called “Black Flag.” I’m thinking this is a signal from the future. These robots will be the dinosaurs of our future. It’s almost like a message from the future. We are speaking to our next generation and we are unsure of what our future will be like. Will the future robots destroy our way of life?

Are these robots from today?

Yes, they are state-of-the-art robots. You can’t get any better.

Do they have names?

Right and left. (laughs) They don’t have genders. We tried to get rid of all of that and I think we did a good job. They don’t feel as if they’re acting stereotypically at all.

How did you construct the robots’ choreography?

We make novels of action, like little modules. From that, we try to create a certain amount of difference, obviously. We have different ways to use the air. Each and every movement, with the exception of one, has to do with the air. I would say there are twenty different ways to use the air. It took us a long time to figure out how the tissues react and what the time of the reaction was. How long does it take to fall, how long does it take to fold, how long does it take to collapse…We build up a structure and then we find out where it fails. If it fails, it wraps around itself and it becomes immovable.

How many pieces like this exist?

It’s the only one.

What happens if you want to buy it?

You don’t necessarily have to. This is an interesting discussion we’re having. Whether one would purchase the choreography or the robots. These robots are beautiful, but they are threatening. They’re like killer whales.

Are you going to continue making robots?

It’s a medium and I think the flags were a good solution or counterpoint to the qualities of the robots which are very hard and mechanical, possessing only a kind of geometric language. Whereas the super complex technology of the flags are unpredictable to a great degree. They’re similar but never the same. It’s like the robots are wrestling with unpredictability. It’s a sculptural moment.

How do you think people will interpret this piece?

I don’t know. That’s the whole beauty of it all. You have no idea how people interpret it. Everything is open to interpretation. You can’t have an opinion about interpretation, it’s a phenomenon unto itself. People like to anthropomorphize, make things either human or sensual. It depends on how they classify action and what their references are. And, of course, people like to interpret. Human beings love to narrate. I don’t really have a narrative gene, I just see movement.

Do you consider it to be a sculpture?

No, it’s a choreographed object. There are plenty of instances of this particular kind of relationship. You can choreograph water in a fountain. It’s not an entirely new thing either, but the robots are a new medium.

I’ve never seen any robots in contemporary art.

I know someone is doing animatronics: little figures that look like humans. I’m not interested in that, I’d rather work with the human body.

Is the human body a material for you?

Absolutely, it’s a medium. Many artists use the human body, but some of us call ourselves choreographers. It’s a medium, just like painting is. In this case, these are objects that are made to move. Humans are fascinated by the idea of the animation of inanimate material. Like Jesus Christ. He’s inanimate, he died, he’s just a piece of meat. Then, he becomes animate. There are numerable examples of cultures interested in animation. Like animated puppets from early times.

Tell us about the video Aligninung, which is also displayed in the exhibition.

It’s about making optical puzzles. Using two bodies to make visual confusion. In the other room it was a human looking at two robots, in this case it’s a robot looking at two humans. The camera is on the robot and the robot moves around these people. The movement you see is all in the eye of the robot. The dancers are in another movement universe. The robot camera is at two hundred frames, so it looks as if it was frozen. But the robot is actually moving very fast. These are moments you couldn’t capture in a performance. In the video, the bodies become hybrid creatures. These are very skilled dancers.

Is it an improvisation?

Yes and no. The system is very specific, but the results are always different depending on where the starting point is. It also references some classical sculptures.

What is interesting is that in the other piece we were trying to get rid of the genders, and in this one we want to get rid of any lobotomization, trying not to make it erotic. It’s tricky.

The speed is real?

No, it’s two hundred times slower. This is what a human observer couldn’t do, while the robot can fly over like a drone. They learn to sense the complexity of their relationships. They both keep trying to erase themselves. It’s almost more sculptural than the robots.

Do you see any potential connection to performance?

They did perform it once at LACMA for two hours non-stop. But I like the idea of controlling the optical complexity. There are series of last grips with which the whole thing starts.

Can you describe the last object in the exhibition?

This is the most choreographic object to end the exhibition. This is also, like the robots, an extension for a certain class of labor who were economically disadvantaged. This was supposed to make them more efficient and work better. It’s an industrial tool for the domestic industry. This is a dinosaur and those are future dinosaurs. You have a duo: you and the object are a team.

Interview by Armelle Leturcq.

“Choreographic Objects” will take place at Gagosian from October 15th to December 22nd.

“William Forsythe x Ryoji Ikeda” takes place at La Villette during the Paris Autumn Festival, from December 1st to 31st.